In this post:

– Ravenna and the poetry of politics

– Plotting insurrection: the tight situation in Italy

– Murder!

– Byron and the secret society of the Carbonari

– Under surveillance and attack

Lord Byron (1788 – 1824), a man of scandals, had by 1815 crowned his wild life with a stormy affair with Lady Caroline Lamb, and a breakup with his wife. He left England to travel the Continent. True to the verdict ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know´’, he didn’t led a virtuous life there. In December 1819, he arrived in Ravenna, Italy, where he took up residence to be near his mistress Teresa Guiccioli, a married woman. There was more scandal and adventure to come: Byron became involved in the national movement in Italy – meaning secret societies plotting insurrection against the Austrian und clerical rulers. Indeed it was in Ravenna that Byron found his calling in serious political activities.

Ravenna and the poetry of politics

Despite his literary success, Byron had been dissatisfied with his life so far. He noted in his journal:

”To-morrow is my birth-day – that is to say, at twelve o’clock, midnight, i.e. in twelve minutes, I shall have completed thirty and three years of age!!! – and I go to my bed with a heaviness of heart at having lived so long, and to so little purpose.“ (21.01.1821)

However, his stay in Ravenna would give Byron’s life a new direction. Though the town was off the beaten track for British tourists, and the few travellers who made their way to it thought the natives to be anything from insipid to barbaric, Byron liked Ravenna and its people. The upper classes were educated and liberal, and he appreciated that the citizens had preserved many old traditions. To him, they were more authentic than natives anywhere else in Italy. Their passions at once impressed and amused him. He wrote in a letter:

“They make love a good deal – and assassinate a little.”

Byron soon became accepted by the Ravenna society, and also by the relatives of his mistress, Teresa. Actually, it was due to Teresa’s father and brother, Ruggero and Pietro Gamba, that Byron became involved in local revolutionary politics. He approved of their idea of a liberated Italy. He noted in his journal on 16.2.1821:

“It’s a grand object, the very poetry of politics. Only think – a free Italy!!!”

At the Congress of Vienna, Italy was assigend to King Ferdinand of Naples, The Pope and the Austrians.

Plotting insurrection: the tight situation in Italy

During the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon had conquered Milan, Ravenna and several other papal territories. After the Congress of Vienna, Italy was partly under the rule of the Pope (e.g. Ravenna), the Austrians, and King Ferdinand of Naples (Sicily and Naples). A revolution to liberate Italy from foreign rule had been in the air in Ravenna in April 1820. Byron had expected a rising then, as children were singing revolutionary songs in the streets, and rebels had written slogans such as “Up with the republic” and “Death to the pope” on the city walls. The police was on alert.

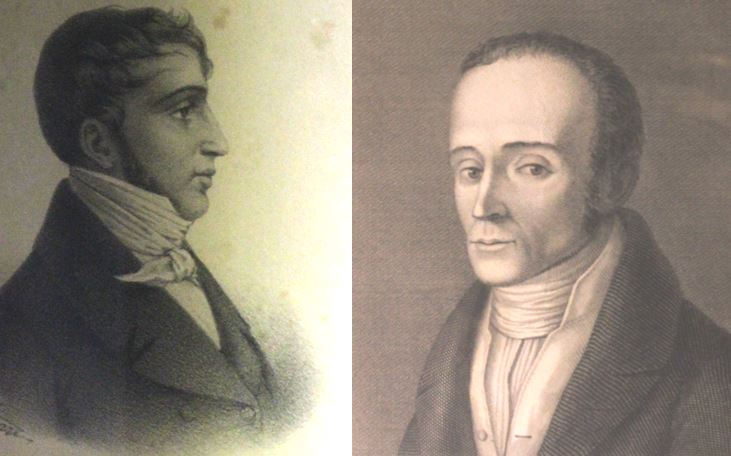

Federico Confaloniere (left) was one of the instigators and organisers of the 1821 Carbonari uprisings in Lombardy; Silvia Pellico (right), affiliated to the Carbonari, was the chief editor of an anti-Austrian Milanese journal. He was arrested in 1820.

The situation became even tighter when In August 1820 King Ferdinand was dethroned by revolutionaries. At that time, many Italians hoped the spark of revolution would move on to the north. A number of political assassinations in the Romagna occurred, and an uprising was indeed plotted for September by the so called Carbonari, a secret group of freedom fighters. But the Austrians had no intention of letting the Neapolitan revolution – or any revolution in Italy – succeed. They came to the rescue of King Ferdinand in Naples. The spark of revolution was put out, and when the army of Austria, comprising 70.000 soldiers, arrived at the border with Lombardy, the uprising plotted for the Romagna area in September 1820 dwindled away to nothing. But the underworld kept being active. Even Byron became entangled in a related assassination in December 1820.

