Art had long been the domain of men. However, from about 1760, women in Britain and France made a splash in painting, engraving and even, sculpturing. Most famous are today the painters Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Angelika Kauffmann, both superstars of their time. However, many more women made careers in the art scene. Let me introduce you to 10 British female artists from all ranks of life.

In the 18th century, women were excluded from academy-based artistic training. Female artists usually grown up in artistic households. They supported the family business. Training and encouragement were provided by fathers, brothers or husbands.

Things started to change in 1759, when British societies for art opened their exhibitions to female artists. Given the chance to exhibit their work in public, women seized the opportunity, even if they had to be content with being labelled as “amateurs” or “honorary” participants. They defied the status an all-male committee gave them by cleverly adding their business addresses in exhibition catalogues. Thus, potential clients knew where to find the professionally active female artist.

Nevertheless, female artists were a rare phenomenon. In 1777, of 190 exhibitors in an exhibition catalogue only 15 were women. Here is a selection 10 short biographies:

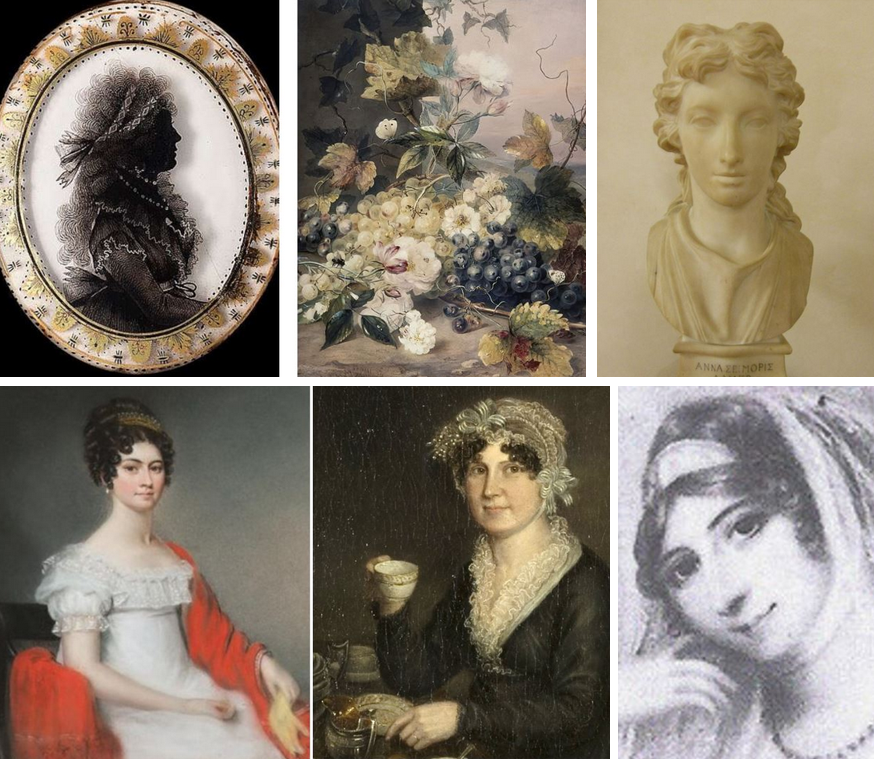

1. Mary Moser: co-founding the Royal Academy of Arts

The daughter (1744 – 1819) of a migrant enameller from Switzerland became a star of the 18th century art-scene. She was especially famous for her depictions of flowers.

Training: by her father, an enameller and drawing master of George III.

- Being old 14 years old, she won a silver medal in the category of ‘Polite Arts’ for her painting

- In 1768, she was a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London – among 32 men and one fellow woman (Angelika Kauffmann)

- The Royal Princess Elizabeth appointed her as her drawing mistress

- In the 1790s, Queen Charlotte commissioned Mary to complete a floral decorative scheme for a room in Frogmore House. She was paid over £900 (or: about 16 years of wages of a skilled tradesman)

Mary ended her professional career when she married, aged 53.

