The 18th century sees an increase in scientific knowledge and practical research. Many findings have a direct impact on everyday life, craft and commerce. New technics allows, e.g., to create new colours. Find out here what Napoleon’s Campaign in Egypt, the Prussians and an apothecary have to do with the various blue pigments created in the long 18th century.

The 18th century sees an increase in scientific knowledge and practical research. Many findings have a direct impact on everyday life, craft and commerce. New technics allows, e.g., to create new colours. Find out here what Napoleon’s Campaign in Egypt, the Prussians and an apothecary have to do with the various blue pigments created in the long 18th century.

1706: When red turns to Prussian Blue

Johann Jacob Diesbach was a paint manufacturer in Berlin / Prussia. Legend has it that he discovered a new shade of blue by accident.

Diesbach had been in the process of making a red colour from crushed cochineal insects, iron sulphate and potash. When one batch of the product did not turn red, but from pale pink to purple and finally to a deep blue, he contacted the supplier of the potash, a certain Johann Konrad Dippel, theologian, physician and alchemist.

Together, they found out that the unexpected reaction had occurred because the potash sold by Dippel had been contaminated with bone oil. For some time, bone oil was deemed to be the alchemists’ dream of the ‘Elixir of Life’, but it mainly was a nitrogenous by-product of the destructive distillation of bones.

The new blue came in use quickly. From the beginning of the 18th century, Prussian blue was the predominant uniform coat colour worn by the infantry and artillery regiments of the Prussian Army.

The dark blue pigment Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue) was the first modern synthetic pigment, and the first stable and relatively lightfast blue pigment to be widely used. It replaced the expensive blue colour made from Lapis Lazuli.

1789: An Apothecary bags the sky

For many centuries, paint manufacturers had attempted to create sky blue colours. The results had been unsatisfactory as the pigments had a limited saturation and tended to discolour in reaction with other pigments.

In 1789, Swiss apothecary Albrecht Höpfner succeeded in inventing a blue pigment, opaque and bright due to its highly refractive particles, which did not react to light or chemicals. Höpfner called the new blue ‘coelinblau’ (cerulean, sky-blue).

To make the colour, he used English tin, aqua regia and erythrite. His first production line of coelinblau was limited and short-lived, as Höpfner went bankrupt. He kept experimenting privately, and created cerulean blue from cobalt stannate in 1805, profiting from the work of Louis Jacques Thénard (see below). However, the colour did not become widely available to artists until the 1860ies.

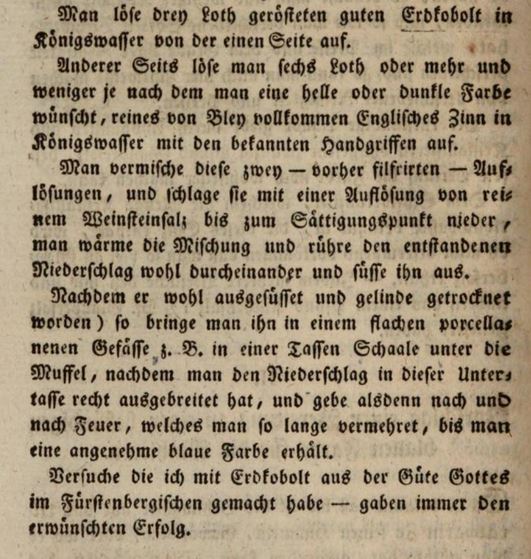

Being an apothecary, Höpfner strongly believed in professional ethics. He thus published his recipe for cerulean blue in a periodical he ran, so that everyone would be able to make the pigment.

Original recipe from 1789 for making cerulean blue :

Dissolve 3 lots (one lot is 1 1⁄32 of a pound) of roasted erythrite in aqua regia from one side. Dissolve 6 lots or more (depending how light or dark the colour should become) of pure English tin (lead-free) in aqua regia by the known method. Mix the two together – filter them before – and stir in a solution of pure potassium hydrogen tartrate, until saturated. Heat the mixture and recausticise it. When recausticised and dried, put it in a flat porcelain pot, such as a saucer, and place it under a muffle, after having spread the precipitate in the saucer. Add heat, and more heat, until a blue colour is achieved. Experiments conducted with erythrite from the mine „Guete Gottes“ in the area of Fuerstenberg always were successful.

(Albrecht Höpfner, 1789)

1798: Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign brings Egyptian Blue into fashion

Egyptian blue was rediscovered during Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign and become fashionable soon after. Scientists of the campaign had explored ancient sites and brought home artifacts, some of them glazed or painted with a light blue colour. The results of the scientific research were published in the book “Voyage dans la basse et la haute Egypte (Journey in Lower and Upper Egypt)”, written by Vivant Denon and published in 1802.

Ancient Egypt went on to inspiring everything from sofas with Sphinxes for legs or turban for lady’s evening fashion, to tea sets painted with the pyramids. The discoveries triggered numerous subsequent researches.

Additionally, in 1814, a group of scientists that included the British chemist Humphry Davy unearthed a pot of an unknown “pale blue colour” at Pompeii. Davy was particularly interested in the chemistry of ancient pigments, which he collected in both Pompeii and Herculaeum. He realised that he had rediscovered the material ‘of which the manufacture is said to have been anciently established at Alexandria’.

It was concluded that Egyptian blue was a synthetic pigment used in the early dynasties in Egypt until the end of the Roman period in Europe. It then became forgotten. Davy’s research was interrupted by Napoleon’s escape from Elba. Davy returned to London, as Europe prepared for war again.

Today we know that Egyptian blue can be synthesised by heating a raw material mixture consisting of quartz sand, limestone, copper ore and a flux (soda or plant ash) to about 950°C.

