One of the most proficient travel writers of the late 18th century was – a woman: Mariana Starke. Her travel guides were an essential companion for British travellers to the Continent.

One of the most proficient travel writers of the late 18th century was – a woman: Mariana Starke. Her travel guides were an essential companion for British travellers to the Continent.

Being successful didn’t make life easy for Mariana. Female writing for the public was frowned upon. From her years as budding authoress to the latest edition of her successful travel guide, she always had to deal with criticism from more conventional members of society. Unperturbed by this, she led an unusual life for a woman of her time.

Mariana was born into a well-to-do merchant family in September 1762. Her mother loved reading and the theatre, and it was she who educated her children. The family was living on the fringe of the literary circle. Friends of the family included William Hayley, the famous poet, biographer and patron of artists. Hayley encouraged Mariana in her writing.

Secret life as a writer

We have to assume that Mariana was one of the persons who had always been writing. She was rapturously fond of antiquity, gothic structures, and tragedy. Being close to literary circles meant she identified with published authoresses, and she was conscious of criticism towards female authors. When in 1781 an acquaintance of her, Anne Francis, published “Poetical Translation of the Song of Solomon, from the original Hebrew” under her own name, she was talked about. Mariana wrote with mixed feelings in a letter to William Hayley:

“Our Epsom Ladies were quite astonished that (Anne Francis) should be in the least degree like other people – one observed that she really dressed her hair according to the present fashion, another, that she had a very tolerable cap, and a third that she certainly conversed in a common way, in short they spoke of her, as tho’ they had expected to have seen a wild beast instead of a rational creature, & I felt myself very happy that they were perfectly ignorant of my ever having made a Poem in my life.”

The budding talent

Despite raised eyebrows about authoresses, Mariana kept writing. Her career was kicked off with a co-translation of “Theatre of Education” by Stéphanie-Félicité de Genlis. It was published anonymous in 1787.

The budding talent then tried her hand at theatre plays. As it happens, already her first play, “The Sword of Peace”, was a major success. It was performed at no less location than the Theatre Royal in Haymarket / London in 1788. Mariana was now 26 years old. Success still didn’t mean she could put her name on her work. The play was published anonymously in 1789.

Appearing on stage in men’s cloth

When her next play, “The British Orphan”, was first performed at a private theatre in 1790 Mariana herself performed on stage. As if writing wouldn’t be shocking enough in a woman, she further endangered her reputation by appearing on stage dressed as a man. It caused a stir in more conventional circles.

In the audience was a certain Anna Larpent. Her husband, John Larpent, was the strict and careful Inspector of Plays serving as the single approver of plays that were to be performed in Britain. Anna was de facto assistant Examiner of Plays. And she was not amused at all by what she saw:

“I was shocked – I disapprove the whole. (…) – My spirits were hurt with contemplating so much folly, I could not be amused. I was sorry to see Miss Starke thus travestie (…)”.

Luckily, Mariana got away with her outrageous behaviour. “The British Orphan”, however, remained unpublished. Her next play, “Widow of Malabar” was a tragedy about an Indian widow being saved from the funeral pyre by an Englishman. The play was performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in 1791. It was a considerable success.

“Miss Starke’s play The Widow of Malabar came on and it went off extremely well – (…) (she) had a very full house”.

(Mrs Crespingy in a letter in 1791)

Travels and adventures

Mariana started travelling in 1792. She would be on the Continent with her family until 1798, despite the wars. Military conflicts could come rather close. She witnessed the first entrance of the French into Italy, resided in Tuscany when the French seized Leghorn and endeavoured to revolutionize Florence, and she was in Rome when the French overthrew the Papal Government.

In Nice in 1792, Mariana needed to get her family out of town before the city was bombarded.

