The purple-blue blossoms of the wisteria delight the eye, and their sweet fragrance enchants the soul. Today, this beautiful plant adorns gardens, cottages and manor houses across Britain. The popular Regency-era series Bridgerton shows Bridgerton House with wisteria in full bloom climbing up the facade. But is this historically accurate? Did wisterias bloom in gardens during the Regency period? And would Jane Austen have enjoyed the blossoms, too? Let’s find out.

Good news: 18th century Britain knew a plant we now recognise as wisteria. However, it was not yet known by that name. The vine with its twining stem and blue, drooping racemes had been collected by British botanists in North America as early as the 1720s and brought to Britain as seed. Here is the story of its discovery, cultivation, and naming:

The Great Catesby

Mark Catesby (1683–1749) had a passion for natural history and adventure. The son of a local politician and gentleman farmer, he travelled to Virginia in 1712, visited the West Indies in 1714, and returned home in 1719, bringing with him many seeds and botanical specimens. Sharing these with botanists soon earned him recognition among gardeners and natural philosophers. In 1722, members of the Royal Society commissioned him to undertake a plant-collecting expedition to Carolina.

Catesby set sail for America in May 1722. Based in Charleston, South Carolina, he travelled throughout the colony for four years, collecting plants and animals. Among the seeds he sent back were those of what would later be known as Wisteria frutescens—although it was not yet called by this name. It became known as the ‘Carolina Kidney Bean’. These were the first seeds of their kind to arrive in Britain in 1724. They proved to be fruitful.

The first people in Britain to successfully grow Wisteria frutescens from Catesby’s seed were:

- Peter Collinson (1693–1768), a haberdasher and keen horticulturist, who grew the ‘Carolina Kidney Bean’ in his garden in Peckham.

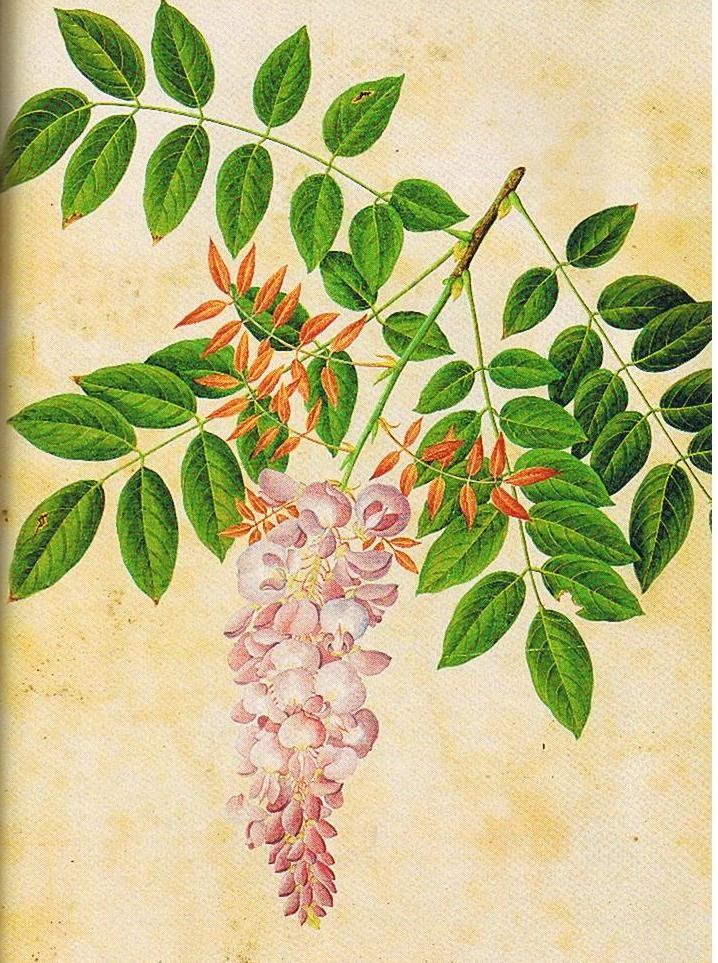

- Robert Furber (1674–1756), a nurseryman, was the first to raise flowering plants. He commissioned the artist Pieter Casteels to paint the plant in 1727.

- Philip Miller (1691–1771), a nurseryman, cultivated the species in the Chelsea Physic Garden. In the Catalogus Plantarum, which he edited in 1730, he referred to the plant as Phaseoloides frutescens Caroliniana. An unfinished watercolour from 1738 by the artist Georg Ehret depicts Wisteria frutescens under this name.

