and in 1806 (right).

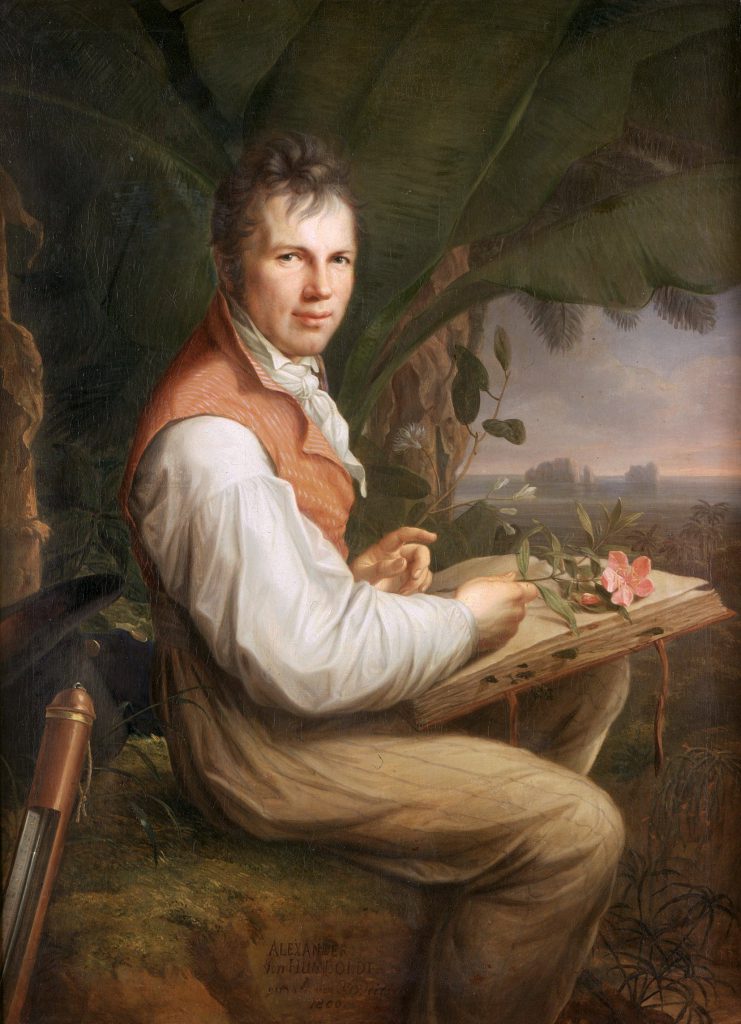

Alexander von Humboldt (1769 – 1859) was the celebrated explorer of his generation. It is little known that he started his scientific career with a trip to England in 1790. He was 20 years old, and travelled with the famous Georg Forster, author of “A Voyage Round the World”, member of the Royal Society and of Captain James Cook’s crew on the second voyage (1772-1775).

The experienced explorer and the young men had met in 1789 in Mainz / Germany. Alexander was fascinated by the lively and powerful Forster, his impressive career and exiting plans. He dedicated his first scientific thesis about mineralogical observations on basalts to Forster.

It is no surprise that Alexander was delighted when Forster, recognizing the budding talent, asked the young man to join him on his next trip in 1790. Destination: England.

Find out how the journey to England influenced the life of Alexander von Humboldt.

Financing and Planing the Educational Journey of a Young Gentlemen

Forster’s trip to England wasn’t a sponsored mission by the state. Forster could command a convenient income derived from his position as head librarian of the University of Mainz. His young travel companion came from a wealthy and noble family. The adventure was thus privately financed, and the travellers were free to follow their own agendas.

For Forster, who recently had had his plans to join an expedition to Asia shattered by the Russo-Turkish war, the trip to England was a kind of consolation. He would rediscover England (where he had not been for 12 long years), buy new books, find financial support for a new publication and try to receive some of the promised rewards of the voyage with Cook. He would also turn his travel experiences into a new book. Besides, he would introduce Alexander to his scientific community.