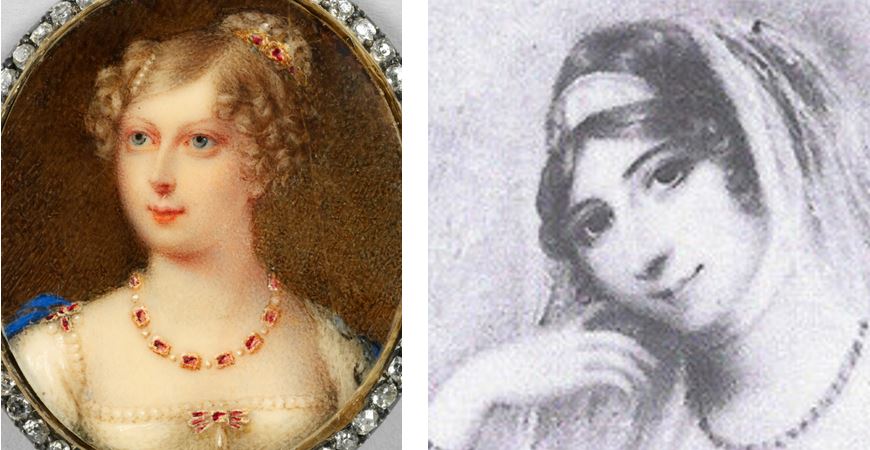

2. Charlotte Jones: portraitist of High Society

The merchant’s daughter (1768 – 1847) from the small but busy port Cley-next-the-sea in Norfolk became the sought-after portraitist of the High Society.

Training: having moved to London after her father’s death, she was trained by Richard Cosway, a famed-famous portrait painter.

- She exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1801 and 1823

- She was appointed “Miniature Painter to the Princess Charlotte of Wales” from 1808 – 1817

- She started her own business in Lower Grosvenor Street in London in 1810

- She was commissioned by Prince William, later William IV, Lady Caroline Lamb and George, Prince of Wales

3. Maria Spilsbury (née Taylor): painting for the Prince

The daughter (1776 – 1820) of an engraver excelled in portraiture, genre painting, and morality painting.

Training: by her father and by Sir William Beecher, a portraitist.

- She began exhibiting at the Royal Academy at the age of 15. From 1792 – 1808, she exhibited 49 paintings

- She had a studio on St. George’s Row, London, where she held private viewing days. These events were so popular that up to twenty carriages could be seen outside

- One of her patrons was George, the Prince of Wales, who frequented her studio. He also commissioned her to paint Patron’s Day at the Seven Churches, Glendalough (1816)

4. Isabella Beetham (née Robinson): from love to fame

Isabella (1750 (?) – 1825) was born into a wealthy family, but when she eloped with the equally well-born Edward Betham (who dreamt of a career as an actor) in the early 1770s, both his and her parents refused to support the couple financially. Defying all odds, Isabella was to become was one of the greatest 18th century silhouette artists.

Training: by John Smart, miniature portraitist

- Isabella contributed to the couple’s income by cutting silhouette images on card and paper, charging half-a-crown for two copies.

- She was the first woman to make a living making silhouettes

- From 1785 to 1809, she had a business on 27 Fleet Street in London, where she painted silhouettes on gold and silver decorated glass, paper, and ivory. She also made miniature portraits for bracelets, lockets, and rings

- Upon her death, her estate was worth £200 ((or: about 3,6 years of wages of a skilled tradesman))

A note for the romantics: The couple had six children. Edward discovered his talent for inventing and became known as the proprietor of the Patent Washing Machine. Isabella and Edward were married until Edward’s death in 1809.

5. Anne Frances Byrne: feeling strongly about misogyny

Anne (1775–1837) was a member of a family of artists. She specialised in birds, fruit and flowers painted in a realistic style.

