Cut-glass chandeliers were among the most sought-after luxury products of the 18th century. Only the super-rich could afford to buy them. Thus, chandeliers were often designed to match the interior of a room, meaning that they were custom-designed.

Regency Explorer interviews an elegant chandelier from 1815 about the makers, customers, and the influences from fashion, science and politics.

Regency Explorer: You look splendid! Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Chandelier: You are flattering me. I was made in 1815 in London. Unfortunately, it is lost in time which glassmaker created me. I like to believe I was a product of Parker and Perry, the stars of the glassmaker-scene.

Alas, all we know is that Thomas Noel Hill, 2nd Baron Berwick, bought me and two other chandeliers for his elegant home, Attingham Park, and I was placed in the so-called Sultana Room.

Lord Berwick and his wife Sophia were hugely extravagant. They went bankrupt in 1827 and had to sell most of their property. I was lucky: I was excluded from the sales, and so I am still at Attingham Park today.

Regency Explorer: You mentioned the manufacturers Parker and Perry. What were the big names in the chandelier business of the 18th century?

Chandelier: William Parker was one of the first famous British chandelier makers. He was renowned for his glass cutting and manufacturing. You can still see his products in the Bath Assembly Rooms. Beautiful pieces: Lead crystal and silvered brass. Nearly 2,5 m high, slender and elegant. He made them in 1771. When you look at them closely, you will see that he replaced the ball stem with vase-shaped stem pieces. This is believed to be the first use of neoclassical elements for a chandelier, and it also accounts for the slender look.

Parker founded “Parker and Perry” in 1803. This was a loose cooperation with the Perry family, who were brilliant glass manufacturers. In 1817, their partnership became formal. Their chandeliers were famous for the finely double cut pear shaped drops and garland spangles of the highest quality.

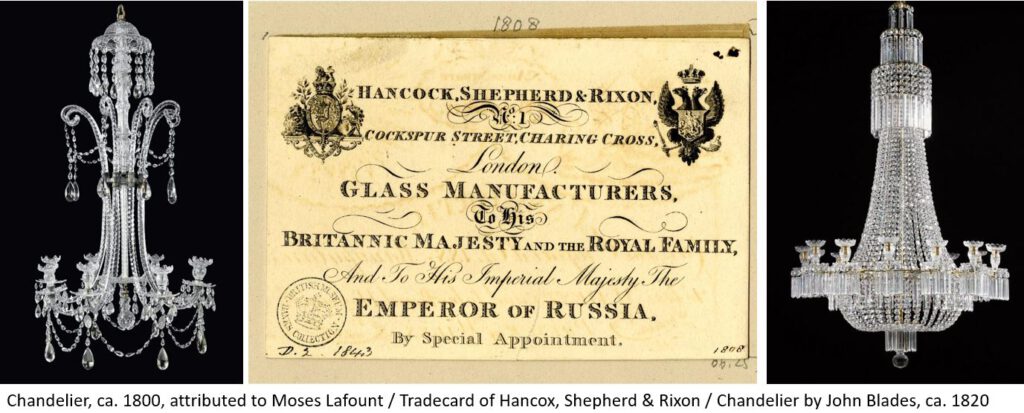

Then, there also was Hancock & Rixon, established in the 1760s.

Moses Lafount was the innovative type: He invented a very elegant new design for chandeliers. The branches were attached to a small brass loop, giving the impression that the entire branch was formed from one long curve of glass. Lafount took out a patent in 1796 for this method.

Another important London glass manufacturer was John Blades, who flourished from around the 1780ies until the 1820ies. Unusually for the period and the business, he employed a designer. This artist (and architect), John Buonarotti Papworth, introduced a number of innovative designs.