For Alexander, everything would be new: He would cross the sea for the first time, and he would try his hand in measuring, observing and recording. In 1790 his career path was not yet decided. His mother had high ambitions for him. She had hired the best tutors and sent her children to the best universities. Alexander had studied at the Universities of Frankfurt-on-Oder and Goettingen. His fellow-students had been the Duke of Cumberland and the Duke of Sussex. His mother expected him to become a civil servant of the Prussian state. Alexander seemed to seriously consider it: Many of the entries in his travel dairy from England focused on economic aspects and improvements. Stylish travel writing was not yet an option for him. It was left to the far more experienced Forster (who became known as the founder of modern travel literature) to put their experiences into words and in a chronological record.

The trip to England was scheduled from April to June 1790. Forster and Alexander started from Mainz on a long journey through the Southern Netherlands and the United Provinces. In England, London was their first stop. They would continue (among others) to Bath, Bristol, Birmingham, Derbyshire, Chatsworth, Stratford, Blenheim Palace and Oxford.

Alexander’s Scientific Agenda in London

Politics & Culture

On Forster’s coat-tails Alexander acquainted himself with the political life in London, and listened to speeches by Burke, Pitt, Fox and Sheridan. He attended concerts and theatre plays to form his cultural taste.

It is very likely that he visited Sir Ashton Liver’s Museum. The museum is mentioned in detail in the travel description by Forster.

Sir Ashton Liver’s Museum held the impressive collection of Charles Townley, a wealthy country gentleman and antiquary. He had travelled on three Grand Tours to Italy, buying antique sculpture, vases, coins, manuscripts and paintings. Among the most important pieces were the Townley Marbles, a collection of Greek and Roman sculptures. The collection was housed in Park Street, in the West End of London. The Townley Marbles were the most important collection in England before it became overshadowed by the Elgin Marbles.

Sir Ashton Liver’s Museum closed with its owner death in 1805. Today it constitutes the Townley Collection at the British Museum.

Knowledge & Science

We know for

certain that Alexander browsed one of the most famous private libraries of the

age: The library of the scientist Henry Cavendish. Cavendish’s private library

in Bedford Square, London, was open to scholars from about 1785 upon

application. This valuable library had around 9,000 titles in

12,000 volumes. The largest number of books was about natural philosophy –

including chemistry, mechanics, instruments and meteorology (about 2,000

titles). Another major category was mathematics, followed by astronomy. The

category of natural history covered mainly geology and mineralogy. Maps and

books about voyages were sorted in geography.

An application was only one of the conditions attached to accessing the library

of Henry Cavendish. The second condition was that a visitor was on no account

to presume so far as to speak to, or even greet, the owner should be happen to

meet him. Henry Cavendish was a very introvert person.

Meeting the Giants

Forster’s network in the scientific community was excellent and proved to be invaluable to Alexander. Forster was able to introduce his protégé to Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society. Banks showed Humboldt his huge herbarium, with specimens of the South Sea tropics. It was the beginning of a scientific friendship between Banks and Humboldt that lasted until Banks’s death. Alexander also met the landscape painters William Hodges and John Webber who both had accompanied Captain Cook on his expeditions. Forster also introduced him to Alexander Dalrymple, a geographer and hydrographer of the British Admiralty.

Scientific Sightseeing

A visit to Slough to see Mr. Herschel’s telescope would round of the scientific programme in London. On their journey, the men would also visit Soho / Birmingham, the caves at Castelton/Derbyshire, and Oxford.

The Call of Adventure

Despite the glamour of London and the excitement of networking and sightseeing, other things were on Alexander’s mind. One wall of his room in London was decorated with the print of a ship, depicting a vessel of the East-Indian Company sinking in a storm. Alexander later remembered that when looking at the picture with constant fascination, hot tears would ran down his cheeks. He wrote later in life that during the weeks in London, he had fancied to sign on as a sailor.

