Before reading this post, please note that The Writer’s Travel Guide does not recommend travelling to Japan in the long 18th century. In all likelihood, you will not be allowed to enter the country. If you try anyway, you are committing a capital offence.

Before reading this post, please note that The Writer’s Travel Guide does not recommend travelling to Japan in the long 18th century. In all likelihood, you will not be allowed to enter the country. If you try anyway, you are committing a capital offence.

Having read this, you are still determined to give it a try? – excellent! You are of one mind with three British captains who each had an individual adventure with an island kingdom barring itself from foreign influences. And you might also find out that not all encounters have to be riddled with conflicts.

The briefest introduction to Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu

18th century knowledge about Japan

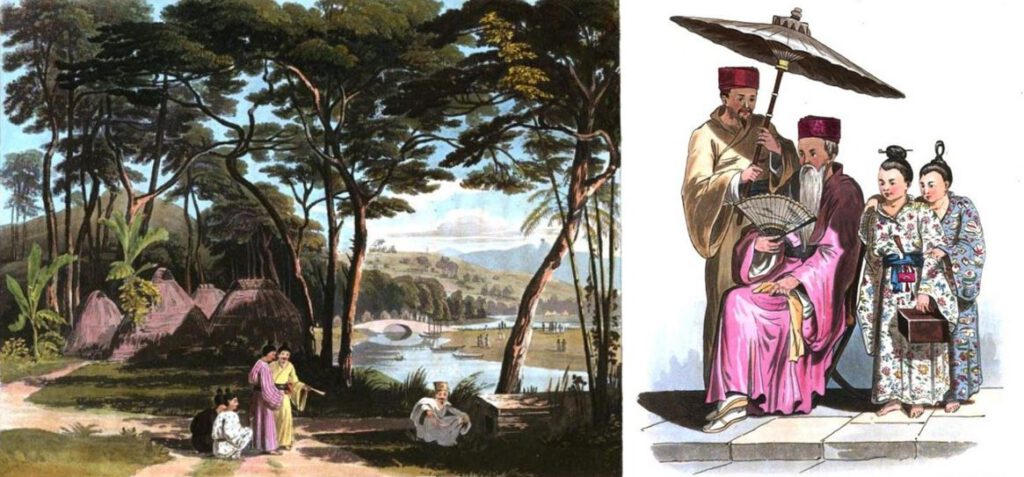

Let’s phrase it like this: For most part of the 18th century, the British knew as much about Japan as a person today would if he /she had only ever watched the movie “Shogun” with Richard Chamberlain. The problem was that this knowledge was a bit outdated even in the 18th century. It was largely based on the experience of William Adams, who had lived in Japan from 1600 to 1620, and had exchanged letters with the East India Company in London.

From 1724, you could boost your knowledge by reading the “History of Japan” by Engelbert Kaempfer, who had stayed in Japan from 1690 – 1692. In 1795, a knowledge update was available in the form of “Travels in Europe, Africa, and Asia, made between the years 1770 and 1779”, by Carl Peter Thunberg, a Swedish naturalist who had stayed in Japan from 1775 – 1776.

Japan’s international relations in the long 18th century

Basically, relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited. Common Japanese people were kept from leaving the country by pain of death. Nearly all foreign nations were barred from entering Japan. This excluded China, Korea and The Netherlands, which were allowed to trade from specially designated ports or places. The Kingdom of Ryukyu was incorporated into the Shogunal system and became a vassal state to Japan in 1609. It retained de jure independence, with King Shō Kō as ruler (1804 – 1828). Strict limitations for entering the islands were in effect, too.

Though relations and trade were restricted to certain nations and ports, Japan was not totally closed. The shogunate (i.e., the feudal military government) engaged in discussions with Dutch and Korean representatives to ensure that trade kept going well. Western scientific, technical and medical innovations flowed into Japan through the Dutch. The first Japanese-English dictionary was created in 1812 for governmental use.

The world outside knocks at Japan’s doors

Keeping up strict regulations was not always easy. From 1797 to 1809, several American ships managed to trade in Nagasaki under the Dutch flag. This had been initiated by the Dutch, as, due to their conflict against Britain during the Napoleonic Wars, the Dutch were not able to send their own ships.

