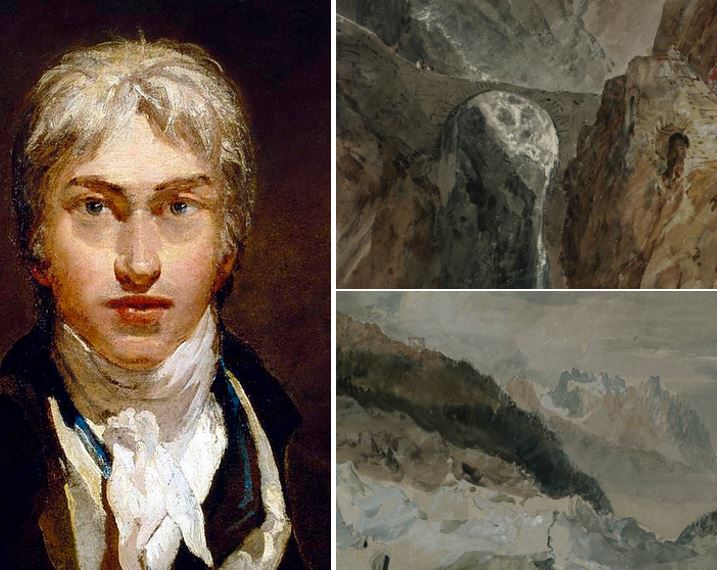

Around the turn of the 19th century, Joseph Mallord William Turner was a young, restless painter, always on the lookout for inspiration for his art. After having toured many parts of Britain, he planned to visit the Continent. He was especially interested in the awe-inspiring, romantic Swiss Alps – considered by many a rocky, dangerous wasteland. Thus, aged about 27, and still being an unknown artist, he decided to follow his plans through. Let’s accompany him on his first ever trip abroad.

When to go

How to get to Switzerland while the Napoleonic Wars were going on? Private

travels where hardly possible. It was only with the peace treaty of Amiens at

the end of March in 1802 that the political climate allowed again the

opportunity for travelling.

The climate in Switzerland was another matter to consider. In the Alps, the

roads were bad, and blocked by snow and ice for many months. Going there in

April wasn´t an option. Therefore, Turner made his first trip to the Continent

in the summer of 1802.

Legitimation and Finance

Until Turner could start, there were many organisational things to do. Among them:

- How to get enough money?

- How to get a passport ?

Though Turner was still far away from being a famous artist, his talent for painting was recognized by influential circles of the London art scene. They agreed that his skills and his career would benefit from a trip to Paris, in order to study the paintings in the Louvre. Financial sponsors were thus the Earl of Darlington, the Duke of Bridgewater and Walter Fawkes, a Yorkshire landowner and Turner’s earliest patron. Most helpful however, was Mr. Newbey Lowson, a young country gentleman with antiquarian and artistic interests from Darlington Durham. He travelled together with Turner, and Turner gave him drawing lessons en route. All in all, Lowson financed the main part of the tour to Switzerland.

Support for his travel plans was also offered by Lord Yarborough. He had known Turner for some years and stood as a referee for Turner’s passport.

During the 18th century, British passports were mainly for diplomats, officials or professionals such as merchants. Tourists were still rare, and only the affluent traveller were able to obtain a passport. The document cost about 6 pounds, 7 shillings and 6 pence in 1778.

Travel information

Turner was plotting his sketching trips with the precision of a military campaigner. However, information on Switzerland was hard to get.

- The first handbook for travellers to this country was yet to be invented (being Murray’s Handbook For Travellers In Switzerland, published in 1838. It is believed that Turner used it on his later Alpine tours).

- A travel account in English existed. It was “Travels in Switzerland, and in the country of Grisons : in a series of letters to William Melmoth, Esq. from William Coxe”. It comprised the travel experiences from the year 1779 to 1787, and was published in 1789. It deals however, more with history and political administration than with practical tips for travellers.

It was thus best to hire a trustworthy local guide. In 1802, Turner and Lowson hired a Swiss servant and guide for five livres a day. From the pay, the man had to cover his own expenses.