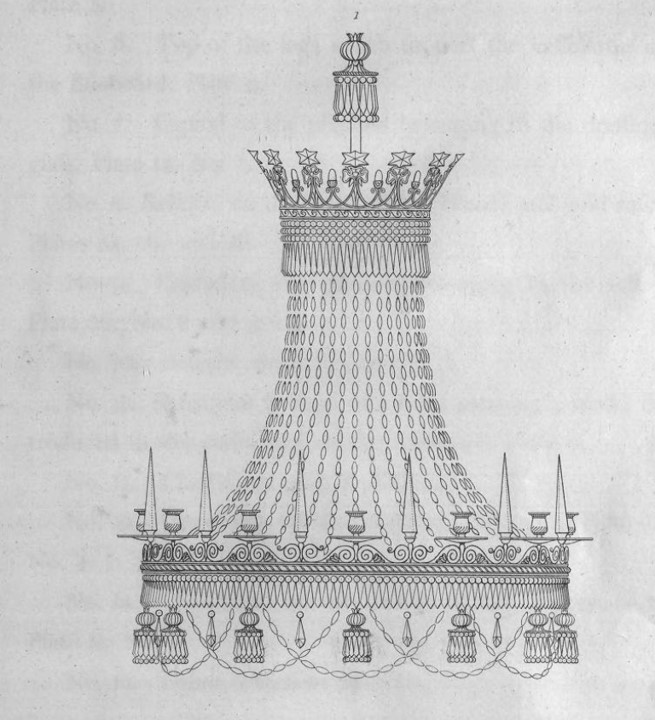

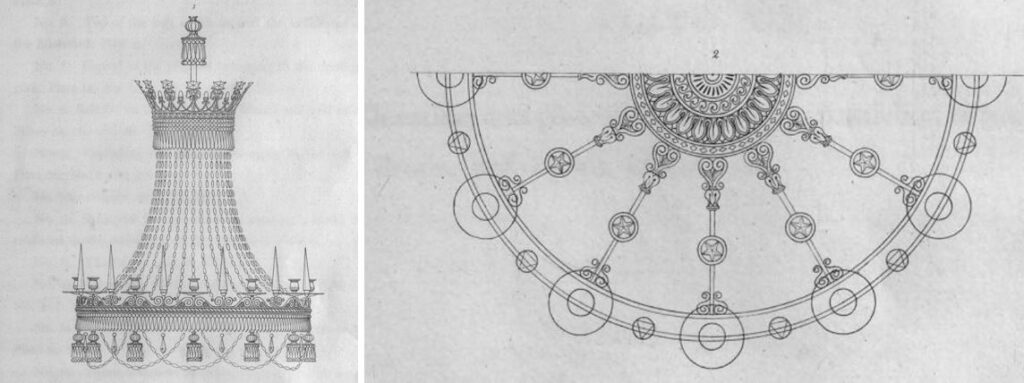

Besides, Thomas Hope (1769-1831), a partner of the bank Hope & Co, designer and collector, left us a catalogue, ‘Household furniture and interior decoration from 1807’, with designs for 2 chandeliers. His work was very influential.

Regency Explorer: Who were the customers? Chandeliers were for the super-rich, right?

Chandelier: Definitively! Parker and Perry enjoyed the patronage of King and Court: George, Prince of Wales, was a very good customer, and so were the Dukes of Devonshire and also William Beckford.

Regency Explorer: … Beckford, the richest commoner in Britain. At the age of ten, he inherited a fortune of £1 million in cash from his father. He spent very much on building and collecting…

Chandelier: There is nothing wrong with it from my point of view. To get back to your question: Hancock & Rixon could print “By Special Appointment To His Britannic Majesty and the Royal Family and His imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Russia” on their invoices from 1814. John Blades’ clients included the Prince Regent and the Shah of Persia.

Regency Explorer: The Prince Regent was a chandelier enthusiast, I dare say.

Chandelier: Absolutely. He commissioned Perry to produce several chandeliers for Carlton House. This included a fifty-six light chandelier, completed in 1808, which was 14 feet high and considered to be one of the finest in Europe. Perry also produced 9 “inverted parasol” chandeliers for the Music Room in Brighton’s Royal Pavilion. Each was shaped like an inverted umbrella, had a painted glass shade, glass beads and featured exotic plants made from bronze or glass.

Regency Explorer: How much would I have to pay for a chandelier in the 18th century?

Chandelier: That would have depended on the size and also on the manufacturer. In 1811, Parker and Perry made a 16 lights lustre, richly mounted in ormolu and ornamented with paste spangles and Chinese bells. It was for the Prince Regent, and he paid 470 guineas for it.

Regency Explorer: That would e the wages for 3.133 work days of a skilled tradesman. We could consider it as half a million pounds in today’s money.

Chandelier: The set of 9 chinoiserie chandeliers for the Music Room of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton I had mentioned earlier cost £4.290.

Regency Explorer: So, about £470 would be a usual price for a regular sized chandelier made by Perry. What about the larger ones?

Chandelier: Well, there was a glass lustre made by Parker & Perry – also for the Royal Pavilion, but for the saloon. This superb piece had 28 lamps and branches and cost £950. It went with an added top of cut glass which cost an additional £150.

Regency Explorer: … a skilled tradesman would have to work for 7333 days to be able to buy it. It would cost about 1 million pound in today’s money.

Chandelier: Impressive, for sure.

Regency Explorer: There were several trends for furniture in the long 18th century. Did these have an impact on the way chandeliers were designed?