In 1814, ships sent by Sir Stamford Raffles from Java tried to open up the country for trade with Britain. Besides, from around 1800 to 1820 every now and then foreign war ships, trade ships or whalers turned up at the Japanese coast, asking for provision or trade relations.

Japan reacted either with sending provisions to the ship, sending the ship away, taking prisoners – it was rather unpredictable. The isolationist foreign policy ended in 1854.

Your encounter with Japan in the 18th century

Understanding that your travel destination remains somewhat elusive, you nevertheless bravely step into the shoes of adventurous British captains. Let’s find out who of the three men is closest to your character – and which adventure thus would have been yours – by answering the following three questions. Count your points to get a proper result, and then read on to learn more about the challenges the real historical captains had to face.

Question 1:

Your ship is approaching a Japanese harbour. What do you do?

A) I sail into the harbour under a false flag to appear as the friendly Dutch nation that is allowed to trade in certain areas. I demand provisions.

B) I make a formal request to enter the harbour, and also ask to be allowed to return with a cargo, for the purpose of trading.

C) I explain that one of my ships had sprung a leak in last night’s violent weather. Therefore, I am obliged to repair the damages and thus need a safe harbour. I also need provisions and will be happy to pay for it.

Question 2:

What do you do during your time in Japan/in the Kingdom of Ryukyu?

A) After a cautious introduction, some officers and I are invited ashore. Later, we meet the Prince and are royally entertained.

B) I wait on my ship in Uraga bay for an official reply and get in contact with the clever official translator who is interested in all kinds of science. We have very interesting discussions on board of my ship.

C) While the Japanese officials sort out my crew’s identities, I take hostages and threaten to kill them if my demand for provision is not met. I fire cannons and muskets to press my demand.

Question 3: What is the result of your actions?

A) I am presented with a letter by the King of the island, to be delivered to my Sovereign. When we depart, hands are shaken in farewell, and some tears shed. One of my men writes a long poem on leaving our hospitable friends, others compile a dictionary of the local language.

B) The governor collects troops to attack my ship. Their plan is to burn it by means of 50 small boats filled with combustibles. My ship escapes narrowly as, having been provided with supplies, I release the prisoners and leave the harbour faster than the Japanese plans can be put into action.

C) I am treated with the greatest kindness and good will. Provisions and anything I might be in need of are offered to me. However, I am given to understand that only two nations, the Dutch and the Chinese, are permitted to trade with Japan, and only at Nagasaki. Thousands of people watch me leave, some make sketches of my ship, and many follow my ship for several miles at sea.

Count your points

Q 1: A) 5 Military daring points B) 3 Trade skill points C) 2 Friendship points

Q 2: A) 5 Friendship points, B) 5 Trade skill points C) 3 Military daring points

Q 3: A) 3 Friendship point, B) 2 Military daring points, C) 2 Trade skill points

Here is your result

You have the highest score in Military daring points

You are Captain Fleetwood Pellew of HMS Phaeton, who provoked the so called “Phaeton Incident” in Nagasaki in 1808. Continue here: Captain Fleetwood Pellew

You have the highest score in Trade skill points

You are Captain Peter Gordon of the brig “Brothers”, an adventurous tradesman and freelance vaccination influencer, trying to trade with Japan in 1818. Continue here: Captain Peter Gordon

You have the highest score in Friendship points

You are Captain Murray Maxwell of HMS Alceste, expedition commander of the diplomatic mission of Lord Amherst in 1816. Continue here: Captain Murray Maxwell

