In the late 18th century, Bavaria was an economically backward state, heavily relying on agriculture. Bavaria’s Elector, Karl Theodor (1777-1799), though usually more interested in arts and philosophy than in state affairs, was aware of the problems arising from a weak industrial economy – especially with the French revolutionary army roaming Europe. Karl Theodor looked to England, a prosperous nation, and the number 1 in technical innovation.

In the late 18th century, Bavaria was an economically backward state, heavily relying on agriculture. Bavaria’s Elector, Karl Theodor (1777-1799), though usually more interested in arts and philosophy than in state affairs, was aware of the problems arising from a weak industrial economy – especially with the French revolutionary army roaming Europe. Karl Theodor looked to England, a prosperous nation, and the number 1 in technical innovation.

Plotting

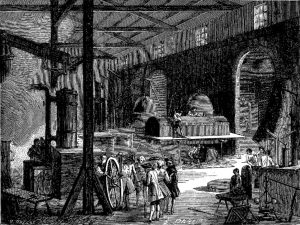

Karl Theodor – probably inspired by his consultant, the smart Count Rumford – came up with a cunning plan: He would send a gifted young man to England, and have him find out as much as possible about the nation’s latest inventions. Among the best targets for an industrial spy were James Watt and Matthew Boulton, famous for their work on steam engines. Boulton & Watt was founded in the West Midlands, near Birmingham in 1775, and grew to be a major producer of steam engines in the 19th century. To place a spy right in the heart of Boulton & Watt, Count Rumford ordered from them a machine for the city of Mannheim. He also asked that a Bavarian metalworker be allowed to come to the factory and watch the building of that machine as he would have to operate and maintain it later. Boulton & Watt agreed. At that time, it was usual to have students in the workshops. Most of them paid for the privilege to learn from a noted master. They were, however, not supposed to steal ideas.

The making of an industrial spy

The young man to spy on Boulton & Watt was Georg Reichenbach, a 20-year-old metalworker and budding instrument maker.

Georg, son of a master mechanic, and master cannon-borer, was admitted to the Military School. He received a knowledge of mathematical instruments and was inspired to try and construct similar instruments in his father’s workshop. He was talented and his work came to the attention of Count Rumford. Rumford was interested in science and specially canons, and thus had sought the acquaintance with Georg’s father. It probably was Rumford’s idea to send the young man to England.

To spy for the Bavarian Elector, Georg received a grant of 500 gulden for his journey to England in 1791, as well as an introduction to James Watt and Matthew Boulton.

With a little help from – gin

Once in England, Georg’s tasked turned out to be more difficult than expected. While he was at liberty to study the machine Count Rumford had ordered, Georg had no access to the latest inventions. These were kept secret. Among them was an improved steam machine, much more powerful than the ones Watt and Boulton had built so far – a very desirable object. To get access to this machine, Georg bribed the gate keeper of the factory with gin. Thus, he was let in at night and was able to make drawings of the machine.

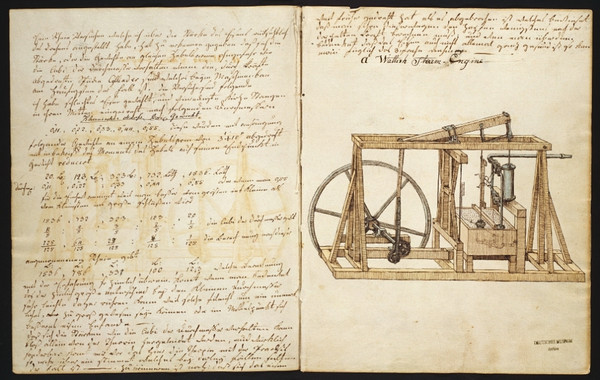

Georg left England in January 1792. His secretly made drawings are today the property of the Deutsches Museum at Munich.

Pages from Georg’s notebook with a sketch of one of Watt’s steam engines, around 1791, archive of Deutsches Museum, HS 6168

Related articles

The Poor Man’s Son Who Usurped the British Market of Optical Lenses

Your Challenge: Equip the Army with Small-Arms between 1793 and 1815

Sources

- Weber, Wolfhard, “Reichenbach, Georg von” in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 21 (2003), S. 302-304 [Online-Version]

- Ranft, Wolfgand „Dokumente im Deutschen Museum beweisen Bayern spionierte Erfinder der Dampfmaschine aus“, BILD, veröffentlicht am 02.2016

- Schneider, Ivo: „Rashomon oder Georg Reichenbach. Der geheimnisvolle Aufenthalt des späteres Ingenieurs im Jahr 1791 bei Boulton & Watt in Soho.“; in : Kultur und Technik, 2/1996

- Deutsche Museum, Museumsinsel 1, 80538 Munich, Germany