Training: by her father, William Byrne, an engraver

- Aged 21, she exhibited her first work

- She became a full member of the Royal Watercolour Society in 1809 as the first and only female member of the Society of Watercolour Painters until 1821.

- She withdrew her membership twice as she felt that the appraisal of her work was negatively biased by her sex.

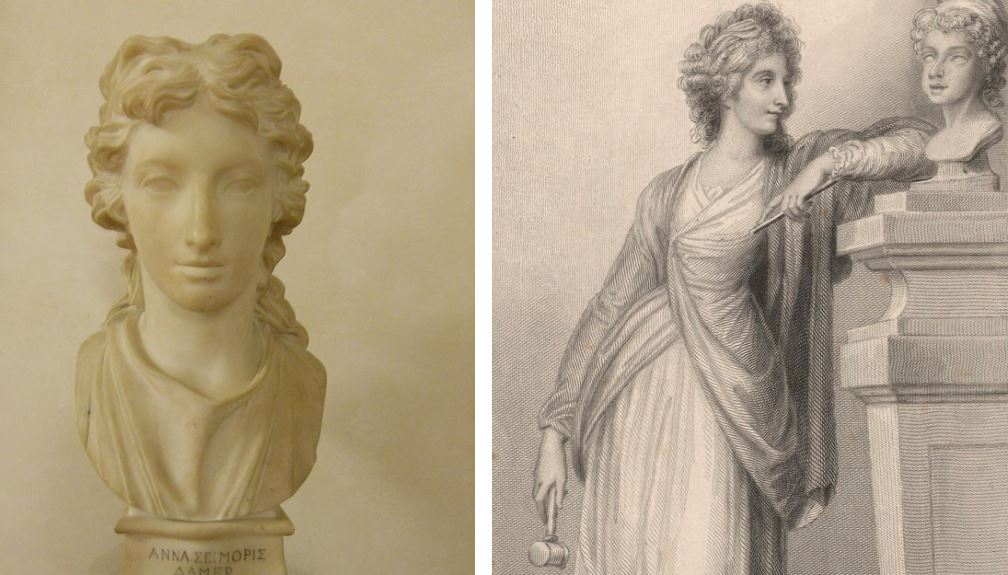

6. Anne Seymour Damer (née Conway): daring to be a sculptor

Anne (1748 –1828) was born into an aristocratic Whig family. Horace Walpole was her godfather, and Anne spent much of her childhood in his home in Strawberry Hill. David Hume, Sir Joshua Reynolds and Horace Walpole encouraged her interest in sculpture. Being financially independent, Anne began building her career as an artist after the death of her husband in 1776. She worked in terracotta, bronze and marble. Being a female sculptor was almost unprecedented; Anne had to face prejudice and ridicule.

Training: she was trained in modelling by Giuseppe Ceracchi, sculptor; in marble carving by John Bacon, sculptor, and in anatomy by William Cumberland Cruikshank, physician.

- She exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1784 to 1818

- Her artistic subjects included Lord Nelson, Sir Joseph Banks, Charles James Fox, George III, Princess Caroline of Wales, and Lady Melbourne, and Sarah Siddons

- Allegedly, she gave private sculpture lessons to Princess Caroline.

- She produced the keystones sculptures of Isis and Thames for the central arch on the bridge at Henley-on-Thames.

by William Greatbach, after Richard Cosway stipple engraving, published 1857

7. Caroline Watson: an independent female engraver

The daughter (1761? – 1814) of an Irish migrant became the first British female professional engraver. She was particularly known for reproductions of miniatures executed in the stipple method.

Training: by her father, the engraver James Watson.