Captain Fleetwood Pellew

Background information

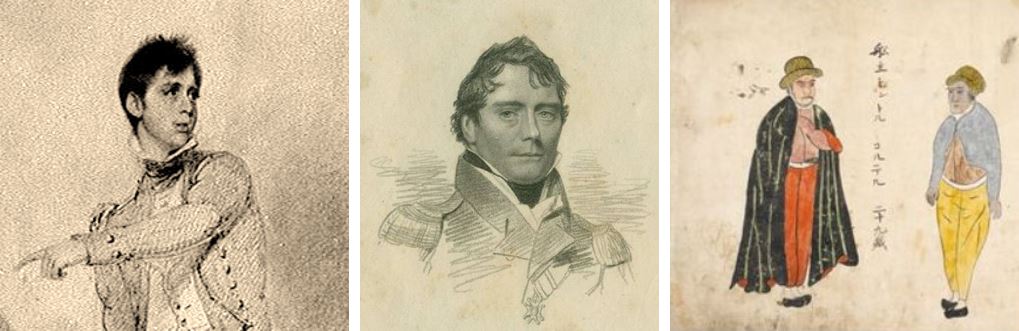

Fleetwood Pellew (1789–1861) was the second son of Admiral Edward Pellew (the one you know from the “Hornblower” series). He had a reputation for daring, but also for harshness. He was at sea from the age of 10, and became the captain of the HMS Phaeton in 1808.

Adventure in Japan

Fleetwood’s task was to hunt down Dutch ships. In doing so, he came near the Japanese coast, and tried to ambush some Dutch ships upon entering their safe haven, Deshima / Nagasaki. Fleetwood sailed into the harbour under the Dutch flag to appear as a friendly nation. The unsuspecting Japanese sent a boat to welcome the HMS Phaeton. They soon learned that they were tricked. While the Japanese officials sorted out the crew’s identities and intentions and what to do with them, Fleetwood had a boat with 15 sailors lowered to the sea. These sailors proceeded to seize the Dutchmen who accompanied and assisted the Japanese inspectors, and led them back to the HMS Phaeton at gunpoint. Fleetwood demand water and provisions, threatening to kill the persons he had abducted, and to burn the Japanese and Chinese ships in the harbour if his demands were not met. He also fired cannons and muskets to press his demands.

Panic broke out in Nagasaki. The officials consulted what to do. In the end, their plan was to collect troops to attack the foreign ship and to burn it by means of 50 small boats filled with straw and other combustibles. The HMS Phaeton escaped narrowly as, having been provided with supplies, Fleetwood released the prisoners and left the harbour faster than the Japanese plans could be put into action.

Effects of the adventure

On the Japanese side, the incident was a shell shock: The two heads of the port’s fortification were ordered to commit suicide, while the intelligence officer was stripped of his post. All residents of the area were subjected to a variety of punishment measures, such as closing their shops, and for a time they were forbidden to leave the domain and to travel. The system of warning of harbour intrusion was improved, as were the weapons and fortifications of the port. British subjects were from now on top of the list of personae non grata. The government promulgated a law prohibiting foreigners coming ashore, on pain of death.

Read about: Captain Murray Maxwell

Read about: Captain Peter Gordon

Captain Peter Gordon

Background information

Little is known of the personal background of the adventurous Scottish Captain Peter Gordon (fl. 1809 -1841). It is most likely that his father went to the sea as well. Peter became a sailor, and being second mate in the barque Joseph in 1809, was taken prisoner by the French on a voyage from Oporto to England. He escaped in 1810 and went to sea again. He began to trade from Calcutta, and travelled in South East Asia, India, Siberia and the Persian Gulf. He was described as a lively character, and as “inclined to be critical of the system” (other said he was a militant reformer).

Adventure in Japan

In July 1818, Peter entered the Uraga bay in front of the Japanese capital Edo in his brig “Brothers”, with 6 men on board and goods from the British market. His plan was to start trading, and to go ashore to see the shogun’s palace. He also hoped to be allowed to stay in Japan long enough to learn the language. To enter the harbour, he joined the “Brothers” with some junks that were returning home, and thus managed to remain undetected as a foreign vessel until the sun set. At night, the ship drifted near a rock and had to anchor. In the morning, officials had spotted the foreign ship and rowed out to inspect it.