The plant became popular among botanists, who managed to cultivate it successfully in Britain’s climate:

- The Botanic Garden in Edinburgh proudly listed a Glycine frutescens—as the plant was then called—in its Catalogue of Trees and Shrubs in 1775.

- By 1789, William Aiton had cultivated a Glycine frutescens at the Royal Garden in Kew.

Until the early 19th century, Glycine frutescens was the unrivalled pride of collectors of exotic plants. That changed in 1816.

A Rival from China

John Reeves (1774–1856) had a career in tea. In 1812, he was sent to China by the British East India Company as Chief Inspector of Tea at Canton. But he was not solely focused on tea—Reeves was also a keen botanist, and Joseph Banks had commissioned him to acquire plants for the Horticultural Society of London.

As a foreigner in China, Reeves was not allowed to travel far into the interior of the country. He could either visit the famous Fa Tee plant market or rely on his Chinese contacts. One such supporter was the merchant Pan Zhangyao (1759–1823), known as ‘Consequa’ to his international customers. Reeves persuaded him to propagate a Glycine sinensis (today Wisteria sinensis) from his garden.

Reeves was very successful in collecting plants and was responsible for introducing many garden species to Britain. The Glycine sinensis he obtained from Pan Zhangyao is the plant commonly seen in British gardens today, celebrated for its sweet fragrance.

A Dangerous Voyage: Shipping Wisterias to End Customers

Finding new plants was the easy part. Getting them safely to Britain was another matter entirely. Plants shipped by sea had to endure darkness, extremes of temperature, saltwater exposure, and vermin. Ship crews often neglected the plants, resenting the space they occupied. Plants fared best when placed above deck to receive sunlight. Plant hunters therefore tried to secure space for them on the poop deck, the highest part of the ship and furthest from sea spray.

To improve the odds of survival, Reeves sent his wisteria plants — and a selection of 100 specimens — on two different ships:

- One set of plants travelled aboard the East India Company merchantman Cuffnells, under Captain Robert Welbank. Welbank had a good reputation for transporting plants, and 90 of 100 plants survived the voyage on the Cuffnells in 1816. The wisteria arrived in Britain on 4 May 1816.

- The second set of plants arrived on 11 May 1816 together with Reeves himself aboard the Warren Hastings under the command of Captain Richard Rawes.

Conquering Gardens and Hearts

Reeves’s wisteria sinensis plants made their way into several British gardens by propagation, and became a product for sale in garden nurseries from about 1820:

- Captain Robert Welbank gave the plant he had transported to his brother-in-law, Charles Hampden Turner of Rooksnest Park, Surrey — a botanist and Geological Society member. The wisteria flowered in 1819. Turner received a medal from the Horticultural Society for his successful endeavour. One wonders, though, if the plant would have agreed to this award, as Turner kept it in a pot, first in his peach house, infested with the vermin red spider, and then in a cool and shady greenhouse. The plant bravely survived, and was still knowen to be in the garden in 1835.

- Cuttings were shared by Turner with the nurseryman Loddiges of Hackney and the Horticultural Society. Loddiges offered wisterias for sale around 1823.

- Captain Richard Rawes gave the plant to Thomas Carey Palmer of Vale Cottage, Bromley.

- Early propagations were soon planted at the Horticultural Society’s garden in Chiswick and the Royal Gardens at Kew.

- Palmer also gave a cutting to Amelia Hannah Long, Lady Farnborough (1772–1837), of Bromley Hill. In her days she was well known as a skilled horticulturist, and a talented watercolour painter. She grew the wisteria “beautifully trained over an umbrella-shaped ironwork frame”.

- Another part of Palmer’s plant was given to the nurseryman Lee of Hammersmith around 1818.

From the Gentleman’s Gardens to the Cottages

When Lee of Hammersmith first offered wisterias for sale, the price was a staggering six guineas — equivalent to 40 days’ wages for a skilled tradesman. Still, Sir James Edward Smith, founder of the Linnean Society, bought one in 1821.

By 1826, every collector of exotic plants worth their salt had a Wisteria sinensis. It was a firm part of a gentleman’s garden. However, as Joseph Sabine noted in 1826, the plant was not yet generally known or seen as an ornament for farmhouses, cottages, or park lodges. By 1838, the price had fallen to a more accessible 3–6 shillings. By 1872, Wisteria sinensis had become a common climber in British gardens.

