Flying, electricity and computers are part of our everyday lives. When their basic principles were explored during the first half of the 18th century, nobody cared about their practical use. The idea that practical use could be made of a balloon ascent, electricity or the binary code was absurd. Science was mainly aimed at understanding the creation and God. Thus, science was practiced in the “ivory towers” of the elite, written down in Latin and kept in libraries of the chosen few.

However, with a series of breakthroughs in astronomy, chemistry and the study of electricity during the Romantic Age, science became popular. It began to spread into the world, as public lectures and subject in schools. People began to ask how scientific progress and inventions could make life better and easier. Inventive persons set out to develop and pursue new ideas. Soon, new machines were introduced to nearly every industry. Some of them were the origin of the world we know today.

In the new series “The origin of Now” Regency Explorer is going to explore the developments, inventions, and concepts of the Romantic Age that laid the foundations of our modern world. I will explore not only scientific and industrial developments, but also innovations in sports, military, the world of finance etc. Find the first set of examples here.

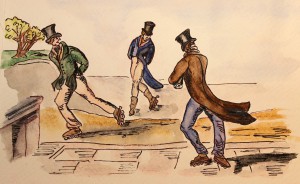

Sports Equipment: Roller Skates

The first metal-wheeled boots literally crashed into society in London at Mrs. Cornelys’s masquerade at Carlisle House in 1760. John Joseph Merlin, the celebrated instrument maker and founder of the then famous ‘Merlin’s Mechanical Museum’, wanted to make a remarkable entrance to the party by wearing a pair of his newly invented skates. Unfortunately, he could control neither speed nor direction. He crashed into a large mirror, damaging the trust in the usefulness of roller skates for several decades.

The first metal-wheeled boots literally crashed into society in London at Mrs. Cornelys’s masquerade at Carlisle House in 1760. John Joseph Merlin, the celebrated instrument maker and founder of the then famous ‘Merlin’s Mechanical Museum’, wanted to make a remarkable entrance to the party by wearing a pair of his newly invented skates. Unfortunately, he could control neither speed nor direction. He crashed into a large mirror, damaging the trust in the usefulness of roller skates for several decades.

How did it work?

Merlin’s roller skates featured a single row of metal rollers fixed to a wood sole attached to a boot. The skaters were difficult to steer and to stop: The break hadn’t been invented yet, and though the rollers were arranged in the style we call ‘inline’ today, it was not possible to follow a curved path or to drive a turn.

From the 18th century to now

It took some time until roller skates became accepted by society. In Prussia, they were part of acrobatics and shows, featuring e.g. in a ballet in 1818. This triggered off their success and made “rinking”, i.e. roller skating, acceptable as a form of recreation.

In 1819, Monsieur Petibledin was the first person to receive a patent on his two- or four-wheeled roller skates. Robert John Tyers of London followed suit in 1823 with a patent for a version with five wheels in a single row on the bottom of a shoe or boot. The skates were still unable to follow a curved path. Despite difficulties in navigation, roller skating became popular. In 1857, two public rings for roller skating opened in London.

The modern roller skate that can manoeuvre in a smooth curve and allows turns and skating backwards was invented in 1863.

Writing Tool: The Steel Pen

For centuries, writing had been done with a goose quill. In 1790, Samuel Harrison produced one of the first steel pens for the scientist Joseph Priestley. 32 years later, steel pens were mass-produced in Birmingham, England’s centre for metalwork.

For centuries, writing had been done with a goose quill. In 1790, Samuel Harrison produced one of the first steel pens for the scientist Joseph Priestley. 32 years later, steel pens were mass-produced in Birmingham, England’s centre for metalwork.

How did it work?

A metal nib for a pen was produced in 13 work steps. About 12 workers were involved.

First, a sheet of metal was passed through rollers until it reached the required thickness. The metal strip was then fed through a hand press. By pulling a handle, a punch was driven into the steel and the piece of metal that was to become the nib fell into a metal drawer below. The nib was placed into a succession of presses to be marked and pierced. To remove the grease and dirt from these operations, the nibs were cleaned and softened in a furnace. Then, the nib was shaped, hardened and scoured. The most important process was the slitting. This enables the ink to run down to the point of the pen. The final touches were cleaning and colouring.

From the 18th century to now

Goose quill pens were no match for the steel pen, for they only had a short working life and needed constant adjustment. In the 1820ies, steel pens could be produced cheaply, making the new writing tool available to many who previously could not afford it.

The first steel pens were dip pens. In 1828, the nib of the steel pens was improved so that it could be added to the more convenient fountain pen. The advantage of the fountain pen is that it contains an internal reservoir of liquid ink. While we usually write with fountain pens today, dip pens are still used in illustration and calligraphy.

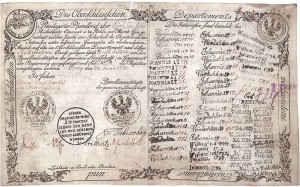

Financial Instrument: Covered Bonds

The first covered bond was created in Prussia in 1769 during the reign of Frederick The Great. It was

The first covered bond was created in Prussia in 1769 during the reign of Frederick The Great. It was

called Pfandbrief.

How did it work?

Pfandbriefe were introduced in order to ease the shortage of credit available to the nobility after the Seven Years War. Associations of noble landowners sold Pfandbriefe for the purpose of refinancing loans to their members. The Pfandbrief was secured by the real estate of the issuing association. The associations were regulated under public law.

From the 18th century to now

The Pfandbrief proved to be a powerful funding instrument. Inspired by the Prussian example, Denmark adopted the system in 1795, when large amount of money were needed to rebuild Copenhagen after the Great Fire had destroyed the town. The Pfandbrief system then spread throughout Europe, and the first mortgage banks were established.

The Pfandbrief is still popular in Germany, and it became the model for covered bonds in other parts of the world. In the long history of this financial instrument, there has never been a default on a Pfandbrief.

Related topics:

- Fashion Meets Scientific Progress: The “Spy Fan”

- The Girl, the Kite and the Eccentric Inventor

- Captain Stanhope’s Invention: A Carriage for ‘The Ton’

- A Traditional Craft: Making Watercolour-Paper

- The Origin of Now: Part 2

- The Origin of Now: Part 3

- The Origin of Now: Part 4

- The Origin of Now: Part 5

Sources

- Shectman, Jonathan: “Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century”; Greenwood, 2003.

- Mobius, Mark: “Bonds: An Introduction to the Core Concepts”; Wiley; 2012.

- The National Roller Skating Museum, 4730 South Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68506, USA

http://www.rollerskatingmuseum.com/homework.html - Kottick, Edward L.: „A History of the Harpsichord“, Band 1; Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Stanyard, Robert: “Tales from the Pen Room”, The Pen Room, Birmingham.

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)