Peter made a formal request to enter the harbour, and also asked to be allowed to return with a cargo, for the purpose of trading. While waiting for the official reply, he was visited by inspectors asking many questions. They were interested in scientific instruments, and so Peter showed them the ones he had on board. The Japanese knew the instruments’ names and uses well; and they observed that instruments were made much better in London than elsewhere. References were made to politics, such as to the return of Napoleon, and to the battle of Waterloo. “Our visitors were much interested in the account of that engagement, and an enumeration of the different states who were there combined against France”, Peter noted.

On the fourth day of his stay in the bay, Peter received a visit from two interpreters. Each of them could speak a little English, and they were able to understand English books by the aid of a Dutch and English dictionary. Nevertheless, all communication was in Dutch.

Influencing scientific progress

Science was a topic of interest. Peter had with him samples of a vaccine against the small pox (vaccinations against small pox had become widespread in South East Asia due to an initiative of Sir Stamford Raffles from Java). Peter offered the interpreters to make the method of vaccination a gift to them. With a heavy heart they had to decline, as receiving gifts was strictly forbidden However, it was the turning point that later let one of the interpreters, 31-year-old Baba Sajuro, to translate a Russian book on small pox vaccination and thus take a first step towards smallpox vaccination in Japan. The concept of immunization was started in Japan in 1849.

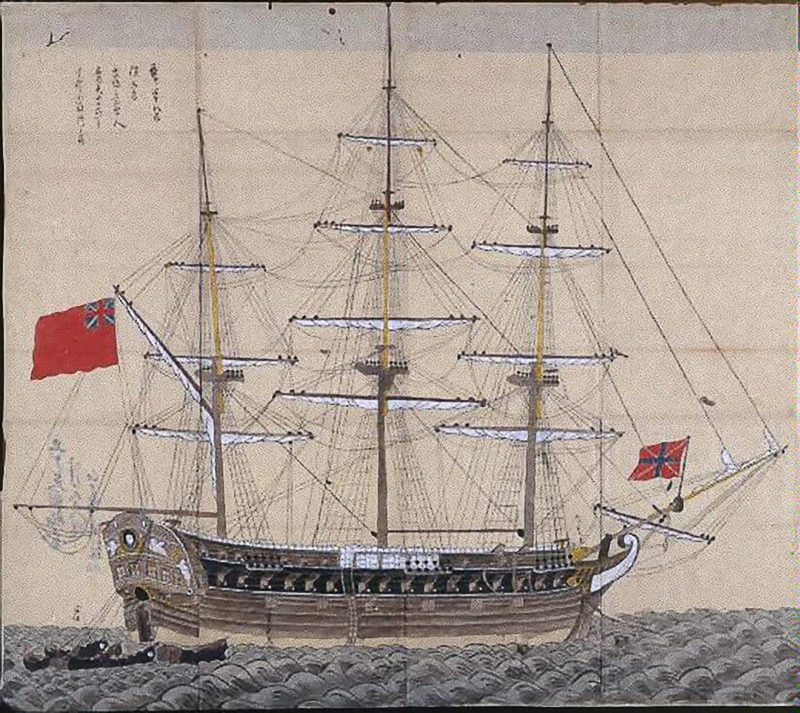

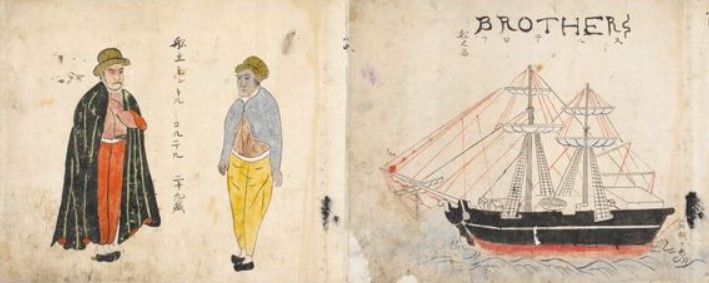

While staying in the bay of Uraga, Peter was treated with the greatest kindness and good will. Provisions and anything he might be in need of were offered to him. However, he was given to understand that only two nations, the Dutch and the Chinese, are permitted to trade with Japan, and only at Nagasaki. Thousands of people watch him leave, some made sketches of his ship. Once at sea, many Japanese boats followed the Brothers.