Alexander felt melancholy throughout the trip around England. The landscape of Derbyshire touched something inside him. In the caves of Castleton, surrounded by darkness, melancholy stroke again, leaving Forster to wonder why his young companion was so sad. It seems that Alexander began to understand during these weeks that a career as a civil servant would never do for him. Exploration, danger and adventure it had to be!

Aftermath

Georg Forster – one of the central figures of the Enlightenment in Germany – turned the impressions of the journey into a travel description titled “Views of the Lower Rhine, from Brabant, Flanders, Holland, England, and France in April, May and June 1790”. It was published from 1791–94. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe said about the book: “One wants, after one has finished reading, to start it over, and wishes to travel with such a good and knowledgeable observer.”

But Forster’s fame was declining. On the trip of 1790 via the Netherlands to England he had found the citizens’ freedoms well developed, and this shaped his ideals. The national uprisings in Flanders and Brabant and the revolution in France additionally sharpened his political opinions.

When the French took control of Mainz in 1792, Forster joined the movement “Friends of Freedom and Equality” and went on to play a leading role in the Mainz Republic. When Prussian and Austrian coalition forces regained control of the city, Forster was declared an outlaw. He died in revolutionary Paris of illness in early 1794.

His work became mostly forgotten, partly due to his involvement in the French revolution. In the period of rising nationalism after the Napoleonic era he was regarded in Germany as a “traitor to his country”. His work was rediscovered in the second half of the 20th century. The Alexander von Humboldt foundation named a scholarship program after him. He is now considered as one of the first and most outstanding German ethnologists.

Alexander von Humboldt didn’t become a civil servant, as his mother had wanted. He realised that such a steady career would never do for him. It was the free, flexible life as the one of Forster, with adventurous travels and experiences, that could fulfill him. After the death of his mother, Alexander awaited an opportunity to fulfill his long-cherished dreams of travel. He almost managed to go to Egypt with an expedition of Lord Bristol in 1798, but Lord Bristol was arrested as a British spy in Milan before the expedition could really begin. Finally, in 1799, Alexander was able to join a Spanish-American expedition. It would change his life. Alexander became a famous explorer and scientist. Though he and Forster never met again in person, the two men kept up a correspondence until Forster’s early death. Humboldt always gave Forster credit for being the formative influence in his life.

Related articles:

Sources

- Forster, Georg: Ansichten vom Niederrhein, von Brabant, Flandern, Holland, England und Frankreich im April, Mai und Juni 1790; 1791-1794. (https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb10105610_00005.html)

- Christa Jungnickel, Russell K. McCormmach: Cavendish; Amer. Philosophical Society, 1996

- Julius Löwenberg, Robert Avé-Lallemant, Alfred Dove: Life of Alexander Von Humboldt; hansebooks, 2019

- Erdmann, Dominik: Einführung. Zur Neu-Edition des Journals der England-Reise (1790); In: edition humboldt digital, hg. v. Ottmar Ette. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin. Version 4 vom 27.05.2019. https://edition-humboldt.de/v4/H0016430

- Dominik Erdmann und Christian Thomas (Hrdg) unter Mitarbeit von Florian Schnee: Alexander von Humboldts Englisches Reisejournal; in: edition humboldt digital, hg. v. Ottmar Ette. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin. Version 4 vom 27.05.2019. https://edition-humboldt.de/v4/H0017682/1r

- Anja Müller: Ein gemeinsames Band umschlingt die ganze organische Natur – Georg Forsters und Alexander von Humboldts Reisebeschreibungen im Vergleich; Fakultät I – Geisteswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie; Berlin 2011

- Jean Théodoridès: Humboldt and England; in: The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Jun., 1966), pp. 39-55 (18 pages)

- Martin Sauerwein, Katrin Sauerwein, Steffen Kölbel, Cathleen Buckow: Das Fragment des englischen Tagebuchs von Alexander von Humboldt; in: Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien, Bd. 9, Nr. 16 (2008)

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)