‘I immediately went to the quay, with an intention of hiring an English merchantman (our nation being at peace with France), and getting my family and friends embarked before the city was bombarded, a circumstance which we hourly expected to take place; but no English vessel could I find ready for sea…’ (…)‘

Advised to make as little parade as possible on our way to the port, my family went two and two by different paths, while I, being obliged to stay to the last, walked down, dressed as a servant, passing all the French posts without the smallest molestation.‘

Adventures like these are part of her “Letters from Italy”, published in 1800. Adventures also shaped her list of equipment useful for travellers. These included:

- a mosquito-net

- a travelling chamber-lock

- pistols

- a pocket-knife to eat with

- a medicine chest (including i.a. pure opium and liquid laudanum)

- a strong English carriage, with strong wheels and a sword case. The blinds should be made to bolt securely within-side, and doors to lock

Travel writing became her new passion. She travelled to the Continent from 1817 – 1819, 1824 – 1825, and 1827 – 1830.

Mariana was the first travel writer to recognise that the majority of her readers would be travelling on a budget and with their family. She therefore included a wealth of useful advice on luggage, obtaining passports, the precise cost of food and accommodation in each city and she even added advice on the care of invalid family members. She also devised a system of exclamation mark ratings, a forerunner of today’s stars. Famous and influential John Murray became her publisher. Mariana’s guides became the prototype for Murray’s own travel handbooks.

Nevertheless, male reviewers often sneered at Marian’s lack of formal classical education, and mocked her practical advice such as what prices to pay for washing clothes in Rome, where to by medicine in Paris or what to do against bugs or flees in hostels. For them, a travel guide written by a woman was too emotional, tended to be poetic, lacked a system of systematization, and was, all in all, too effeminate. These men preferred a guidebook based on masculine objective authority. It ended up in the Baedeker, a guide bare of emotion, adventure – and individual experience, while Mariana’s work was belittled.

Becoming the proto-feminist of travel writing

Mariana was fond of the Continent, and especially of Italy. It was important for her to note that these foreign countries weren’t especially dangerous, neither for male nor for female travellers. Highway robberies were quite uncommon on the Continent, she assures her readers:

English Travellers … have rarely been robbed; unless owing to imprudence on their own part, or on that of their attendants.

(Mariana Starke)

By doing so, she influenced many female tourists to go abroad and see the world. Magazines such as Belle Assemblée reviewed Mariana’s latest guidebook in 1833 and concluded:

We request therefore that all nervous ladies and timid maids discard their fears of finding a blood-drinking brigand under the lee of every rock, and a murderous gun behind every bush; and advise that if this dread was all that impeded their journey, to set of instantly with Mrs. Starke’s travelling guide in their carriages.

Thus, Mariana is today regarded in the light of a proto-feminist of travel writing.

Sources

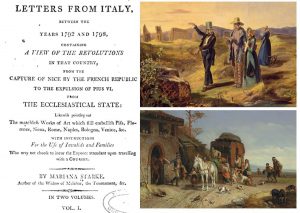

- Mariana Starke: Letters from Italy: between the years 1792 and 1798, containing a view of the revolutions in that country, from the capture of Nice by the French republic to the expulsion of Pius VI. from the ecclesiastical state; likewise pointing out the matchless works of art which still embellish Pisa, Florence, Siena, Rome, Naples, Bologna, Venice, &c. With instructions for the use of invalids and families;R. Phillips, London: 1800 (https://books.google.de/books?id=byE518MhWnsC&printsec=frontcover&hl=de&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false)

- Dr Benjamin Colbert: British Travel Writing: Mariana Starke; The British Academy, Centre for Transnational and Transcultural Research, University of Wolverhampton

- Elizabeth Crawford: Mariana Starke; https://womanandhersphere.com

- Rebecca Butler: Can any one fancy travellers without Murray’s universal red books’? Mariana Starke, John Murray and 1830s’ Guidebook Culture; The Yearbook of English Studies, Vol. 48, Writing in the Age of William IV (2018), pp. 148-170 (23 pages), published by: Modern Humanities Research Association

Related articles

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)