Peter observed: “In the course of that and the following day, there were not less than two thousand persons on board, all of whom were eager to barter for trifles. I had the pleasure of obtaining, amongst other things, some little books and other specimens of the language; and distributed two copies of the Chinese New Testament, together with some Chinese tracts. If inclined to set any value on ideas which can be formed concerning the hearts of men, especially of men accustomed to disguise their feelings as we are informed the Japanese are, I would definitively say that our dismissal was regretted by all.”

Read about Captain Murray Maxwell

Read about Captain Fleetwood Pellew

Captain Murray Maxwell

Background information

Captain Murray Maxwell (1775-1831) was born into a seafaring family. He entered the navy at the age of 15, and he became a captain in 1803. He was noted for the “dashing nature of his services” in the Mediterranean with his ship HMS Alceste. At the desire of Lord Amherst, who was to go as ambassador to China in 1816, Murray took part of the mission as expedition commander. Having set down Lord Amherst in China, Murray and the HMS Alceste and Captain Basil Hall from the HMS Lyra continued to explore the region.

Adventure in the Kingdom of Ryukyu

After stormy weather, the ships anchored in a bay of the Ryukyu Islands, near Naha. To the officials that arrived, Murray explained that one of his ships had sprung a leak in violent weather, and that he was obliged to repair the damages and thus needed a safe harbour. He also needed provisions and would be happy to pay for it.

At first, Murray and his crew were prevented from going ashore, as it generally was forbidden to foreigners to do so. They were treated very kindly and were provided well with all kind of supplies (and they never had to pay for it). After becoming more acquainted with the islanders, the British were allowed to enter the country and to stay in a specially designated area. The locals also took care of the sick of the ship. When Murray broke his finger from a riding accident, he was expertly treated by the local physician.

Captain Maxwell’s gentleness and forbearance, and his uniform attention to the wishes of the natives, and the great personal kindness which he had shewn to so many of them, had very early won their confidence and esteem.

(Captain Basil Hall)

The crew spent several months with the islanders, learning about their language, customs and traditions. “A mutual friendship began to exist between us; confidence took place of timidy”, noted Captain Hall.

That proud and haughty feeling of national superiority, so strongly existing among the common class of British seamen, which induces them to hold all foreigners cheap, and to treat them with contempt, (…), was, at this island, completely subdued and tamed by the gentle manners and kind behaviour of the most pacific people upon earth. Although completely intermixed, and often working together, both on shore and on board, not a single quarrel or complaint took place on either side during the whole of our stay; on the contrary, each succeeding day added to friendship and cordiality.

(John McLeod of HMS Alceste)

Meeting the Prince and celebrating a King

Finally, the captains and some officers were invited to meet the Prince and were royally entertained. The islanders joined them in celebrating the anniversary of the coronation of George III., providing many coloured paper lanterns to illuminate the ships at night, in honour of the British King. Murray was presented with a letter by the King Shō Kō, to be delivered to George III. It stated the happiness the king felt in having had the opportunity of affording an asylum to the ships, and expressing a hope that the attentions he had been able to show the British during their stay might prove satisfactory to the British King.

Parting as friends

On the day of departure, the islanders arrayed themselves in their best apparel, and prayed at the temple to restore their friends in safety to their home country. Presents were exchanged, hands were shaken in farewell, some tears shed. One of Murray’s men wrote a long poem on leaving their hospitable friends, others compiled a dictionary of the local language.

Read the original reports of the travel here:

John McLeod: Voyage of His Majesty’s ship Alceste, along the coast of Corea, 1818

Read about Captain Peter Gordon

Read about Captain Fleetwood Pellew

A few words to end this post

I hope you enjoyed your travel to Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu in the 18th century. We found out that you actually may be lucky and be able to enter the Kingdom of Ryukyu – despite all restrictions. It is otherwise with Japan. We also found out that the behaviour of the travellers is crucial to the success of the voyage.

If the adventures of the British captains can teach us anything, it may be that mutual understanding can overcome conflicts. It cannot overcome existing politics – at least not quickly. But it is the first step towards it.