Murder!

“I open my letter to tell you a fact which will show the state of this country better than I can. The commandant of the troops is now lying dead in my house.”

(Byron in a letter, 9.12.1820)

What had happened? The Military Commander of Ravenna, Captain Luigi Dal Pinto, was shot in the street at 8 o’clock in the evening of December 7, 1820, just 200 paces from the Palazzo Guiccioli, where Byron lived. Byron had been dressing himself to go out, and when he heard the shot, he called his most trusted servant and went out with him in the street. Captain Luigi Dal Pinto was dying, with a wound in his heart, two in the stomach, one each in a finger and his arm.

“Some soldiers cocked their guns, and wanted to hinder me from passing. However, we passed, and I found Diego, the adjutant, crying over him like a child – a surgeon, who said nothing of his profession – a priest, sobbing a frightened prayer – and the commandant, all this time, on his back, on the hard, cold pavement, without light or assistance, or anything around him but confusion and dismay.” (Byron in a letter, 9.12.1820)

Byron ordered his servant to bring the dying man into the house, and the guard to be called. Captain Luigi Dal Pinto was dead by the time he was laid on a bed. Byron and the surgeon carried out a post-mortem.

“Poor fellow! He was a brave officer, but had made himself much disliked by the people. I knew him personally, and had met with him often at conversazioni and elsewhere. My house is full of soldiers, dragoons, doctors, priests, and all kinds of persons, – though I have now cleared it, and clapt sentinels at the doors. To-morrow the body is to be moved. The town is in great confusion, as you may suppose.” (Byron in a letter, 9.12.1820)

The gun with which the shots were fired had been found on the pavement, near to the scene of the murder. The murderer was never tracked down. The police seemed to be very lax in pursuing the murder. Byron came to believe that Captain Luigi Dal Pinto had been a double agent, and a member of the Carbonari himself, but too powerful to be arrested by authorities.

Byron and the Carbonari

The fight for freedom was more than a romantic idea for Byron. Probably by introduction by the Gambas, he had joined the Carbonari, a clandestine revolutionary society, in August or September 1820.

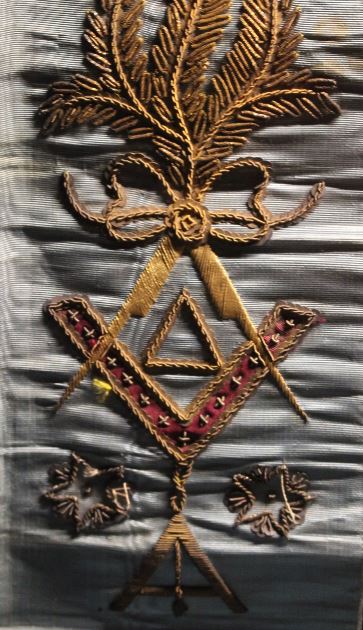

The Carbonari were secret freedom fighters, a network of insurrectionist groups. About 15.000 persons were enrolled in the Romagna branches of the Carbonari. Their members came from all social classes: nobles, merchants, craftsmen, professional adventures, semi-criminals. The Carbonari had historic links with freemasonry, were obsessively secretive and had a stress on ritual and high spiritual values. The initiation ceremony included the ceremonial passage of the blindfolded candidate round the chamber of the lodge, an interrogation by the Grand Master, purification by water, taking an oath, and the handling of secret signs.

We don’t know if Byron underwent this ceremony or not, but he knew the secret code words:

“The Count P.G. this evening (by commission from the Carbonari) transmitted to me the new words for the next six month: *** and ***. The new sacred word is *** – the reply *** – the rejoinder ***. The former word (now changed) was ***.“

(entry in Byron’s journal, 30.1.1821)

In Ravenna, the Carbonari held secret meetings at the village of Filetto, in a pine forest. Byron was invited by a group called Cacciatori Americani, a sub-branch of the Carbonari, to join their meetings in the forest:

“The Americani give a dinner in the Forest in a few days, and have invited me, as one of the Carbonari. It is to be in the Forest of Boccacio’s and Dryden’s ‘Huntsman’s Ghost’, and even if I had not the same political feelings (…) I would go as a poet, or, at least, as a lover of poetry. I shall expect to see the spectre of ‘Ostasio degli Onesti’ come ‘thundering for his prey’ in the midst of the festival. At any rate, wether he does so or no, I will get as tipsy and patriotic as possible.” (entry in Byron’s journal, 20.2.1821)

Eventually, Byron was made captain of the Cacciatori Americani. The troop comprised several thousand persons. It was an honorary title, as Byron never trained the troops. However, he bought them guns, and he also provided a safe house for several members to have consultations. Generally, Byron was willing to become active for the cause. When a stroke by the Austrians against the Carbonari was expected, he noted in his journal:

“I will do what I can in the way of combat, though a little out of exercise.

