In this post:

The rose is the national flower of England. It is, however, not the rose we know today that became the symbol of the country. The English rose – rosa gallica officinalis –was, roughly said, a wild rose. It was very popular in British gardens of the 18th century, as its fruits could be used as tea, marmalade, or as medicine (thus the alternative name apothecary’s rose).

It was only from the mid-18th century that natural philosophers and gardeners began to experiment with new varieties of roses that had been introduced from other countries. By the end of the 18th century, cultivated roses had spread throughout Europe, and with it a new enthusiasm for this beautiful flower.

At the time of the pioneering voyages of James Cook and Joseph Banks, the enthusiasm for exotic plants met with an increasing interest in science and the possibility to travel onboard ships of the navy or the East India Company to foreign continents. Many gentlemen and tradesmen became instrumental in providing botanists and cultivators with new plants for experiment, hobby and business.

When we say ‘experiment’, we have to keep in mind that genes and chromosomes were not yet known. Even the concept of pollination by insects or human hand was only vaguely understood. To create new variaties, the common practice was to plant roses closely together and to hope for the best.

These men and women were among the first in the 18th century to help cultivating new variaties of the rose:

A Lady’s Rose

Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland (1715 –1785) is credited with introducing the Portland rose to England from her Grand Tour on the continent around 1775. The Portland rose actually was a rose from Paestum / Italy, a cross between the rosa gallica and the rosa damascena, growing between the ruins of Paestum. It became known as ‘Scarlet Four Seasons’ Rose‘, and was the parent of the whole class of about 84 Portland roses (of which only about 12 still exist today) that were developed from it.

The Duchess of Portland was a keen botanist, a very intelligent woman and an avid collector. She also botanised in the Peak District in 1766.

The East India Connection

Scotsman William Roxburgh (1751 – 1815) was a surgeon’s mate on an East India Company ship in 1772 and thus came to India. As he also was a botanist, he worked extensively in India, described species, conducted economic botany experiments and published numerous works on Indian botany. He took charge of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens from 1793. Roxburgh sent many Indian seeds and plants home. It was him who introduced seeds of the rosa indica odorissima to the Humes, leading British amateur botanists in Herefordshire (more about them in a minute).

East India Company director Gilbert Slater gave his name to a recurrent red rose he received from China in 1791. He quickly introduced the new variation of the rose with its striking crimson colour to the British market. It became an immediate success, and as “Slater’s Crimson” soon was taken to gardens in e.g. France and Italy.

Amateurs – a Class of Its Own

Sir Abraham Hume, 2nd Baronet (1749 –1838), his wife Amelia (1751 – 1809) and their head gardener James Mean cultivated many exotic plants from India and the East Indies in their garden at Wormleybury / Hertfordshire between 1785 and 1825. Though being amateurs, they were very skilled: James Mean also edited guidebooks for gardeners and addressed the Horticultural Society of London. Many exotic plant where first cultivated by the Humes, even if it took time to succeed. When the Humes received seeds from the rosa indica odorissima in 1796, it bloomed for the first time in 1799. The rose became known under the names ‘Hume’s Blush Tea-scented China‘, ‘Sweet-scented China-Rose‘, ‘Odeur de Thé Rose’.

The Humes were well connected in Europe: They contributed to Empress Josephine’s large collection of roses at Malmaison despite the war between Britain and France.

The Chinese Key of Heaven

In 1794, George Macartney, 1. Earl Macartney (1737 – 1806) returned from the unsuccessful mission to open China for the British market. However, he brought with him a rose from China that became known as the Macartney-Rose, or rosa bracteate. It is rather unruly, and has extremely sharp and strong thorns. This might explain why it became the parent for only one rose we know today, the yellow ‘Mermaid’.

Bringing roses from China didn’t actually take much exploring. Roses were immensely popular in China. The famous Fa Tee gardens were a nursey that grew them in large amounts and varieties. These roses weren’t wild roses but cultivated roses. They became known as tea roses, as their leaves are supposed to smell of black tea. Most travellers simply went to Fa Tee gardens and bought a few species.