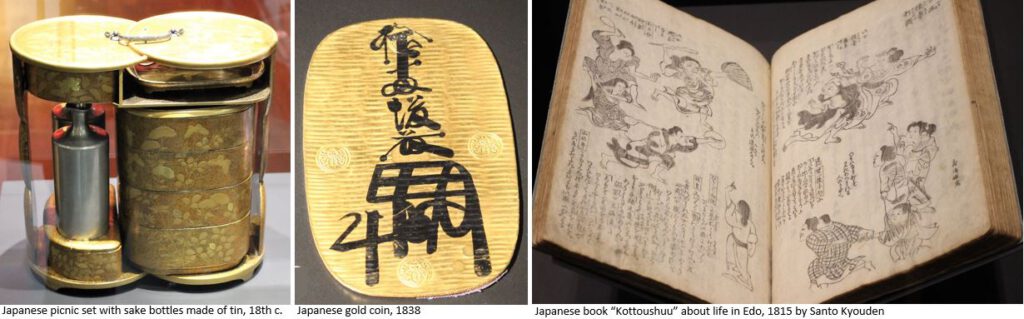

Enjoy here a selection of photos showing objects of 18th-century and early 19th-century Japan:

Related articles

Sources

Nyri A. Bakkalian, Ph.D. : (Friday Night History) The Phaeton Incident; at Riverside Wings A Historian Fashionista’s Roadtrips, Research, and Kickass Style, February 2021 at: https://riverside-wings.com/2021/02/26/389/

Louise Cowan: Travel Thursday – The Voyages of the Alceste; University of Reading, 11 February, 2016 at https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/2016/02/travel-thursday-the-voyages-of-the-alceste/

Harry Emerson Wildes: Aliens in the East: A New History of Japan’s Foreign Intercourse; Philadelphia, 1937

Eckhardt Fuchs, Tokushi Kasahara, Sven Saaler (editors): A New Modern History of East Asia; V&R unipress GmbH, 2017

Christopher Goto-Jones: Modern Japan: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions Book 202) (English Edition) OUP Oxford; 2009

Basil Hall: Account of a Voyage of Discovery to the West Coast of Corea and the Great Loo-choo Island; with an Appendix Containing Charts, and Various Hydrographical and Scientific Notices. By Captain Basil Hall, Royal Navy, F.R.S. Lond. & Edin. Member of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta, of the Literary Society of Bombay, and of the Society of Arts and Sciences of Batavia. And a Vocabulary of the Loo-Choo Language, by H. J. Clifford, Esq., Lieutenant, Royal Navy, London, 1818

John Knox Laughton: Maxwell, Murray ; in: Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900; 1894.

Elizabeth Mary Hill: (Gorski Vijenac): A Garland of Essays Offered to Professor Elizabeth Mary Hill, volume 2, Modern Humanities Research Association. Publications of the Mhra, 1970

Ann Jannetta : The Vaccinators: Smallpox, Medical Knowledge, and the ‘Opening’ of Japan; Stanford University Press, 2007

John McLeod: Voyage of His Majesty’s ship Alceste, along the coast of Corea, 1818

Robert Montgomery Martin: China; Political, Commercial and Social: In an Official Report to Her Majesty’s Government, 1847

Thomas O’Flynn: The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qājār Persia, c.1760–c.1870, Brill, 2017

Carl Peter Thunberg: Travels in Europe, Africa, and Asia, made between the years 1770 and 1779, volume 3, 1795

The Chinese Repository: Intercourse with Japan: notices of visits to that country by the Brothers, captain Peter Gordon; the Eclipse; and the Cyprus; The Chinese Repository, volume 7, 1839

Hamish Todd: “Japan400 – Hirado and the British in Japan”, Asian and African studies blog, 2013, at: https://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/asian-and-african/2013/08/japan400-hirado-and-the-british-in-japan.html

Noell Wilson: “Tokugawa Defense Redux: Organizational Failure in the “Phaeton” Incident of 1808”, The Journal of Japanese Studies; Vol 36, No.1, Winter 2010, pp. 1-32 (32 pages), published by: The Society for Japanese Studies (https://www.jstor.org/stable/20752489)

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)