James Ogilvy, 7th Earl of Findlater, had two passions – one was for landscape architecture, the other was for men. Circumstances to enjoy these passions were far from ideal: practising same-sex love in Britain in the 18th century was considered a crime punishable by death. Thus, James decided to leave Britain for good in 1791. As a consequence, he had to give his estates in the care of a trusty, and with it all possibilities of putting his architectural talents into action – or so it seemed.

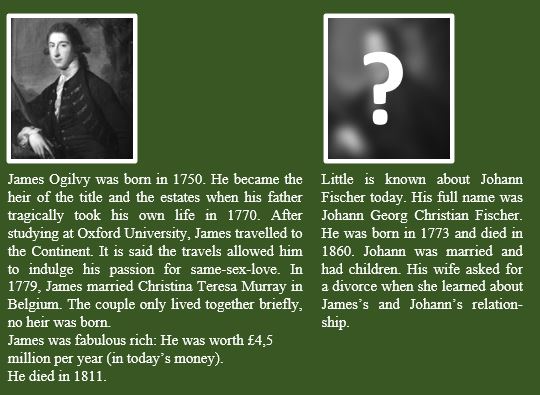

James spent the 1790s travelling on the Continent. His unsteady life took an unexpected turn when he met a certain Johann Fischer in the year 1800.

Johann Fischer was an architect by profession, and 27 years old when he met James in Berlin. The two men quickly became friends, and more than this: Johann was James’ private secretary, his constant travel companion, and his lover.

James and Johann: creators of paradises

Meeting Johann turned out to be a stroke of luck for James. Besides finding a partner for life, Johann was his chance to truly embrace his talent for landscape gardening and architecture.

Source: www.nationalgalleries.org

In the past, James had made some attempts to redesign the estates he had inherited in 1770. He was fabulously rich, and could afford commissioning even the leading architect Robert Adam to develop plans for a new house. Alas: these were plans only. James used to travel long and frequently to the Continent, which made architectural ambitions for the Scottish home difficult to carry out. Thus, he had to be content with minor projects such as Scottish architect James Playfair redesigning the kitchen gardens.

James also had begun to work on a book about architecture. For “Plans et dessins tirés de la belle architecture”, published in 1799 in Leipzig, he compiled the plates and contributed designs of his own work. However, with Johann by his side, carrying out most projects, he could reach far beyond publishing.

The first steps of the new architectural ‘career’ were made in Carlsbad/Bohemia, a famous spa town James used to visit for his health. As James was worth £4,5 million per year (in today’s money), he could and would easily spend some of his wealth on charity and new buildings for the town.

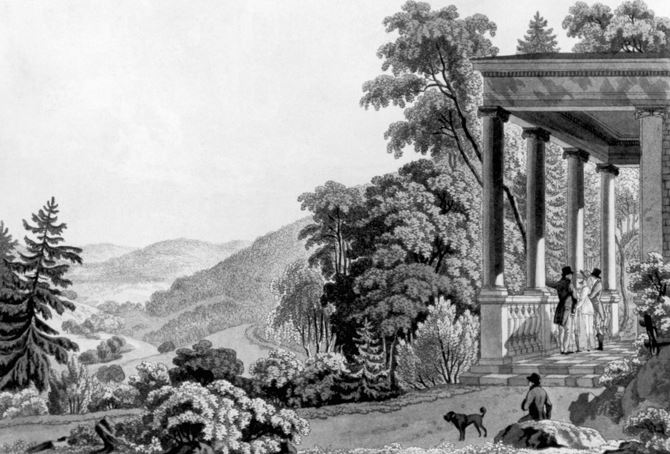

In 1801, James gave Carlsbad a neoclassical gazebo with Ionic columns. Findlater’s Temple looked over the idyllic scenery of Tepla valley. All in all, James would present Carlsbad with more than 20 buildings. It is thus no surprise that the city erected a monument in his honour.

The chance to do the first big project for the Saxonian aristocracy came in 1802: Countess Henriette von Schall-Riaucour needed assistance to turn her baroque garden at Gaussig House into an English landscape park. James and Johann took matters in hand and transformed the garden completely, keeping only a small canal and one pavilion. If you visit Gaussig House/Saxony today, you can still see the original design.