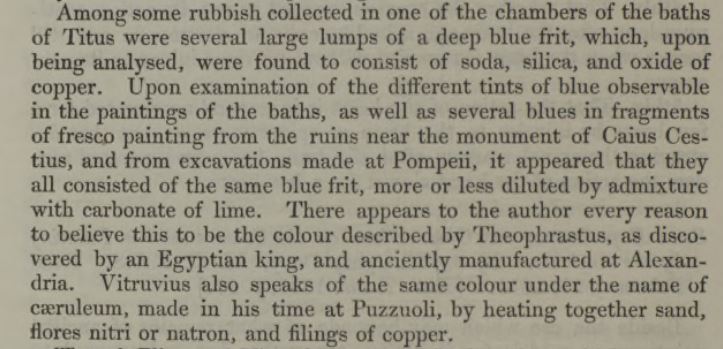

A discovery at Pompeii, reported by Humphry Davy:

Among some rubbish collected in one of the chambers of the baths of Titus were several large lumps of a deep blue frit, which, upon being analysed, were found to consist of soda, silica, and oxide of copper. Upon examination of the different tints of blue observable in the paintings of the baths, as well as several blues in fragments of fresco painting from the ruins near the monument of Caius Cestius, and from excavations made at Pompeii, it appeared that they all consisted of the same blue frit, more or less diluted by admixture with carbonate of lime. There appears to the author every reason to believe this to be the colour described by Theophrastus, as discovered by an Egyptian king, and anciently manufactured at Alexandria. Vitruvius also speaks of the same colour under the name of caeruleum, made in his time at Puzzuoli, by heating together sand, flores nitri or natron, and filings of copper.

(Humphry Davy, 1815)

1799: Cobalt Blue becomes the New Lapis Lazuli

The invention of Cobalt blue is credited to the French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard in 1799. The French Minister of the Interior had ordered Thénard to create an inexpensive blue – as beautiful as Lapis Lazuli – for the Sèvres Porcelain Manufacture, since the pigment had become scarce due to the war. Thénard was given 1,500 francs and went to work.

He soon came up with a pigment he made by sintering cobalt(II) oxide with aluminium(III) oxide at 1200°C. In 1804, after experimenting with various cobalt compounds, Thénard obtained a highly stable pigment with a deep and intense blue that could be made at lower cost. Commercial production began in France around 1807.

Cobalt blue quickly became the favourite blue of artists, including the English painter J.M.W. Turner. It is believed that the earliest recorded use of Cobalt blue in art is in the sky of J.M.W. Turner’s oil sketch of “Goring Mill and Church“. Another early adopter was Caspar David Friedrich who used Cobalt blue in the sky for his painting “Riesengebirgs Landscape with Rising Fog“. Turner continued to use Cobalt blue in many of his paintings, such as “Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus” and “Fighting Temeraire“.

Cobalt blue in ‘impure’ forms had already been used earlier, e.g., for Chinese porcelain. In the second half of the 18th century, artists and craftsmen had worked with other impure forms of cobalt blue. The first synthesis of a cobalt blue pigment (named ‘Leithners Blau’) is attributed to porcelain painter Josef Leithner, who used a cobalt aluminosulphate at a Vienna Porcelain Manufactory. However, his blue pigment was never industrially produced. In the 1770ies, a blue created from aluminium salts mixed with a cobalt solution was used at a Saxony Porcelain Factory. The process of creating the colour was considered a trade secret. In England, the first recorded use of cobalt blue as a colour name was in 1777.

Thénard discovered the pigment cobalt blue independently from its forerunners as a pure aluminium-based pigment. His Cobalt blue, established in the nineteenth century, was a greatly improved one.

Related articles:

Sources

- Coles, David: “Chromatopia. An illustrated history of colour”; Thames & Hudson, 2018

- www.winsornewton.com

- Cerulean Blue; in: http://www.theinfolist.com

- Albrecht Höpfner. “Einige kleine chemische Versuche vom Herausgeber”, Magazin für die Naturkunde Helvetiens, Band 4

- Pigments through the ages: http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/

- Dariz, Petra; Schmid, Thomas (2021): „Trace compounds in Early Medieval Egyptian blue carry information on provenance, manufacture, application, and ageing“, in Scientific Reports 11, 11296, doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90759-6, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-90759-6

- Davy, Humphry: “Some Experiments and Observations on the Colours used in Painting by the Ancients. Read February 23, 1815”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 105, p 97 (https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspl.1815.0008)

- Brack, Paul: “Egyptian blue: more than just a colour”, in: www.chemistryworld.com https://www.chemistryworld.com/features/egyptian-blue-more-than-just-a-colour/9001.article, 2015

- McCouat, Philip: “Egyptian blue: the colour of technology”, in www.artinsociety.com

http://www.artinsociety.com/egyptian-blue-the-colour-of-technology.html - Prussian blue: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussian_blue

- bleu de cobalt: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bleu_de_cobalt

- “Louis Jacques-Thenard” at https://www.wonders-of-the-world.net/Eiffel-Tower/Pantheon/Louis-Jacques-Thenard.php

- Barral, Miguel: “In Search of a Less Toxic Blue” at: https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/science/leading-figures/in-search-of-a-less-toxic-blue/

- Ashok Roy (2007) Artists’ Pigments, vol 4, ed Barbara H Berrie, Archetype. ISBN 978 1 904982 23 4; at https://eclecticlight.co/2018/02/07/pigment-cobalt-blue-the-19th-century-sky/

- Brown, Raymond Lamont: “Humphry Davy, life beyond the lamp”; Sutton Publishing Limited, 2004

- Kingston Lacy, Wimborne BH21 4EA / UK

- The National Gallery London, Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN, UK

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)