This beautiful gala dress-suit was made in the seconded half of the 18th century. Enjoy some pictures of a truly splendid garment and read more about its owner: an Italian aristocrat with liberal ideas and close links to Napoleon.

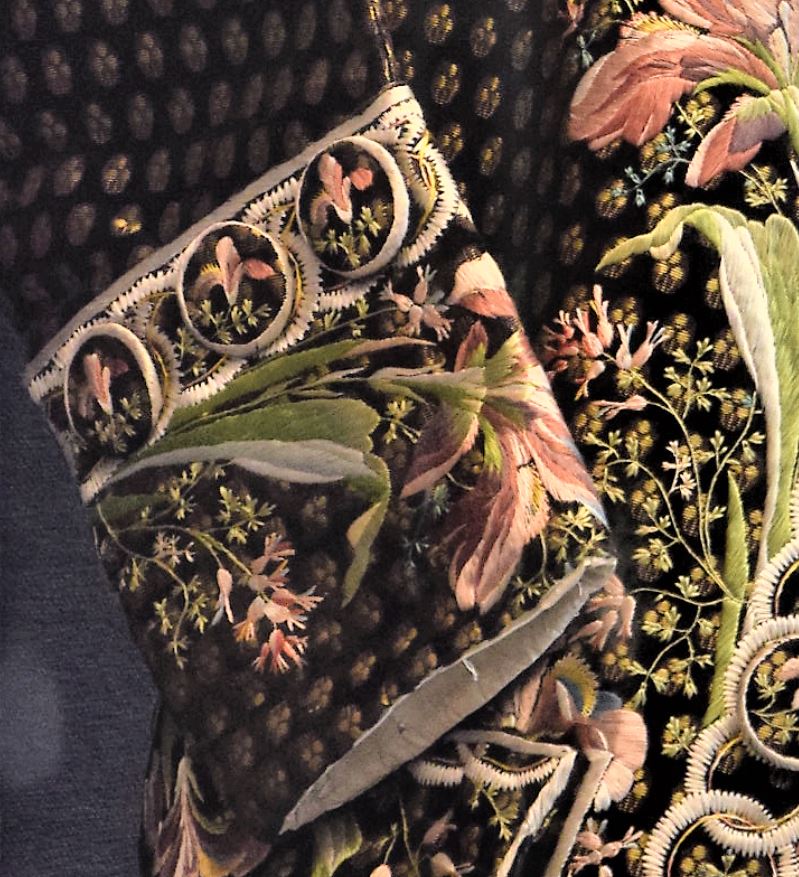

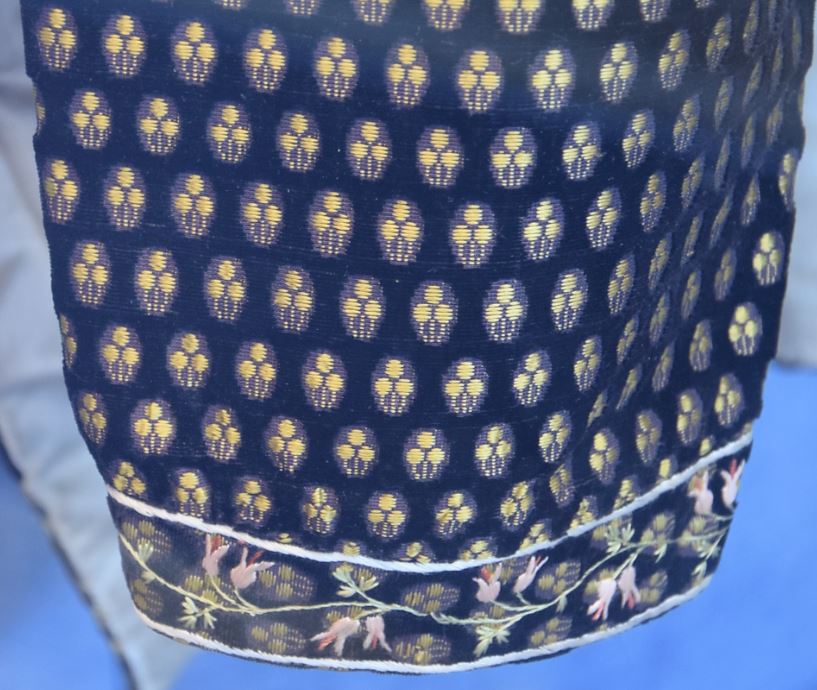

The costume features tails with fitting sleeves and coloured embroidery in silk thread-painting.

