The painter Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) was t-h-e female celebrity artist of the 18th century. In the story-telling about her career start, men play a vital role: as key events for her recognition as a serious artist in Britain are considered the patronage by the painter Joshua Reynold, and celebrity actor David Garrick sitting for a portrait that caused a stir in the art world. I don’t aim to minimize the influence of male clients, colleagues and patrons on Angelica Kauffmann’s success. However, in this article, I highlight the role of female sponsorship and cooperation during her career in London (1766 – 1781), as it shows how women supported each other in a world that belonged to men.

Lady Wentworth gives a helping hand

For male British Grand Tourists, Angelica Kauffman was one of the attractions of Rome. She belonged to the international set of artists that catered to the needs of the travelling aristocrats. Posing with the remnants of antiquity for the charming Angelica became a must-do when visiting the city in the years from 1763 to 1765. Though noble clients like John Parker (the future Lord Boringdon), Lord Exeter, John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer, etc helped to spread the artist’s fame by taking the portraits home, it actually was a woman who took Angelica’s career to the next step.

Angelica met her first female patron, Bridget Wentworth, in Venice in October 1765. Lady Wentworth was a British resident in Venice, her husband being the British envoy to the republic. She was known for her salons, and it was there that Angelica met her. Lady Wentworth was charmed by the artist and her work. She could clearly envision a bright future for Angelica in London. She took her under her wings, and showed her how to move in High Society. In 1766, Lady Wentworth finally managed to persuade Angelica to go to Britain and to lodge with her in Charles Street in noble Mayfair until Angelica was settled. Lady Wentworth also helped Angelica to find her first studio, by recommending her to good acquaintances who indeed rented rooms to Angelica in their house.

Angelica wrote to her father:

I am in a private house with excellent people, old acquaintances of my Lady, who has had the goodness to recommend me to them as if I were her own daughter. (…) The people of the house do everything for me, the handywoman is a mother to me, and the two daughters love me as a sister. (…) I have four rooms, one where I paint, the other to show my portraits which are finished.

Having a location to display the paintings and to received sitters was vital for an artist in London. Angelica soon had the pleasure to see the finest ladies of High Society in her studio. “My portrait are snapped up by everyone”, she wrote to her father. Her start into the British art world couldn’t have been smoother.

Enter the queen

Angelica was busy painting and networking for a couple of months when in early 1767 her life was graced by royal acknowledgment. The Duchess of Ancaster, a lady-in-waiting to Queen Charlotte, came to Angelica’s studio to see her work. And shortly after, no one less than Princess Augusta, sister of George III, visited. Angelica was in raptures: “O never, has any painter received such a distinguished visitor.“

It didn’t take long until Angelica was presented to the Queen. She painted her portrait in the same year. It was regarded as a sensation, as it showed the Queen in her role as mother and patron of the arts. The painting – as an engraving – quickly became a part of many noble living-rooms, spreading the message that art bloomed in Britain thanks to her Majesty the Queen. In other words: Angelica had managed to make the Queen look really cool.

Queen Charlotte and Angelica got along very well and even became friends, as Angelica’s biographers suggested. Indeed, it was the Queen who lobbied for the admission of Angelica Kauffman as a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768.

Apparently, she also took an interest in the artist’s private affairs. Here are two stories that shine a light on the relationship between Queen and artist:

- Angelica’s biographer noted that the Queen put in a good word for the younger brother of Angelica’s main engraver, William Wynne Ryland (engraver to the King). This young man, Richard, was a good-for-nothing. When he was arrested for theft and was even sentenced to death, William exercised all the influence he possessed at Court to save his brother. He even persuaded Angelica to add her influence and bring his request before Queen Charlotte. As a matter of fact, the Royal pardon was granted to Richard.

- Allegedly, the Queen was the only person Angelica told about her marriage plans that she had kept secret from her family. She wondered whether she should marry Count de Horn who courted her in 1767, and the Queen encouraged her to do so. When it turned out that the Count was an imposter, and Angelica’s reputation was in danger of being tainted, Queen Charlotte remained on Angelica’s side. Some rumours even have it that she exercised her influence even further: just in time, certain letters reached Angelica, proving that de Horn was not only a fraud, but also a bigamist, thus making an annulation of the marriage possible. Wether the Queen really had a hand in this affair, will never be known.