The cause is a good one.” (7.1.1821)

Mingling with revolutionaries wasn’t exactly easy, as the following episode shows:

“Last night Il Conte P. G. sent a man with a bag full of bayonets, some muskets, and some hundreds of cartridges to my house, without aprizing me, though I had seen him not half an hour before. About ten days ago, when there was to be a rising here, the Liberals and my brethren Ci asked me to purchase some arms for a certain few of our ragamuffins. So I did immediately and ordered ammuntion, &c. and they were armed accordingly. Well, the rising is prevented by the Barbarians marching a week sooner than appointed; and an order is issued, and in force by the Government, that all persons having arms concealed, &c. &c. shall be liable to &c. &c. – and what do my friends, the patriots, do after two days afterwards? Why, they throw back upon my hands, and into my house, there very arms (without a word of warning previously) with which I had furnished them at their own request, and at my own peril and expense.

It was lucky that Lega (Byron’s Italian secretary) was at home to receive them. If any of the servcants had (except Tita and F. and Lega) they would have betrayed it immediately. In the meantime, if they are denounced or discovered, I shall be in a scrape.” (entry to the journal, around 18.2.1821)

This occurrence probably stressed Byron’s occasional frustration with his fellow Carbonari, such as he had already noted in his journal on 26.1.1821:

“It is a difficult part to play amongst such a set of assassins and blockheads.”

Under surveillance and attack

Byron’s activities didn’t go unnoticed. He was under a closer surveillance by the local police. His letters were intercepted and read. Byron was aware of this:

“Letters opened? Too be sure they are” (he wrote in a letter), “and that’s the reason why I always put in my opinion of the German Austrian scoundrels. There is not an Italian who loathes them more than I do; and whatever I could do to scour Italy and the earth of their infamous oppression would be done con amore.”

Italian authorities regarded him as a dangerous and subversive presence who associated with bad characters, sympathised with revolutionary ideas and handed out money ‘in order to create a following’.

“It is thus claimed, that there are in Ravenna some ill-disposed persons, who are supported by Lord Byron, who is at this time settled in the house of the Cavaliere Guiccioli, who, it is said, has secret relations with Romagnola and with Bologna; the Fair at Lugo will be for them a signal for a combined revolt, and there will be at that time occur in Ravenna a take-over of the public places and private houses (…)“

(From the State Archives of Ferrara, 2.9.1820)

“Englishmen with radical principles such as those Lord Byron maintains, and such as those known to be held by the Lords Kinnaird and Hamilton, are to be regarded as dangerous apostles of independence and revolution, and should, without fear of complaints from the English government on the grounds of intolerance towards her subjects, be kept off the peninsula by joint procedures of all the Italian governments.”

(Josef von Sedlnitzky (head of police and censorship under Metternich) to Emperor Franz, 25.12.1825)

The authorities indeed tried to frighten Byron.

“They believed, and still believe here, or affect to believe it, that the whole plan and project of rising was settled by me, and the means furnished, &c. &c. All this was more fomented by the barbarian agents, who are numerous here (….). They put up a paper about three month ago, denouncing me as the Chief of the Liberals, and stirring up people to assassinate me. But this shall never silence nor bully my opinion.” (Byron in a letter, 25. May 1821)

Byron left Ravenna later in 1821 and went on to Pisa and Genoa. In 1823 he continued his political actives in Greece.

Related posts

- Writer’s Travel Guide: The British Tourist and Napoleonic Milan

- Queen Caroline’s Scandals in Italy

- Your Challenge: Equip the Army with Small-Arms between 1793 and 1815

- Eleonore Wickham: The Master Spy’s Wife

- Gossip Guide to the Kingdom of Naples: Inside the Palace of Caserta

- Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 2)

- Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 1)

- Travelling in the 18th century? Don’t forget your passport!

- Attractive, Distinctive, One Size: The Military Uniform in the Late 18th Century

- Writer’s Travel Guide: The Jersey Connection

Source

- A. Schmidt: Byron and the Rhetoric of Italian Nationalism; Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

- Richard Lansdown: “Byron and the Carbonari”, in History Today May 1991, p. 18-25.

- Fiona MacCarthy: Byron Life and Legend; John Murray, 2014

- Peter Cochran: Byron and Italy; Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011

- Thomas Moore: The life of Lord Byron; J. Murray, 1844

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)