The silk uses for the embroidery is probably Italian, as Italy was one the main silk producers of the 18th century. The fabric of the gala dress-suit is textured velvet, the tailoring is Venetian.

The gala dress-suit was worn with breeches and a waistcoat. The breeches were fastened at the knee with a belt-band.

The cream coloured waistcoat is made of silk grosgrain, which is a heavy, stromg fabric often used for waistcoats, jackets, petticoats, beeches, sleeves, etc. It was cheaper than fine-woven silk. The use of silk grosgrain may indicate that the aristocratic owner wasn’t always as affluent as a gentleman would wish to be.

The striking embroidery of both the coat and the waistcoat depicts mainly irises. The iris is the symbol of wisdom and hope – befitting for a man appreciating the ideas of the enlightenment.

Who was the owner of this lavishly embroidered garment?

The gala dress-suit belonged to Francesco Melzi d’Eril (1753 – 1816), a member of a prominent aristocratic family of Lombardy / Italy.

The liberal aristocrat who liked England

He was a politician with liberal ideas. In 1787, Melzi d’Eril travelled to England and stayed there for nearly a year, mainly in London. He also travelled to Northern England and Scotland, and he stopped in Oxford to study the university system. Melzi d’Eril was interested in the arts, the progress of agriculture, factories, and political institutions. England appeared to him as an ideal model in the economic field but also in politics. He praised the English constitution “because she is perhaps the only modern one who has been able to preserve in large part the civil liberty which is the basis and principle of every great human thing.”

Navigating between republican ideals and the reality of government

Back in Lombardy, he supported the liberal republican ideas of the 1790ies, being dissatisfied with the Austrian rule. When the French army occupied Milan in 1796, Melzi d’Eril offered the ceremonial keys of the city to Napoleon. However, Melzi d’Eril soon became disillusioned by the new rulers – not least maybe because he was taken hostage for about 3 months in 1796. Nevertheless, he played an important role in the development of the Napoleonic Italian Republic (1802–1805), serving as vice-president under president Napoleon. However, Melzi d’Eril soon had to learn that Napoleon was rather authoritarian. Republican ideals turned out to be unworkably. In 1805, Italy was proclaimed a Kingdom. Thus, any chances for a new, more liberal, constitution vanished.

There was more disillusionment in store for Melzi d’Eril: After all the years of service, Napoleon did not make him his viceroy in 1805. He appointed his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais instead. Thus, Melzi d’Eril found himself politically marginalized. He attended the celebrations for the coronation of Napoleon as king of Italy, but immediately afterwards he left Milan for Bellagio at the Lake of Como.

Friend and critic of Napoleon

Napoleon and Melzi d’Eril were friends, but Melzi d’Eril was disappointed by Napoleon becoming more and more authoritarian. He became a frank critic of the Napoleonic rule. Over the years, tiredness, disillusionment and intrigues against him by members of Napoleon’s family took their toll: Melzi d’Eril grew more and more determined to lay down the burden of politics. This, however, wasn’t so easy.

In 1807 Napoleon conferred the title of Duke of Lodi to make Melzi d’Eril, a title reminiscent of the Battle of Lodi (10 May 1796) fought between the French and Austrian forces. It came with a rich prerogative of 200,000 lire per year. Additionally, during the absences from Milan of viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais, Melzi d’Eril assumed the presidency of the Council of Ministers and effectively acted as head of the government, keeping Napoleon and de Beauharnais informed of everything.

After Napoleon’s abdication in 1814 and an uprising in Milan a couple of days later, de Beauharnais left Milan for good. The city fell under the Austrian rule again. Melzi d’Eril avoided direct confrontation with the Austrian government but also refused to bow to the new rulers. He died in 1816.

Sources

- Carlo Capra: MELZI D’ERIL, Francesco, in: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 73 (2009): https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-melzi-d-eril_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

- Villa di Melzi, Napoleonic Museum, Bellagio / Como, Italy

Related articles

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)