Basic knowledge for travellers to Switzerland

- In 1802, the country had been

under Napoleonic rule since 1798. It was named République Helvétique. The

confederate Diet was replaced by a bicameral parliament of indirectly elected

members and a five-man directory, which functioned as the government.

Although the government was in Swiss hands, the country was obliged to accept a number of unpopular measures imposed by the French. These included accommodating and feeding French troops and allowing them to use Switzerland as a transit route. Switzerland was also obliged to accept a treaty of alliance with France, breaking the tradition of neutrality. - It was ‘a very troubled state’, as Turner noted. The cantons were distrustful of each other. Almost every canton had a coinage of its own which was not accepted in the next. Most towns, however, accepted French Francs as payment.

- Distances were reckoned not by miles, but by stunden (hours, i.e. hours’ walking) or leagues. The length of the stunde has been calculated at 5278 metres.

- The people were ‘well inclined’ towards the British

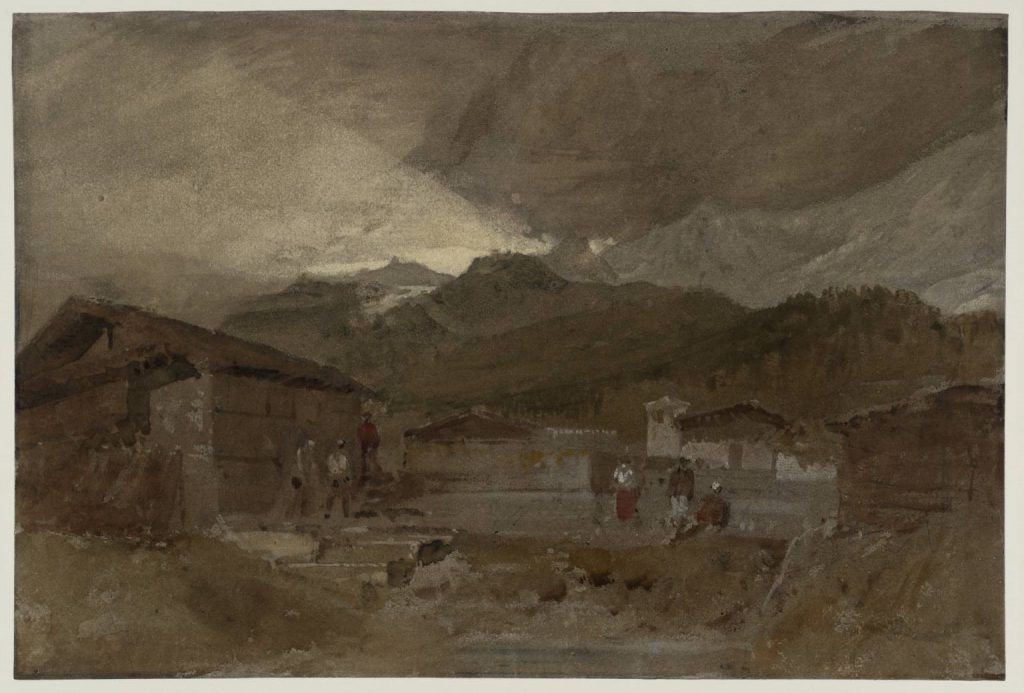

One of the groups of three figures sketched here might be Turner himself, his travelling companion Newbey Lowson and their guide.

Where to stay

Tourism, now a main business in Switzerland, was in the very beginning at Turner’s time. Accommodation in the Alpine region was poor. Travellers often stay in hospices, cloisters or very simple inns.

It’s only on his later trips, in the 1840ies, that Turner could profit from the rise in tourism (that he himself had helped to start). Then, he often stayed in ‘Restaurant Schwanen’ (“The Swan Inn”) in Lucerne. It offered board and rooms, and the views over famous Mount Rigi.

In Zurich, Turner – on his later trips – might have stayed in a hotel called ‘Schwerdt’ (“sword”). It was mentioned in Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland, though the handbook rather warned against it than recommended it.