Chandelier: Of course, fashions for furniture influenced the style of chandeliers. The Rococo style with elaborate decorative drops and spirals spread in the second half of the 18th century. Robert Adam added the Neo-classical design with classic urns and tapered spires.

Then, there were changes that were brought about to cut costs: Glass-arm chandeliers were made from crystal components. That was expensive. So, around 1790 manufacturers came up with the idea to have a metal frame with candles fixed into ormolu holders attached to the frame. Then, they would use crystal drops cut from broken pieces of glass – recycling, if would like. The crystal drops were strung together in chains in multiple swags and hung from the top of the chandelier. Imagine it to look like a “tent” shape. Additional chains of drops were suspended from the bottom of the frame, they created a “bag” shape. That’s why this chandelier style became known as the tent-and-bag chandelier. The style emerged in England and spread quickly to the Continent and became super-fashionable in France.

The tent-and-bag chandelier went through several variation. Around 1810, the pear-shaped drops were replaced by long slender icicle drops These would be arranged in concentric circles, filling the entire base of the chandelier. It would look like a waterfall.

Regency Explorer: You mentioned the need to cut cost. What were the reasons why production cost rose?

Chandelier: Politics came up with the Glass Excise Act in 1745. It taxed materials for making glass according to the weight of materials used by the manufacturer. Flint glass and white glass were charged at the highest rates, but generally, all kinds of glass were taxed – from windows and bottle glasses to chandeliers. The tax created a significant barrier to the expansion for the British glass industry. It is thus of little surprise that glass makers outsourced glass production to other countries, such as Ireland.

Regency Explorer: Didn’t glassmakers stand up against the Act?

Chandelier: They did. Glass manufactures campaigned determinedly against the Act. As a result, when the Act was amended, the excise duty was changed to apply to the finished glass goods, rather than the raw materials. It did not help much. The excise was amended again in 1825, and then, the rates were raised and onerous new administrative requirements were added. It seriously inhibited the glass manufactures’ ability to compete with Continental glass makers. What’s more, charges on raw materials were back.

Regency Explorer: That doesn’t sound good at all for glassmakers.

Chandelier: The glassmaking industry suffered seriously, but it took Parliament until 1845 to repeal the Glass Excise.

Regency Explorer: Did scientific progress have an impact on the chandelier?

Chandelier: For a long time, Britain had to import quality glass form the Continent, especially Venice, Holland and France. There were efforts to improve British glass making. An important step was the use of coal instead of wood for the glass ovens. And then came George Ravenscroft. He is usually credited with inventing flint glass in 1674. Flint glass is a clear lead crystal glass. I am not so sure that he actually invented the glass. You see: he was a glass merchant, not a craftsman. In any case, Ravenscroft took a patent and established his right to be sole manufacturer of lead crystal glass in England.

Regency Explorer: Hang on, if he didn’t invent flint glass, who did?

Chandelier: Well, some believe that Ravenscroft learned the technique in Venice, where he did business and also lived for a couple of years. Besides, the process was documented in an Italian book, “L’Arte Vetraria”, by Antonio Neri in 1612. The book was translated into English in 1662. Ravenscroft returned to England from Venice and brought with him the glassmaker John Baptista Da Costa. He also had a capable assistant in Hawley Bishopp, who would have been closer to the production. If you ask me: Ravenscroft was the director and financier of the project, but not actively involved in the physical process of glassmaking.

Regency Explorer: I see. Interesting.

Chandelier: It is, isn’t it! Anyway, as a result of this innovation – by whoever – Britan began producing the highest quality glass chandeliers of the time. By the end of the 17th century, about 30 % of British glass were exported. In 1696, there were 62 glasshouses in Britain, and 22 of them made lead glass that you need for the most beautiful chandeliers.

Regency Explorer: Thank you very much for sharing all the information. We wish you a long and shining life.

