The concept of the passport is thousands of years old. King Henry V of England is credited with having invented what can be considered the first passport in the modern sense. These letters of “safe conduct” were first written in Latin and English. In 1772, the government decided to use French, the international language of high finance and diplomacy. This didn’t change until 1858. Thus, Britain’s passports were issued in French even when Britain fought Napoleon.

The concept of the passport is thousands of years old. King Henry V of England is credited with having invented what can be considered the first passport in the modern sense. These letters of “safe conduct” were first written in Latin and English. In 1772, the government decided to use French, the international language of high finance and diplomacy. This didn’t change until 1858. Thus, Britain’s passports were issued in French even when Britain fought Napoleon.

What did the document look like?

For 100 of years standards for passports didn’t exist. They might be “safe conducts” as well as semiformal letters of introduction – or anything between.

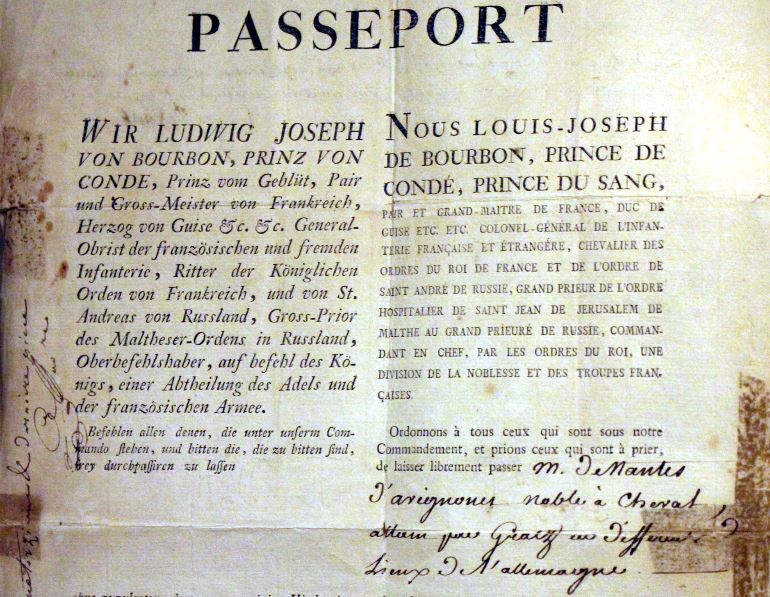

In the 18th century a passport was a single page of paper. Nobody was thinking of the durability of such a document, which was often several times folded and placed in a jacket or a leather wallet. The only security feature was a watermark and a seal. A passport did not contain a description of the passport holder or a date of birth.

A passport held by Casanova in 1758 allowed him to “pass freely to the Netherlands by land or by sea for fifteen days“. This was a “safe conduct’ enabline Casanova to enter a country during wartime.

