At first glance, 18th century shoes aren’t very different from today’s shoes – though they are, of course, more delicate and ornate. At a closer look however, many features of shoes we take for granted today were invented only after 1830. Enjoy some amazing facts about shoes, shoemaking, and photos of lovely shoes.

At first glance, 18th century shoes aren’t very different from today’s shoes – though they are, of course, more delicate and ornate. At a closer look however, many features of shoes we take for granted today were invented only after 1830. Enjoy some amazing facts about shoes, shoemaking, and photos of lovely shoes.

Six amazing facts about shoes

- For most part of the 18th century, shoes were fastened with buckles

- Shoestrings as we know them today, i.e. strings with aglets laced through shoe holes and then tied, were patented in England in 1790.

- In 1814, mechanically made shoes for soldiers cost 9 s 6 d a pair (about 3 daily wages of a skilled tradesman). Half boots could be bought for 12 s. The freshly invented Wellington boot was available for 20 s.

- Producing different shoes for right and left feet started around 1830 in France. In these first attempts, little paper labels on the insoles of the shoes indicated left and right. However, the shoes were still made on straight lasts with no differentiation between the left and right foot. By the end of the 19th century, producing left and right shoes had become common as shoemakers then worked with combinations of sole and vamp cuts tailored to fit either the right or the left foot.

- The first steps towards the mechanisation of shoemaking were taken during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1810, engineer Marc Brunel developed a machinery that could mass-produce nailed boots for the soldiers of the British Army. But after the end of the war in 1815, manual labour became cheap, and the demand for military shoes declined. Thus, Brunel’s shoe manufactory ceased business (read more about it here).

- The industrialization of shoemaking began around 1830.

Types of shoes in the 18th century

Here is a – limited – selection of 18th century shoes for you to enjoy:

High heels

During the 16th century, royalty started wearing high-heeled shoes, probably to look taller and more impressive. In 17th century France, heels were exclusively worn by aristocracy; red heels were reserved for the King and his royal court.

As usually, fashion from the French courts became popular across the Channel. The red heel came into vogue in England and remained so until well into the 18th century.

A person with authority or wealth was often referred to as ‘well-heeled’.

with silk embroidery; heels: 8 cm

decorated with silver plated Lyonese thread; heels: 8 cm

with gold colored threads and pink ribbon;

heels: 8,2 cm

green leather and raspberry colored ribbons, metal threads and red glitter

From the 1780s through the 1790s, the height of heels gradually decreased. During the French Revolution excesses such as aristocratic fashion was seen with increasing disdain.

owned by Queen Therese of Bavaria

Pattens

In former times, streets were bad and extremely dirty. To protect the shoes from mud or horse dung it became common from the 17th century to wear so called pattens. Pattens consisted of a wooden sole with metal plates nailed to it. Another metal piece made contact with the ground. A patten’s platform could be as high as 7 centimeters. In the 18th century, pattens were mainly worn by women and working-class men in outdoor occupations. In houses, pattens were taken off upon entering to not to bring dirt inside. Wearing of pattens inside church was discouraged, probably because of the noise they made.

iron nails adjustable to individual size

leather and red velvet

Mules

In the 18th century salon mules were shoes for upper-class women. The trend is said to have been started by Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV of France. Thus, wearing salon mules was erotically charged.

The forerunner of the mule was the chopine.

Buckled shoes

For most part of the 18th century, shoes were fastened with buckles. Shoe buckles were worn by men and women alike from the mid-17th century through the 18th century. The buckles were made of, e.g., brass, steel, or silver, and set with diamonds, quartz or imitation jewels.

Tied shoes

In medieval footwear we see shoelaces passing through hooks or eyelets that are placed either down the front or the side of the shoe. In the 16th and 17th century, shoes were usually tied with ribbons.

Shoestrings, i.e. strings laced through shoe holes and then tied, were invented by Harvey Kennedy who took out a patent on them in 1790. The new thing was that he added a new feature: the aglet. Aglets keep the fibres of the cord from unraveling; and make it easier to feed the cord through the shoe holes.

colors: pomegranate green and pink

shoes marked right and left

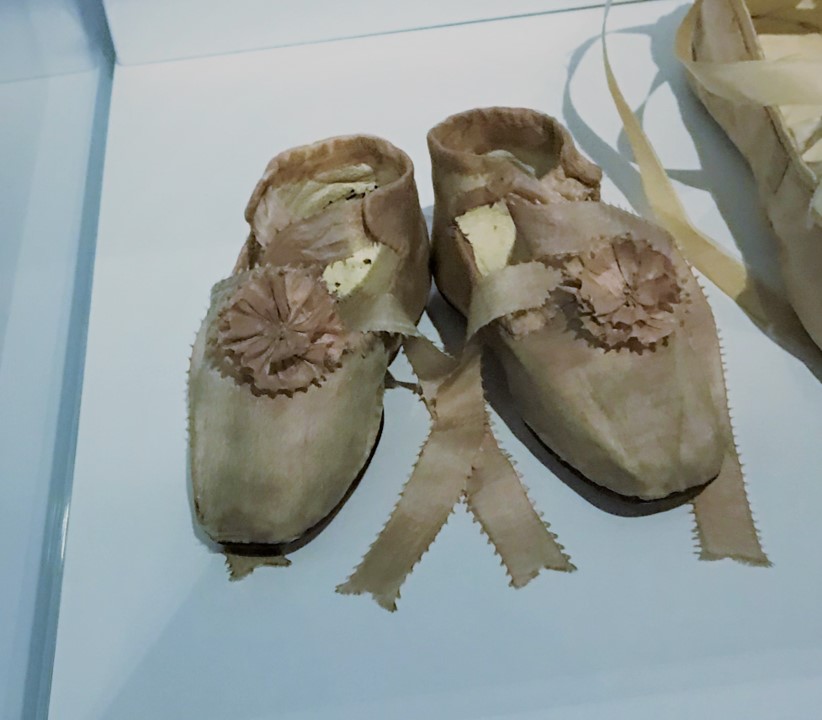

Baby shoes and children’s shoes

Baby shoes have always been cute. In the early 18th century, they were made of cotton. Children shoes of the upper class were often made of silk or silk satin.

right: around 1780, colored silk with pink ribbons

Military shoes

Right: 1806 light cavalry boots, complete with silver tassels

Middle: shoes of French infantry soldiers, 1780

Right: shoes to wear with a gala uniform, 1804

Related articles

Sources

- “Ready to go! Shoe-motion“; exhibition at City Museum Munich, St.-Jakobs-Platz 1, 80331 Munich, Germany

- Musée de L’Émperie , Montée du Puech, 13300 Salon-de-Provence , France

- V&A Museum, Cromwell Rd, Knightsbridge, London SW7 2RL, UK

- www.wikipedia.com

- www.starlinkmachinery.com: Shoe machines, out with the old, in with the new; 2016

- Bellis, Mary. “The History of Shoes.” ThoughtCo, Feb. 11, 2020, thoughtco.com/history-of-shoes-1992405.

- “Timeline: A History of Shoes”. Victoria & Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/shoestimeline/

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)