Naming the Plant

It took time for botanists to agree on a final scientific name:

- Catesby’s plant was known as the ‘Carolina Kidney Bean’ or ‘Catesby’s climber’ in early nursery catalogues around 1724.

- In 1753, Linnaeus named it Glycine frutescens L.

- The genus Wisteria was established by Thomas Nuttall in 1817/1818.

- Shortly thereafter, French botanist Jean Louis Marie Poiret validly transferred Glycine frutescens into the genus Wisteria, resulting in Wisteria frutescens (1823). Today, the World Flora Online (WFO) plant list recognises both Wisteria Nutt. and Wisteria frutescens (L.) Poir.

- With the introduction of the genus wisteria the Glycine sinsenis became a wisteria sinensis.

Conclusion: the Time Line Matters

Jane Austen wouldn’t have known a wisteria, but she might have encountered Glycine frutescens. With the right connections to gentleman or lady botanists, it’s possible she saw this North American plant in a garden. However, she would not have enjoyed the sweet fragrance of Wisteria sinensis, which first flowered in Britain in 1819 — two years after her death.

As for the wisteria in Bridgerton: it is historically plausible to feature Wisteria frutescens in the gardens of aristocrats. As for Wisteria sinensis, we have seen that was for sale in garden nurseries from about 1820, at high cost. Thus, it was a plant available for the rich. However, given the slow growth of the plant, it is unlikely that it would have covered an entire country estate façade during the Regency era as seen at the front of Bridgerton House.

Related posts

Sources

Julia Blakely: “What’s in a Name? The Related Talents of Mark Catesby and Gertrude Jekyll”; at: https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2015/06/22/whats-in-a-name-the-related-talents-of-mark-catesby-and-gertrude-jekyll/, June 22, 2015

Val Bourne: Growing And Pruning Wisteria; at: https://www.hopesgrovenurseries.co.uk/blog/growing-and-pruning-wisteria/ , 15th April 2023

Colin Mills (compiler): Wisteria sinensis (Sims) Sweet; at: Hortus Camdenensis, Dec 23, 2009, https://hortuscamden.com/plants/view/wisteria-sinensis-sims-sweet

John Damper Parks’ journal and notes: Copy of a letter from John Parks [to Joseph Sabine, secretary of the Horticultural Society of London], Pages 12-13, Date: 7 May 1824; at: https://collections.rhs.org.uk/view/80344/pages-12-13-of-john-damper-parks-journal-and-notes-copy-of-a-letter-from-john-parks-to-joseph-sabine-secretary-of-the-horticultural-society-of-london?q=must,any,contains,Don%20Journal&offset=3&limit=12

Dr David Marsh: “The Garden History Blog: Wisteria”; at: https://thegardenhistory.blog/2014/08/02/wisteria/, 02/08/2014

Frederic D. Grant, Jr.: The failure of the Li-Ch’uan Hong: Litigation as a hazard of 19th century foreign trade; http://www.grantboston.com/Articles/Lichuan.pdf

International Dendrology Society “Wisteria sinensis (Sims) Sw”; at Trees and Shrubs Online: https://www.treesandshrubsonline.org/articles/wisteria/wisteria-sinensis/

Dr James Compton: “The first Wisteria sinensis in Europe” at https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/crg/the-first-wisteria-sinensis-in-europe/ ; Culham Research Grope, University of Reading, March 10, 2015.

James A. Compton: A Vignette of Botany in the Age of Enlightenment: The Story of Catesby’s Climber or the Carolina Kidney Bean Tree, Wisteria Frutescens; 2015, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine

James A. Compton: “815. Wisteria Sinensis on the Slow Boat from China: The Journey of Wisteria to England“; Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. 32 (3–4): 248–293, 28 October 2015.

John Grimshaw: The Reeves connection; at John Grimshaw’s Garden Diary, 2009, https://johngrimshawsgardendiary.blogspot.com/2009/12/reeves-connection.html

Ciel Haviland, Transporting Plants between India and England; at: The Gwillim Project: https://thegwillimproject.com/natural-history/botany/transporting-plants-between-india-and-england/

Joseph Sabine, Esqu., On Glycine Sinensis; Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London , 20.6. 1826: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/155316#page/489/mode/1up

“Captain Robert Welbank”; at Welbank family genealogy pages, maintained by Paul Welbank: http://welbank.net/tng/getperson.php?personID=I474&tree=tree1

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)