May I have the pleasure of this Waltz? It is the most controversial dance of the Regency Period. That the Waltz was considered scandalous certainly isn’t new to you. But there were more reasons than too much intimacy between the dance partners that made people turn up their noses at the Waltz. Among the despisers was e.g. Lord Byron who can hardly be counted among the moralisers of the age. So what was wrong with the Waltz? Continue reading

May I have the pleasure of this Waltz? It is the most controversial dance of the Regency Period. That the Waltz was considered scandalous certainly isn’t new to you. But there were more reasons than too much intimacy between the dance partners that made people turn up their noses at the Waltz. Among the despisers was e.g. Lord Byron who can hardly be counted among the moralisers of the age. So what was wrong with the Waltz? Continue reading

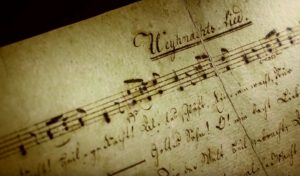

When the church organ broke down on Christmas Eve in 1818

It’s Christmas Eve, about 200 years ago. The church organ has broken down in a small town in Austria. The aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars still haunts the people. In this night, a very special song is born. Nobody knows yet that it is to become one of the most popular carols in the world. Continue reading

It’s Christmas Eve, about 200 years ago. The church organ has broken down in a small town in Austria. The aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars still haunts the people. In this night, a very special song is born. Nobody knows yet that it is to become one of the most popular carols in the world. Continue reading

You are not really dressed until you are wearing a hat

Dear time travelling gentleman on the way to the 18th century, please make sure to take with you one thing: a hat!

In the 18th century, a hat is not only useful in bad weather, and it is more than a fashion accessory. A hat indicates your role in society. Without a hat you are a nobody.

Follow me to a brief introduction to the history of 18th century hats. We make sure you pick the correct one for each period, and we also find out about hat etiquette.

Ladies’ Hats made from Horsehair

During the Regency period, horses seemed to be everywhere: They were indispensable partners for work, transportation, warfare, sport – and even for lifestyle and fashion. Horsehair from manes and tails was used for brushes, wigs and string instruments, and it was proceeded into haircloth. Haircloth was a great fabric for upholstery or for stiffening crinolines and the front panels of a suit. All these usages relied on the robustness of the material. But did you know that delicate ladies’ hats were made of horsehair, too?

Continue readingSign your name across my card

How to use a dance card in the Romantic Age

For a young lady few things would be more satisfying than being a sought-after dancing partner at a glamourous ball. But if she was in constant demand, how would she keep track of the partners engaging her for the waltz or the cotillion later in the evening? And how would a gentleman secure a dance with her?

Keeping track of the gentlemen who had promised a dance in the course of the evening was done – on the Continent – with the assistance of a so called ‘carnet de bal‘ (a dance card). A gentleman would ask a lady to write down his name on the card a for a specific dance. These small and often precious carnets de bal were very popular in France and Austria throughout the 18th century.

In Britain, the dance card became fashionable at around the turn of the 18th century. The carnet de bal initially was often less elaborate than the Continental model.

Go Greek: the hairnet as a fashionable head-dress of Empire Style Fashion

Hairnets were popular for hairdressing in various historical periods. Today, we most often associate them with the ornate hairstyles of the Tudor period. Did you know that the hairnet became fashionable for a couple of years during the Regency period?

Continue readingEleonore Wickham: The Master Spy’s Wife

On 25th September 1799, shortly before 5 o’clock in the morning, the Wickhams woke up by the sound of guns. Were the French marching against Zurich again? William Wickham (1761 – 1840), England’s leading spy on the Continent, placed his wife Eleonore (1763-1836) under the care of his private secretary, the Count of St. George. He himself rode out reconnoitring the situation. Continue reading

On 25th September 1799, shortly before 5 o’clock in the morning, the Wickhams woke up by the sound of guns. Were the French marching against Zurich again? William Wickham (1761 – 1840), England’s leading spy on the Continent, placed his wife Eleonore (1763-1836) under the care of his private secretary, the Count of St. George. He himself rode out reconnoitring the situation. Continue reading

How to counterfeit tea: a guide for ruthless dealers in the 18th century

Let’s imagine you are a dealer of tea in London during the 18th century. Over the past decades, tea, once the luxury product for the super-rich, has reached the middle and lower classes. It is highly popular. This means a large target group for your product, but also a higher demand that must be met in times of war, trade embargos and economic depression. Tea leaves are expensive and there are heavy duties on it payable to government.

In short: Times are rough, life is hard – it thus seems rather pardonable to find ways to enrich yourself by certain methods one might call imitating tea (‘counterfeit’ is such a harsh word). Nobody will ever find out, and of course, you don’t mean to harm anyone. Plus, you are doing a favour to the lower classes that would not be able to enjoy a nice cup of tea at all if they had to pay the prices for genuine tea. Right?

Now, let’s see how tea was be imitated in the 18th century …

Amazing dessert of 1801: Tempt the palate with luxurious ‘Devilled Almonds’

Imagine you are a talented cook in London in the year 1801. You have just hired the rooms for your own tavern, and you are eager to make it a hit with well-off customers. Fortune is on your side: You can get a copy of the first cooking book published by John Mollard, the famous chef of prestigious 18th-century London restaurants catering to high-quality customers. It covers all his great recipes. With the help of this book, you compile your menu easily. Finally, all you need is a brilliant idea for the dessert. Cake, sweetmeats … or something really special? Your eyes alight at “Devilled Almonds”: Great name, and almonds are quality food. Read here how to prepare the dish in 1801, and what to consider when buying the ingredients.

Continue readingSteam, steel and beets: How 5 innovations made the cake cakier

Imagine you are a chef in a genteel household around 1815. Your master and mistress enjoy eating cake, and they also like to boast of the quality of ‘their kitchen’ to the guest of their dinners and assemblies. So, they constantly urge you to stay abreast of the latest trends in baking. Cakes at Royal Parties, they hear, are of a fluffy texture and delicious sweetness.

They give you free rein to achieve similar results, whatever the cost and changes to the kitchen may be. Check out five innovations that help you to succeed in this task. But be aware: baking powder is not yet available!