- She produced more than 100 works, and made portraits of i.a. the Princesses Sophia and Mary, Prince William of Gloucester, and Catherine II of Russia

- She was appointed engraver to the Queen, and her patrons included the Marquess of Bute’s family, who commissioned her to engrave several of the Marquess’ pictures

- Caroline was considered as one of the most skillful engravers of her time

- She was the only female independent engraver in Britain in the 18th century

8. Maria Cosway (née Hadfield): the Goddess of Pall-Mall

The Anglo-Italian Maria (1760 –1838), daughter of a British innkeeper at Livorno, was multi-talented: she composed, played music and was a society hostess (her nickname was “The Goddess of Pall-Mall”). She was married to the famed-famous painter Richard Cosway. Together, they were Britain’s first celebrity art-couple. Despite of this, Richard refused to permit Maria to work as an artist professionally.

Training: she studied art under Violante Cerroti, Johann Zoffany, Anton Raphael Mengs, Henry Fuseli, and Joseph Wright of Derby.

- Aged only 18, she was elected to the Florentine Academy. From 1773 to 1778, she copied Old Masters at the Uffizi Gallery

- Angelika Kauffmann helped Maria to participate in academy exhibitions. The Royal Academy of Art displayed more than 40 of her paintings from 1781 to 1801

- From 1801 and 1803, she copied the paintings of the Old Masters at the Louvre (which had been stolen by French armies during the recent Napoleonic War) for publication as etchings in England

- Maria cultivated international contacts in the art world; she had customers from all over the Continent

- Later in life, she settled in Lodi/Italy, and educated elite young Italian women in the liberal arts, music, and fine arts

9. Mary Linwood: making a fortune from embroidery

The daughter (1755–1845) of a wine merchant made the art of crewel embroidery her own. She was the most celebrated needlewoman of her time.

Training: by Matthew and Hannah Linwood, her parents.

- She embroidered her first picture aged 13

- At the age of 20, she had established herself as a needlework artist. She produced a collection of more than 100 textile pictures, mainly copies of old masters, but she also created her own designs

- She held her first London exhibition in 1787. Her exhibition moved to Leicester Square in 1809. It became a must-see attraction and attracted 40,000 visitors per year

- Mary was the first women to run a gallery in London

- In 1790, she received a medal from the Society of Arts

- For 50 years, she led a boarding school where the polite art of embroidery was taught

- Mary’s work attracted the attention of royals in Britain and on the Continent. Catherine the Great offered £40,000 for her complete collection; the Tsar offered £3,000 for one picture. However, Mary generally refused to sell her work. She made her wealth from her exhibitions. Upon her death, her estate was worth £45,000 (£5,199,822 in today’s money)

Ellen Wallace Sharples: family business and the New World

Born into a Quaker family with French roots, Ellen (1769 –1849) specialised in portraits in pastel and in watercolour miniatures on ivory.

Training: by James Sharples, a drawing teacher and pastelist. She later married him. She taught herself how to make miniature watercolour copies on ivory.

- Ellen and James emigrated to America twice to cater for the growing demand for portraiture in the New World. They embarked on a painting tour of New England to pick up lucrative commissions

- Around 1797, Ellen began to draw portraits professionally in order to supplement the family’s income. She copied her husband’s original portraits on commission

- Having returned from America to Britain in 1801, Ellen exhibited her miniatures at the Royal Academy of Arts

- After James’s death in 1811, Ellen and her children settled permanently in Clifton, nr. Bristol, where she established a portrait practice

- Ellen’s subjects in America and Britain included Joseph Priestley, Martha and George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Sir Joseph Banks, and the Marquis de Lafayette.