- Mr. Lee and Mr. Kennedy sent home the rosa rugosa in 1796. They were gardeners running a nursery in England, and catered, among others, for the Humes.

- Gardener and explorer William Kerr added the white-flowered rosa banksiae in 1807, which he named after the wife of his patron, Joseph Banks.

- A Mr. Thomas Evans brought the cruenta rose with him from China in 1810.

- Charles Francis Greville, Esq., had his ‘Seven Sisters’ rose sent to him from China between 1815 and 1817.

The journey home was the dangerous parts with salty air, storms, pirates and the Napoleonic continental system threatening the safe arrival of the plants.

Dear Regency enthusiast, brief histories of the roses usually state that Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon, kicked-off the craze for the cultivated rose in Europe. She certainly had a large collection of roses (created from 1804-1814) in her garden in Malmaison / France, and influenced many cultivators and botanists. Her patronage made great works such as Pierre-Joseph Redouté’s famous book „Les Roses“ possible. However, let’s not forget that collecting roses is not possible without proper material to collect. Many roses from Josephine’s collection had been collected and developed into new varieties by flower enthusiasts some decades earlier allover the world.

Extended Reading

- Read a guidebook edited by head gardener James Mean: Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener by John Abercrombie and James Mean

- Enjoy P. J. Redouté’s illustrated book “Les Roses”, based on Empress Josephine’s garden.

Note: The roses on the photos are not relating to the roses mentioned in the texts. I have no idea what varieties they are. If you do know it, please feel free to contact me and let me know.

Sources

• Brent C. Dickerson: The Old Rose Advisor, volume 1

• Brent Dickerson: The Old Rose Informant

• Lynne Chapman, Noelene Drage, Di Durston: Tea Roses: Old Roses for Warm Gardens

• Anne Rowe: Hertfordshire Garden History: A Miscellany

• Ernest Wilson: Aristocrats of the Garden

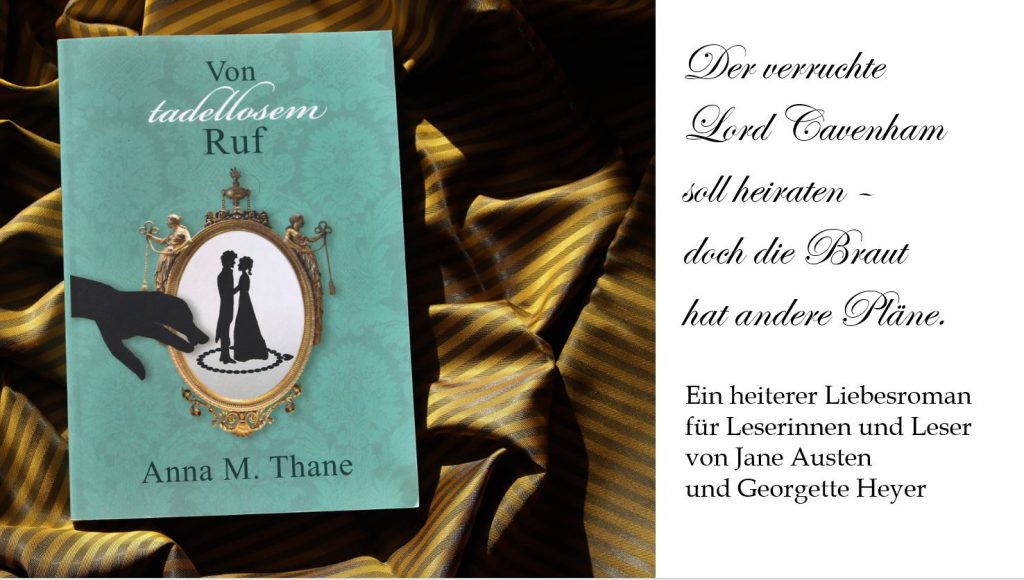

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)