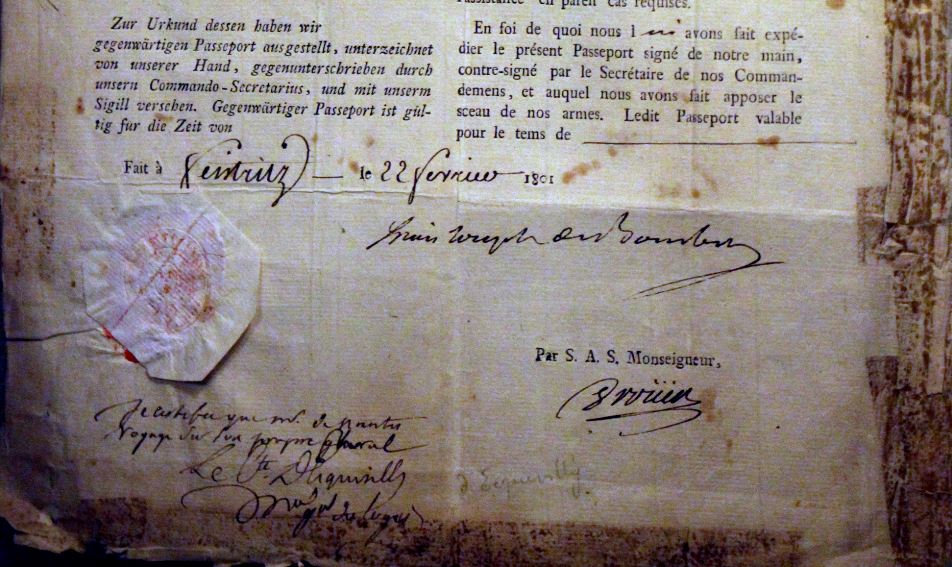

Above and below: Passport in the name of the Prince de Condé for M. de Mantes from Avignon, going to Graz and passing different places in Germany. Signed on 22 February 1801.

Who could obtain a passport – and who needed one?

During the 18th century, British passports were mainly for diplomats, officials or professionals such as merchants. Tourists were still rare, and only the affluent traveller were able to obtain a passport. The document cost about 6 pounds, 7 shillings and 6 pence in 1778.

Granting travel documents to British citizens was one of the tasks of the Privy Council of England from 1540 to the late 18th century. In 1794, issuing British passports became the job of the Office of the Secretary of State.

Most foreigners entering Britain had to obtain a passport. From the beginning of the war with France in 1793, it became necessary for these foreigners to acquire a new passport when changing the place or the usual residence. This new passport was issued by the mayor of a town. Foreign merchants were excluded. They had full liberties to pass and repass within the country.

In France, in the past, citizens had to show an internal passport to change from city to city. From 1795 all persons traveling outside the limits of their canton were required to possess either an internal passport (for voyages within France) or external passport (for travel outside France). In 1815 an internal passport cost 2 francs. Passports for foreign travel cost 10 francs. To obtain an internal passport a certificate of good behaviour was required.

Passports and travelling

We, John Earl Russel, Viscount Amberley, a Peer of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, a Member of Her Britannic Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council, Mer majesty’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, requests and requires in the name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow Mrs Elizabeth Gaskell (British subject) accompanied by four daughters travelling un the Continent with a maid servant, to pass freely without let or hindrance and to afford then every assistance and protection of which them may stand in need.

When travelling on the Continent, British tourists were examined at many control points. Cities were walled with military posts guarding the gates. Travellers had to stop, identify themselves and declare the purpose of their travel. Holding a passport didn’t guaranty easy passing of control points. Often, British passports were well respected and the passport holders considered a person of consequence. However, passport holders might discover that further documentation was required to facilitate travel to another point of the journey.

What was needed for entering a country varied across Europe. One of the strictest countries was the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily. For entering the kingdom, travellers needed a passport issued by the Neapolitan Ambassador in Rome. For other countries, passports could be obtained from Foreign ministers or ambassadors on duty in the country of the traveller.

Interestingly, when passports were lost while travelling, obtaining a new passport was usually possible without satisfactory documentation, and right in the area where the traveller found himself without passport.

Related articles

Gossip Guide to the Kingdom of Naples: Inside the Palace of Caserta

Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 1)

Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 2)

Writer’s Travel Guide: The British Tourist and Napoleonic Milan

Writer’s Travel Guide: The Jersey Connection

Beautiful Carriages from the Napoleonic Era

Captain Stanhope’s Invention: A Carriage for ‘The Ton’

Queen Caroline’s Scandals in Italy

Sources

- Musée L’Emperie, Montée du Puech, 13300 Salon-de-Provence, France

- Elizabeth Gaskell’s House, 84 Plymouth Grove, Manchester M13 9LW, UK

- Paul Simpson: A short history of passports, Wanderlust Travel MagazineTom Topol: Take a tour of historical passport collecting, Antique Trader News | November 2, 2017

- John Torpey: The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State, Cambridge University Press; 2000

- Jane Doulman / David Lee: Every Assistance and Protection: A History of the Australian Passport, The Federation Press, 2008

- Jeremy Black: The British and the Grand Tour, The History Press; 2003

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)