- She encouraged the career as a painter of her daughter Rolinda, who was elected an honorary member of the Society of British Artists in 1827

- In 1844, she initiated the founding of the Bristol Fine Arts Academy by securing funding

Related articles

Sources

Paris Spies-Gans: “Exhibiting Women: The Art of Professionalism in London and Paris, 1760–1830“, Jul 5, 2022 at https://artherstory.net/exhibiting-women-the-art-of-professionalism-in-london-and-paris-1760-1830/

Amanda Vickery: “Hidden from history: the Royal Academy’s female founders” , 3 June 2016 at https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/ra-magazine-summer-2016-hidden-from-history

Dr Richard Stemp: Mary Moser, 25th Apr 2021 at https://drrichardstemp.com/2021/04/25/126-mary-moser/

Erika Gaffney: Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy; Oct 30, 2019 at: https://artherstory.net/angelica-kauffman-and-mary-moser/

Matthew Hargraves: Maria Cosway Was a Part of England’s First Celebrity Art Couple: June 11, 2020; Yale Center for British Art: https://britishart.yale.edu/maria-cosway-was-part-englands-first-celebrity-art-couple

Heidi A. Strobel: Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act; Apr 19, 2022 at https://artherstory.net/mary-linwoods-balancing-act/

Sotheby’s: Maria Spilsbury, A Sunday-School, at: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2023/old-master-19th-century-paintings-day-auction-part-ii/a-sunday-school

Beetham, Isabella, Mrs (SCC Newsletter September 2011) at: Profiles of the past: http://www.profilesofthepast.org.uk/scc/beetham-isabella-mrs-scc-newsletter-september-2011

Olivia Bladen: Anne Seymour Damer: the ‘Sappho’ of sculpture, 07 Feb 2020, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/anne-seymour-damer-the-sappho-of-sculpture

Natasha Moura: Who was Anne Seymour-Damer? Dec 11, 2029 at https://womennart.com/2019/12/11/who-was-anne-seymour-damer/

The Fitzwilliam Museum: Caroline Watson and Female Printmaking at: https://enfilade18thc.com/2014/08/18/exhibiti on-caroline-watson-and-female-printmaking/

Sara Gray: The Dictionary of British Women Artists, Lutterworth Press, 2009

Jonathan5485: The Sharples Family, at “my daily art display”, March 3, 2012, https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/2012/03/03/the-sharples-family/

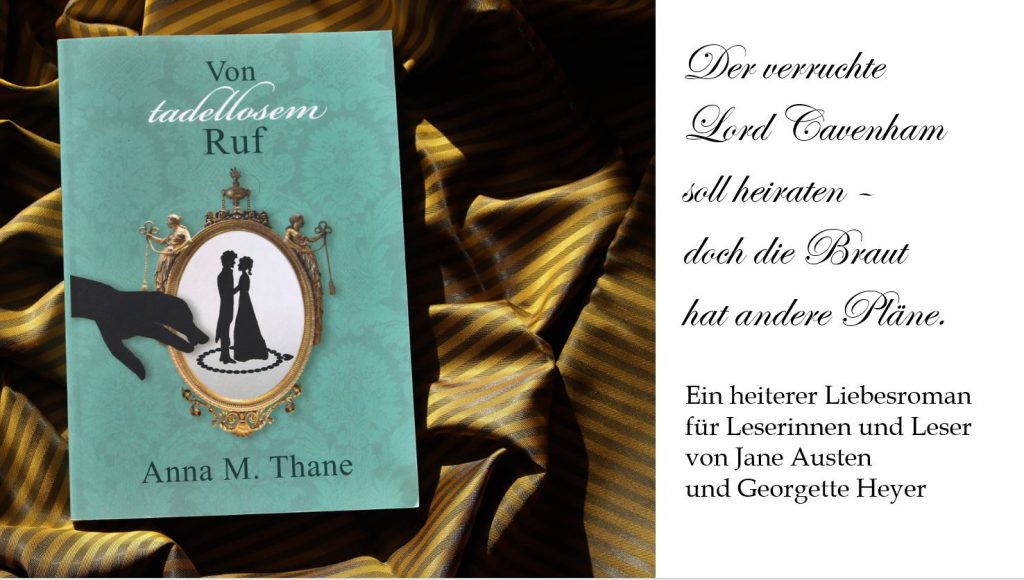

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)