In the Georgian age, the book trade flourished in London. Reading was a popular pastime. Books were often read to friends and family for entertainment. Until the end of the 18th century, newly published books were sold without a binding. A person who bought a book received only the printed paper with temporary sewing, a so-called “board”. He/she would go on to engage a bookbinder to have it bound to match his/her personal library.

In the Georgian age, the book trade flourished in London. Reading was a popular pastime. Books were often read to friends and family for entertainment. Until the end of the 18th century, newly published books were sold without a binding. A person who bought a book received only the printed paper with temporary sewing, a so-called “board”. He/she would go on to engage a bookbinder to have it bound to match his/her personal library.

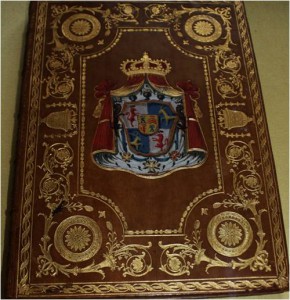

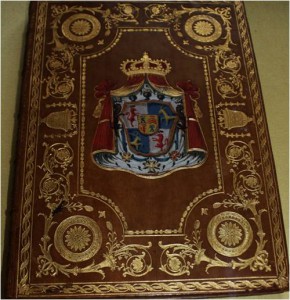

A bookbinding of high quality would find admirers in highest ranks. Wealthy aristocrats and gentry were affluent enough to order specially designed books for their libraries. Their books collections were made to impress, and so the books had to be bound befittingly. Many quality bookbinding workshops were located in Westminster, in the vicinity of the tailors. Thus, a gentleman could conveniently order a new coat and a binding for a new book in one afternoon.

Continue reading →