Being out and about

A trip to the Continent started, of course, by boat. In 1802, the political climate in France might have been mild– the weather in Calais often was not. Turner suffered a stormy landing, and in the end had to wade ashore through the breakers. He continued to Paris, but not to study the architecture of the city or the works in the Louvre.

To Turner and Lowson, Paris was but a place for travelling preparations (Turner would return there at the end of the trip and dutifully make sketches in the Louvre). The two men bought a small carriage (32 guineas). The carriage was a luxury indeed: Of course, it made travelling faster, smarter and saver than going on foot. It also enabled Turner to carry larger and bulkier sketchbooks than would have been practical otherwise. He took his chances and bought additional sketchbooks in Paris.

The men set off, going via Lyon and Grenoble to the Grande Chartreuse, a monastery in a lonely mountain region in the Isère department. Turner described the area as ‘abounding with romantic matter’. From here they moved on to Geneva, but only for a pause. The gateway to the Alps, Bonneville, was yet to come. And so was the real adventure.

Hard climbing

The Alpine mountains were often not accessible by a carriage. Turner and Lowson frequently had to send their vehicle ahead, while they continued on foot. They did so, e.g., from Bonneville to Mont Blanc, and down the Val Veni to Courmayeur and the Val d’Aosta. It was a hard tour. And more was to come, from Aosta over the Great Saint Bernard Pass. The ‘road & accommodations’ are ‘very bad’ Turner noted.

Thursday, 25. Heavy rain. Turner went out to sketch.

(Diary of Maria Sophia Fawkes, 1816)

They continued north to Lake Geneva past the castle of Chillon to Lausanne, and Berne. As glaciers, forests and looming mountains had captured Turner’s fascination, Turner topped up his supply of sketchbooks in Berne.

Blair’s hut – also called ‘Château de Blair’ – was built in 1779 by Charles Blair, an Englishman living in Geneva. The hut commanded a view of the Mer de Glace. Turner and Lowson went there with their guide. Turner climbed down to the glacier to make his drawing. The finished watercolour painting was later owned by Walter Fawkes, Turners patron.

Alternative transportation

To explore the scenery around the Reichenbach Falls Turner and Lowson hired mules. A day’s trip by boat along Lake Brienz allowed them to sketch the ruined castle of Ringgenberg. Finally, they arrived at Lucerne, a town Turner would revisit often. Here, on a boat tour of the lake, he had his first sight of the Rigi mountain. The Rigi fascinated him; it would be among his favourite subjects on later travels to Switzerland between 1837 and 1844.