After this, James turned his interest to the beautifully located vineyards of the Dresden area. These had an excellent view on the river Elbe, with mountains in the distance. The vineyard-owners were not eager to sell. Besides, as a foreigner, James could not buy land. It was thus very handy that Johann could step in: He did the negotiations and it was him who bought the vineyards for James. He managed to get 5 of the 8 desired estates by 1805, spending 43,000 taler all in all (probably about £700,000 in today’s money). Johann also purchased Helfenberg Manor in the same area for James. The two men redesigned the house in the English style. To the park, they added a little lake, a small bridge and many valuable trees. At the top of the vineyard Bredemann James and Johann built a magnificent neoclassical palace with the help of famous master builder Johann August Giese. Giese had created the first garden in the English style in Saxony in 1788, and was commissioned by Counts and Princes. The house at Bredemann’s vineyard became known as Findlater’s Palais, and was considered ‘the most beautiful residence in Dresden’.

Why did James und Johann manage to live in a relatively open same-sex relationship?

James and Johann were living a love against all rules. How was this possible in an age that frowned upon same-sex love as a ‘crime against nature’?

First of all, we may not suppose James and Johann could show there love openly in society. However, on the Continent, romanticism had brought with it a new ideal of friendship. Homoerotic relations and sexual possibilities in all its forms could be comparatively easily integrated into this new ideal. Romantic circles were tolerant towards same-sex-love, and it was within these literary and scientific circles that James and Johann could build their life. Johann Wolfgang Goethe was among their good acquaintances around 1808, and so were many local noblemen and -women.

Secondly, in some countries of the Continent same-sex love was not prosecuted (as it was in Britain). This doesn’t mean that these countries were a safe haven where homosexuals could display they affection openly. But it did mean that the risks were considerably lower.

In France, a criminal code had been introduced in 1791 that redefined the meaning of a “true crime”. This meant that private acts by private individuals were not considered as a matter for state intervention. As a consequence, former crimes such as blasphemy, witchcraft, and also ‘sodomy’ were decriminalised. The law became part of the Code civil which was introduced in France under Napoleon. Having this said, we must keep in mind that Napoleon’s government never showed itself particularly tolerant of homosexual activities. The law no longer penalised “crimes against nature”, but repressive actions were taken against an open display of same-sex-love. Yet, whatever happened behind closed doors was of no concern.

In the Holy Roman Empire, to which most nations of the German states belonged, homosexuality was punishable by death until 1806. However, Frederick the Great had suspended the use of the death penalty for sodomy in 1746 in Prussia, and in 1794 the death penalty for homosexual acts was abolished. The influence of the Napoleon’s Code civil sparked further decriminalisation in most German states.

These circumstances allowed James and Johann to share 11 years with each other. When James died in 1811, he bequeathed his property in Saxonia to Johann, who continued to live at Helfenberg Manor until his own death in 1860. James and Johann have found their final resting place in the same grave in Loschwitz/Saxony.

Related articles

Sources

- Kate Aaron: Homosexuality and the Napoleonic Code; Sep 10, 2015: https://medium.com/gay-old-times/homosexuality-and-the-napoleonic-code-2a0a1e31d817

- Eva Fischer: Vom Bergpalais Findlater zum Schloss Albrechtsberg und dem Pionierpalast „Walter Ulbricht“, Cossebauder Infoblatt, vol. 12/2019

- Larry Houston: Homosexuality in Great Britain Section Two: Legislation, 21 March 2017 at: http://www.banap.net/spip.php?article156

- W, Nedobity: Lord Findlater and his impact on continental landscaping; in: European Journal, year 10, no 1, June 2009

- Michael David Sibalis: The Regulation of Male Homosexuality in Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, 1789–1815; in: Jeffrey Merrick and Bryant T. Ragan: Homosexuality in Modern France, Oxford University Press, 1996

- David Tacium: ‘Warm Brothers’ in 18th-century Berlin; in The Gay &Lesbian Review, July-August 2019: https://glreview.org/article/warm-brothers-in-18th-century-berlin/

- Rembrand Ulrich: Die Eigentümer der Weinberge an den Dresdner Elbhängen; at: http://www.weinberglingnerschloss.de/historie/1032-die-eigentuemer-der-weinberge-an-den-dresdner-elbhaengen

- wikipedia.com

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)