A supportive soulmate: Theresa Parker

There was more to Theresa Parker, (née Robinson (1745 –1775)) then being the second wife of a nobleman. She was a designer and art patron. In Angelica, she saw more than a portraitist. Actually, Theresa was the first woman to fully appreciate Angelica’s ambitious project: history paintings. Together with her husband, Lord Boringdon (who had his portrait painted by Angelica in Italy), she bought the ground-breaking history paintings Angelica had created for the opening exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1769 for her home, Saltram House.

Theresa and Angelica were a new type of females: they belong to the intellectual avantgarde. Theresa deeply understood the topics Angelica chose for her works. Greek mythology was popular, but still a rather ‘nerdy’ topic for women. Both Theresa and Angelica shared the love for these stories. About Angelica’s painting “Hector Taking Leave of Andromache”, Theresa wrote in a letter to her brother: ‘The prettiest and I think the best she [Angelica Kauffman] ever did”.

Having Theresa Parker as a patron was an important step in Angelica’s development as a history painter. Theresa encouraged Angelica to paint scenes of British legends, a topic no other painter had yet picked up. Angelica followed the advice and depicted British heroines such as Rowena, Elfrida and Eleanor. Doing so, she kicked-off the trend of the “gothic-picturesque”. Though history paintings were considered a male domain, Angelica succeeded. Her history paintings didn’t dwell on war and blood-shed. They showed the female side of a legend: conflicting emotions, noble virtue or female grief when a hero left for war. These topics endeared her to her female audience.

Bring a friend: a flow of noble female clients

The ladies of High Society flocked to Angelica’s studio. Having a portrait painted by her was popular for several reasons:

- Angelica had excellent manners, so that she was regarded as either a near-equal or an agreeable companion by her noble sitters

- Her studio was perfectly respectable, so that a lady could go there without male escort.

- Last but not least, Angelica made her female sitters look beautiful. She captured the character, and carefully idealised face and body. She was excellent in painting fabrics, and willing to paint her clients in the latest fashion or beautiful costumes of an imagined antiquity. The finished portrait was a mixture of a likeliness and the female ideal of the age, flattering the sitter.

Angelica’s studio became a meeting point, and many noble ladies brought female friends to enjoy the art on display or to watch a good acquaintance sitting for a portrait.

To her female clients belonged Lady Margaret Spencer and her daughters, Lady Elizabeth Berkley, Jane Maxwell (Duchess of Gordon), Anne Loudoun (Lady Henderson of Fordell), Lady Knight, Lady Hester Stanhope, Anne Conway Damer, and the Duchess of Richmond. To all of them, Angelica was a kind of accomplice, painting her clients as beautiful and delicately female as they wished to appear.

Artist sponsoring artists

Angelica held her own salons in London. She wasn’t a person that sought to shine on these occasions, and was pleased best with quiet pleasures. Her soirées were devoted to artistic company. It was important to her to promote brilliance and enjoy its manifestation in others. Her most popular protégée was the painter Maria Cosway, née Hadfield. Allegedly, they had met in the past in Italy, when Maria was still a young girl. Angelica encouraged Maria to refine her already considerable painting skills. In 1779, Angelica assisted her in coming to Britain, and wrote letters of introduction for her entry into society. Once Maria and her mother had arrived in London, Angelica took them under her wings. They lodge with her in Golden Square for a while, and Maria was introduced to useful members of society. She also helped her to participate in academy exhibitions. Maria followed Angelica’s footsteps when the most celebrated female painter of her time returned to Italy in 1781. In recognition of Angelica’s sponsorship, Maria named her daughter after her.