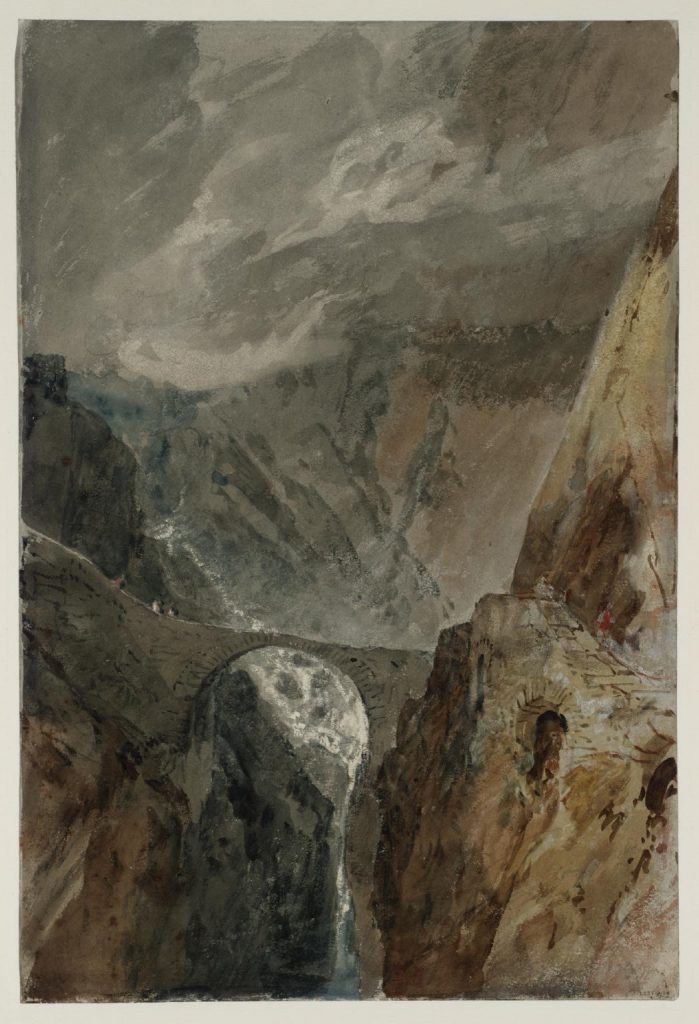

The highlight of his mountain tours was a trip into the St Gotthard Pass. It was exhausting. Besides, the Devil’s Bridge, rebuilt near the top of St. Gotthard pass, was one of the most frightening passages in the world. It was only from 1834 that carriages run regularly via the St Gotthard Pass. But Turner didn’t mind the strain. It had its advantages over travelling speedily as he did later in the century:

I am fortunate to have met a funny, small, elderly gentleman who will probably be my travelling companion throughout this trip. He constantly pops his head out of the window to sketch whatever catches his fancy. He becomes quite angry when the coachman refuses to wait. He seems to be an artist. (…) Maybe you know him. The name on his luggage is J.W. or J.M.W. Turner.

(from the letter of a young Englishman travelling for business reasons from Rome to Bologna in 1829)

The Devil’s Bridge, rebuilt near the top of St. Gotthard pass, was one of the most frightening passages in the world.

What to eat and drink

Famous Swiss fondue – melted cheese with bread cubes – was actually invented at the end of the 17th century by Alpine herdsmen. Other food and drink would include wine and beer, chestnuts, potatoes, and sausages such as beef, smoked pork and beef tongue, smoked pork, pigs ears or tails cooked with juniper-spiced sauerkraut, pickled turnips, and beans.

Watch a video here how to make an 18th century mint sandwich from Switzerland

What to see

Looking back on several months of sketching and hiking in Switzerland, Turner remembered:

‘The Grand Chartreuse is fine; – so is Grindelwald… The trees in Switzerland are bad for a painter, – fragments and precipices very romantic, and strikingly grand. The country on the whole surpasses Wales, and Scotland, too… ()

Turner was to return to Switzerland from 1837 to 1844 and spent the summers exploring the length and breadth of the Alps.

There’s a sketch at every turn.

(JMW Turner)

Aftermath of the alpine experience

Turner’s tour of the Alps was the formative experience of his life. It also provided him with material for years to come.

Hawkey – Hawkey [Mr. Fawkes, Turner’s patron] – come here – come here! Look at this thunderstorm! Isn’t it grand? – Isn’t it wonderful? – Isn’t it sublime?.. There, Hawkey; in two years you will see this again, and call it ‘Hannibal Crossing the Alps’.

(JMW Turner, around 1810)

Inspired not least by Turner’s paintings, Switzerland became a popular travel destination for British tourist wanting to experiences the awe, terror and danger of nature themselves.

Related articles

Sources

Sublime Sites; Explorations in the footsteps of Turner, Cotman and Ruskin with Professor David Hill (https://sublimesites.co/ )

Museum of Art Lucerne, Exhibition „Turner, Luzern und die Alpen“, https://www.turner2019.ch/

David Blayney Brown, J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, The Tate, January 2010

Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland, John Murray, London, 1838

Jeannie Phan / Culture Trip: 6 Ways To Walk in the Footsteps of William Turner in Lucerne (https://theculturetrip.com/europe/switzerland/articles/six-ways-to-walk-in-the-footsteps-of-william-turner-in-lucerne/ )

https://beruhmte-zitate.de/autoren/william-turner/

Prue Bishop and John Lumby Bishop: The journey of JMW Turner (1775–1851) through the Chartreuse Massif in the summer of 1802; The British Art Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Summer 2015), pp. 27-42 (16 pages), Published by: British Art Journal

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)