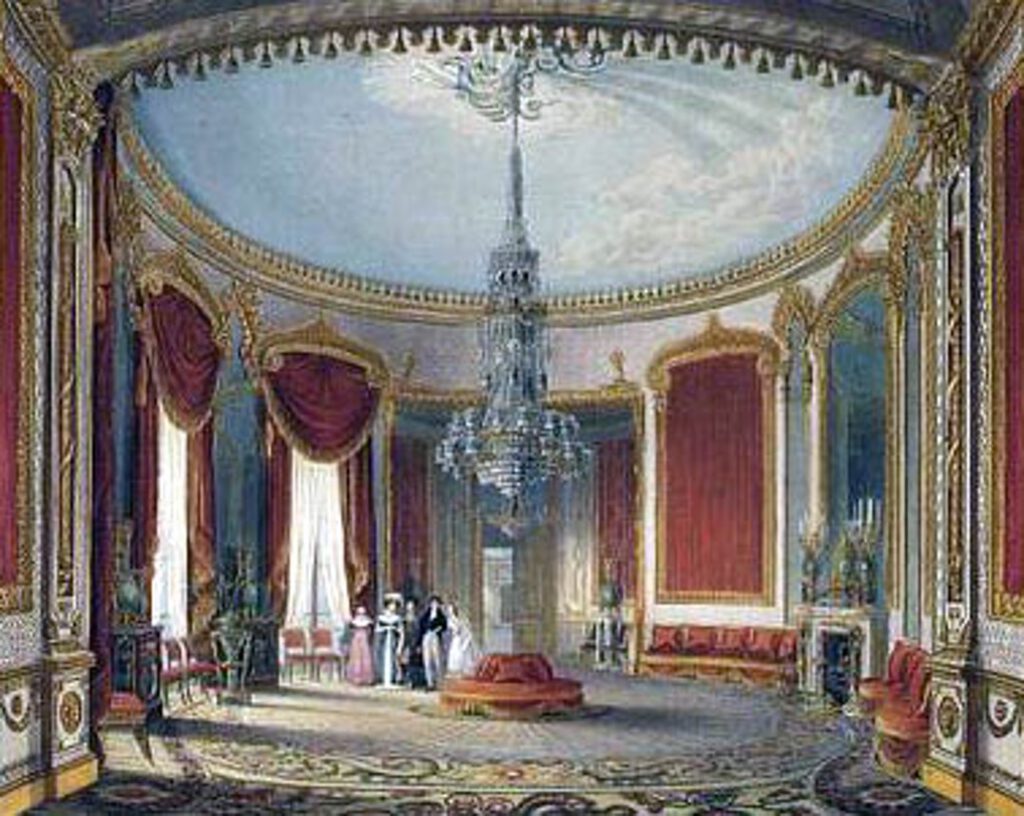

Enjoy here a compilation of photos from chandeliers in British and Continental country houses and palaces.

Related articles

Sources

- “Chandeliers – A Brief History Through Time” by Mallory Custom Lighting, Unit 16, Atlantic Business Park, Hayes Lane, Sully – CF64 5AB, UK (https://mallory-custom-lighting.co.uk/blogs/news/chandeliers-a-brief-history-through-time

- Historic England: “Industrial Heritage -The Glass Industry”, at: https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/education/explorer/teachers-kit-glass-industry-pdf/

- Judith Miller (Ed.): “Lighting” in Antiques Encyclopaedia, Octopus Publishing Group Ltd, 2008

- Kathryn Kane: The Glass Excise and Window Taxes, at: Regency Redingote, 10 October 2008:

- https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2008/10/10/the-glass-excise-and-window-taxes/

- Hope, Thomas: Household furniture and interior decoration, London 1807; Printed by T. Bensley (https://archive.org/details/Householdfurnit00Hope/page/n133/mode/2up)

- Hampton National Historic Site, HAMP 1178, at: https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/hampton/exb/technology/lighting/HAMP1178_chandelier.html

- Dr Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth: A Glassy Society: Glassmaking in 17th and 18th Century Britain https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8yw4iIrMWsI

- Michael Noble: The “Invencon” of Lead Crystal—Or Was It Flint Glass?, Journal of Glass Studies, Vol. 58 (2016), pp. 185-195 (12 pages), Published By: Corning Museum of Glass, 2016 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/90000974)

- Dungworth and C. Brain: Investigation of Late 17th Century Crystal Glass, Centre for Archaeology Report 21/2005 https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/5408/InvestigationofLate17thCenturyCrystalGlass

- Sotheby’s https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/furniture-clocks-works-of-art/a-regency-gilt-bronze-and-cut-glass-fourteen-light

- Christie’s: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6331978

- wikipedia.com

- Royal Collection Trust: https://www.rct.uk/

- British Museum, Great Russell St, London WC1B 3DG, UK

- V & A, Cromwell Rd, London SW7 2RL, UK

- Attingham Park, Atcham, Shrewsbury SY4 4TP, UK

- Saltram House, Plymouth PL7 1UH, UK

- Arlington Court, Arlington, near Barnstaple, Devon, EX31 4LP, UK

- Kingston Lacy, Wimborne BH21 4EA, UK

- Palace of Oberschleissheim, Max-Emanuel-Platz 1 85764 Oberschleißheim, Germany

- Château de Compiègne, Pl. du Général de Gaulle, 60200 Compiègne, France

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)