Transparencies – translucent hand-coloured prints or drawings – became common from around the 1770s. Their popularity peaked from the 1790ies until well into the early 19th century.

Transparencies were displayed at home or, in larger size, at nearly every kind of festivity from assemblies and dinners to astronomical lectures and theatres. You would find them at fairs, pleasure gardens and public celebrations.

How were transparencies made?

The simplest way was to add varnish from both sides to the highlights of an image you had painted on paper or a light textile, so that the material became translucent when held up against the light. There were also more elaborate methods based on painting with oil of turpentine. The best effects were achieved with emotive paintings that contrasted light and dark. Thus, Gothic and picturesque landscape scenes by moonlight were popular topics. Exhibited at night, they could shine with a number of candles or lamps behind them.

An accomplishment of ladies

Creating transparencies was considered a suitable art for ladies. Among the skills required for making them counted patience, preciseness and the delicate manipulation of the fabric or paper. What is more, the aesthetic qualities of transparencies – ‘radiant, ethereal, passive’ – accorded with the era’s image of an ideal woman.

A market for publishers and drawing-masters

The craze for making transparencies offered a market for drawing-masters, print sellers and publishers. As early as in 1784, Charles Taylor mentions transparencies in his drawing-manual for amateurs (The Artist’s Repository and Drawing Magazine, Exhibiting the Principles of the Polite Arts in their Various Branches). Soon, there were manuals on how to achieve the best effects in transparent painting, and DIY-instructions were published in women’s periodicals. Printmakers supplied ready-made materials and scenes. Drawing-masters taught transparent painting as part of their usual repertoire.

A transparency by JMW Turner

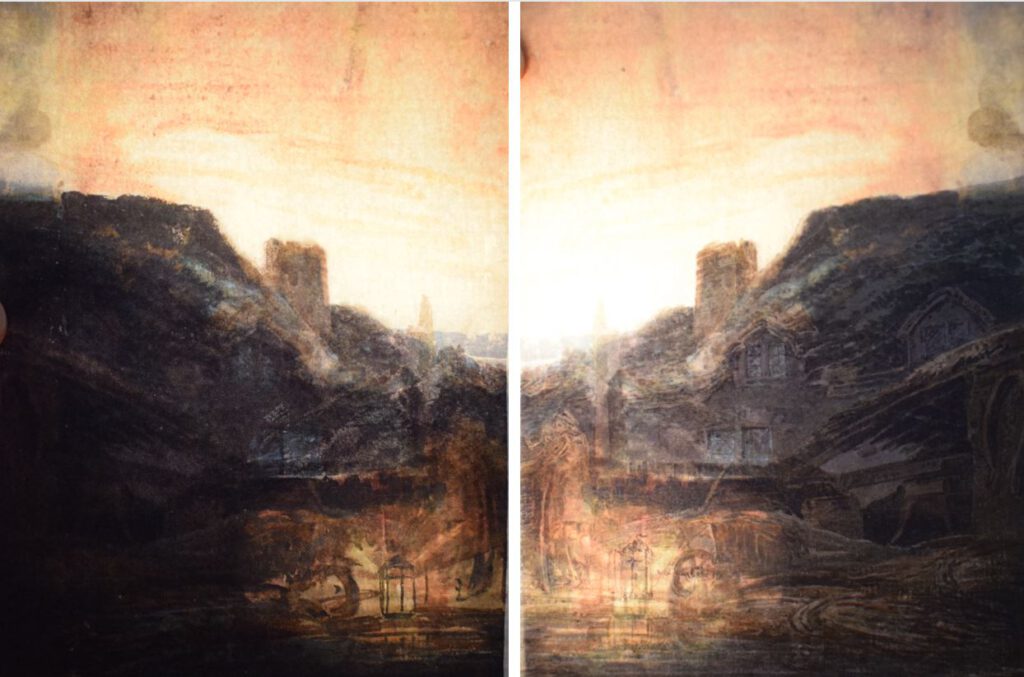

It is not surprising that the budding artist who became Britain’s most famous landscape painter also tried his hand in the art. Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was about 20 years old when he painted a sheet of paper on both sides with two different views with water colours (A Transparency: A Moss-Covered Cottage and Shed, with a Man Smoking and a Lantern, probably 1794-95).

He applied pigments in various concentrations. One side of the sheet bears intended washes to enhance the tonal contrasts on the recto. It is believed that JMW Turner didn’t adopt the usual practice of adding 1 -3 layers of varnish, but there are indications that he had oiled the paper lightly. Thus, when you placed a light source behind one side, the picture is supposed to change into an evening landscape by twilight.

Experiments with art: illuminating a transparency

I stumbled upon the transparency A Moss-Covered Cottage and Shed, with a Man Smoking and a Lantern at the exhibition “Tree Horizons” (28. October 2023 – 10. March 2024) at Lenbachhaus in Munich. Fascinated by it, I wondered how it would have looked when it was illuminated.

Of course, you can’t experiment with the original. As a simple workaround, I found a photo of both sides on the internet. I placed the printout on a tissue and applied a thin layer of oil on all light motives with a brush. Having removed the surplus oil with a tissue, I let the pictures dry over night. Then, I glued the sides together back on back. The two paintings match!

I found out that it takes a strong light source to illuminate my wannabe transparency properly. I am not sure such a light-source would have been around in the Regency period, even as the Argand oil lamp, which was patented in 1784, was several times more powerful than existing lamps (and helped to further the popularity of transparencies).

Nevertheless, I like the effect of the illumination: the evening sky glows over both sides, and the lanterns become a golden beacon. Is it possible that Turner’s original transparency would have looked like this?

Related articles

Sources

- “Transparency”, at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/x9730

- Andrew Wilton, ‘A Transparency: A Moss-Covered Cottage and Shed, with a Man Smoking and a Lantern 1794–5 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, April 2012, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/joseph-mallord-william-turner-a-transparency-a-moss-covered-cottage-and-shed-with-a-man-r1141110, accessed 19 November 2023.

- Exhibition „Three Horizons“, Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany

- John Plunkett, ‘Light Work: Feminine Leisure and the Making of Transparencies’, in Crafting the

- Woman Professional in the Long Nineteenth Century: Artistry and Industry in Britain, ed. by Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi and Patricia Zakreski (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 43-67

- Pei-Ching Sophia Huang, MA (University of York ): Women in their Worlds of Objects: Construction of Female Agency through Things in the Novels of Jane Austen and Elizabeth Gaskell being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD in the University of Hull, July 2015

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)