Conclusion: The sisterhood of matrons and artists

The career of Angelica Kauffman highlights the importance of a female network in the art world of the late 18th century. Of course, Angelica wouldn’t have succeeded without the support of male colleagues and patrons. However, her continued success and celebrity status wouldn’t have been possible without her female clients and sponsors. Women were her main clients, as they found Angelica’s art echoed their emotions and desires: Angelica’s portrait made them look like the ideal beauties of the period. Her history paintings gave room to a female view on history and mythology: no gruesome scenes of bloodshed, but scene showing the female side of these stories: grief, conflicting emotions, devotion. It were certainly mainly women who bought the “merchandise articles” related to Angelica’s art: teapots, plates, cameos, prints, etc. The amazing wealth Angelica made from her work in Britain (£14.000, about £1,205,463 in today’s money) is a result of the matronage she could enjoy. Also, her own sponsorship of Maria Cosway helped the artist considerably on her way into High Society, showing once again that women played an important role in ‘making’ a celebrity star.

Related articles

Sources

- Tania Adams, History, myth and portraiture: Angelica Kaufman’s neoclassicism in Britain, posted 26 Jun 2012, Art UK (https://artuk.org/discover/stories/history-myth-and-portraiture-Angelica–Kaufmans-neoclassicism-in-britain)

- Amanda Vickery: “Branding Angelica: Reputation Management in Late 18th Century England, in: Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies Vol. 43 No. 1 (2020)

- Amanda Vickery: Hidden from history: the Royal Academy’s female founders, Royal Academy Magazine, published on 2 June 2016 (https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/ra-magazine-summer-2016-hidden-from-history)

- Victoria Manners, George Charles Williamson: Angelica Kaufman, R.A., her life and her works; Brentano’s, New York, 1900

- Angelica Goodden: Miss Angel: The Art and World of Angelica Kauffman, Eighteenth-Century Icon; Vintage Publishing, 2005

- Gabriele Katz: Angelica Kaufman: Künstlerin und Geschäftsfrau; Belser, 2012

- Heidi A. Strobel: Royal “Matronage” of Women Artists in the Late-18th Century, in: Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Autumn, 2005 – Winter, 2006), pp. 3-9

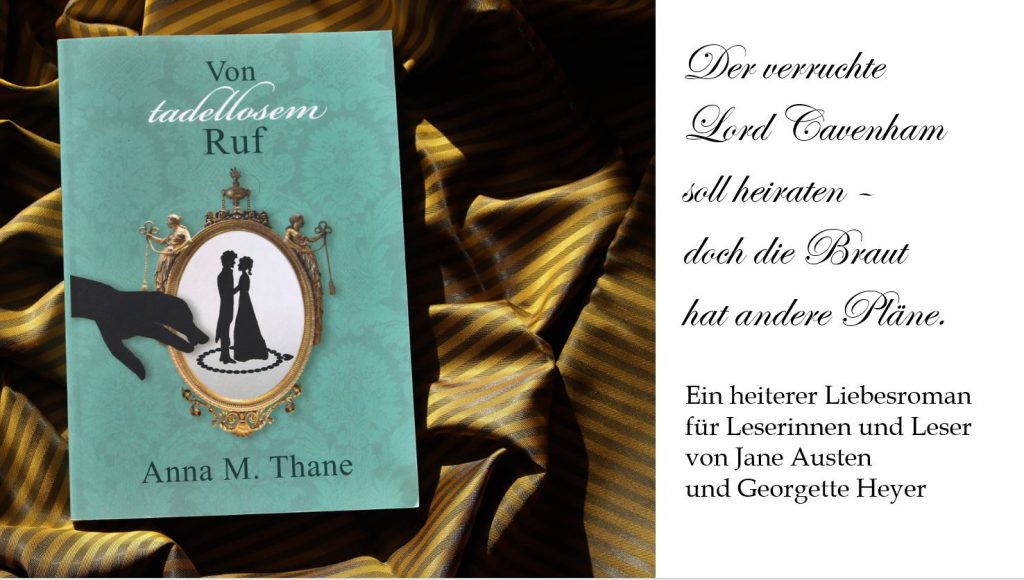

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)

This entry was posted in Exploring the World, The Famed and Famous and tagged Art, Travelling & Exploration, VIP, Writer’s Travel Guide. Bookmark the permalink. Edit