Dear time travelling gentleman on the way to the 18th century, please make sure to take with you one thing: a hat!

In the 18th century, a hat is not only useful in bad weather, and it is more than a fashion accessory. A hat indicates your role in society. Without a hat you are a nobody.

Follow me to a brief introduction to the history of 18th century hats. We make sure you pick the correct one for each period, and we also find out about hat etiquette.

The tricorn that wasn’t a tricorn

For most part of the 18th century, things are easy: The tricorn was the hat of choice for all – rich or poor alike, gentleman or soldier, craftsman or highwayman. Some wealthy women wore it as a part of their riding or hunting attire. There were no set rules how it should be worn: The pointed corner could either be in the middle or at the side.

There is just one thing: Don’t call the hat a tricorn. People wouldn’t know what you mean. The correct name is cocked hat. The name tricorn was only used from the time the hat with three corners had long fallen out of fashion. The Merriam Webster dictionary states the word tricorn was first used as name for the hat in 1823.

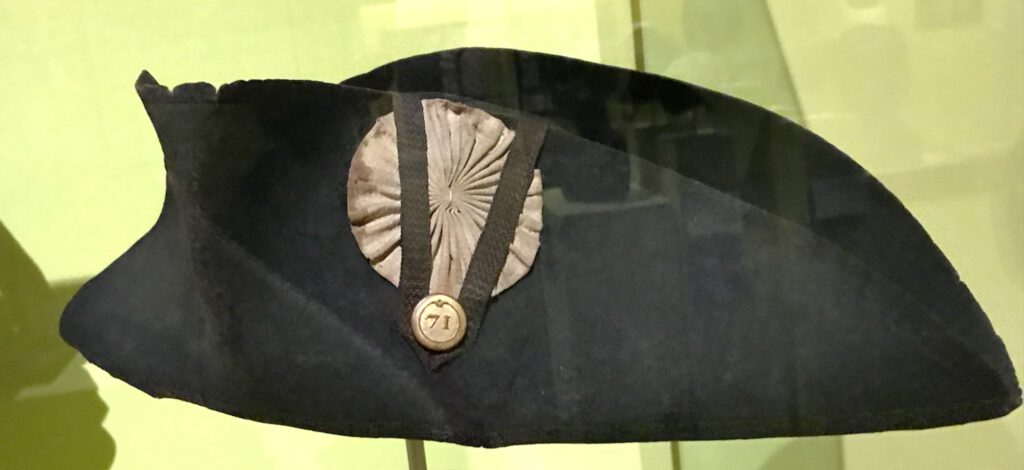

The tricorn fell slowly out of fashion from the 1780ies: The third corner dwindled into a large fold. Thus, a new hat was created: the bicorn.

Modern hats for a modern army

The bicorn (which wasn’t called a bicorn, but a cocked hat) is considered The Iconic Hat of Napoleon. Jacques-Louis David painted one of the most famous portraits, Napoleon at the Saint-Bernard Pass, with the General wearing this special headwear. The painting commemorated Napoleon’s victory over Austria at the Battle of Marengo. It was finished in 1805.

By then, the new version of the cocked hat had become the symbol of a modern, efficient and successful army. It had been created in France, but even the British Royal Navy adopted the hat, wanting to underline their modernity (the British army still preferred the tricorn hat).

The bicorn was a hat for military men. It could be worn in two ways: The corners pointing to the front and to the back, or the corners pointing to the sides. The first version was called en colonne: soldiers chose it when marching with a musket over the shoulder (so that the hat would not be knocked down by the musket). The second version was called en bataille: You look more imposing with the hat sitting on your head with the corners pointing right and left, so it was worn this way when it came to fighting.

The higher the rank of the military man was, the higher and more adorned became the cocked hat. Unless, of course, you are Napoleon. The basic iconic model is yours.

Another hat for the modern soldier was the shako. This tall hat was created in France at the turn of the 19th century. It became fashionable for civilian women who adopted it for their riding attire.

The top hat made civilians feel smart

Civilian men found a replacement for the cocked hat in the top hat. The top hat came into fashion in France from about the 1790ies. It is believed that from around 1793, George Dunnage, a master hatter from Middlesex, introduced the silk top hat to Britain.

One of the most famous portraits of a man wearing an early version of the top hat is again by Jacques-Louis David. In 1795, he painted Monsieur Seriziat, showing his brother-in-law wearing a top hat.

By 1810, the top hat was the headwear of choice for all fashionable men. It was soon adopted by men of all ranks. The top hat made men feeling taller, smarter, and more important. It became a symbol of power, and thus the crown became taller and taller …

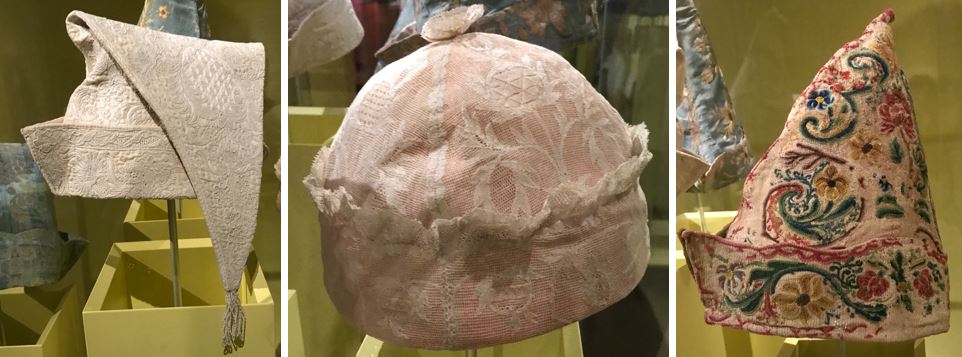

Hats for private life

Wearing a night cap with a splendid nightgown was de rigeur. When a gentleman received visitors informally, he would often wear a house cap. In this case the wig was removed. For caps, a high crown was fashionable in the first half of the 18th century, round caps were preferred in the 2. half.

Hat etiquette – inside, outside and all the things in between

Hats were a must-have: They were worn for business, pleasure and formal occasions. Even in privacy men wore caps. For an 18th century man, hat wearing was an obligation, whatever your station in life might be. If you were rich, you had hats for all occasions: e.g. pearl grey top hats for daytime, black top hats for the evening or for formal occasions.

As a basic rule, a hat was generally worn outside the house. Inside the house, it was taken off. The hall of a house was the place to hand the hat to a servant. However, when making a brief visit, such as a “call of ceremony”, you would remove your hat, but retained it in the hand.

In a pub, the tap-room was considered ‘outside’: hats were kept on. A restaurant and a private club, however, were considered ‘inside’: you would remove the hat. And of course: no hat in a ballroom!

When you met a person outside, you removed your hat for greeting them. However, these rules changed: The deep bowing for men, i.a. bending the body over an outstretched leg, fell out of fashion. It was replaced by a slight inclination of the upper body or even a nod. Tipping the hat instead of taking it off with a huge flourish became common practice unless you met very high-ranking persons.

Related articles

Sources

- Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Prinzregentenstraße 3, 80538 München / Germany

- Musée de l’Empéri, Mnt du Puech, 13300 Salon-de-Provence, France

- Musée de Génie, 106 Rue Eblé, 49000 Angers, France

- Clair Hughes: Hats on, hats off, Cultural Studies Review, volume 22 number 1 March 2016

- Lou Carver: Top This … The story of Top Hats, at: http://www.victoriana.com/Mens-Clothing/tophats.htm

- History of hat making, at: https://www.discoverbritainmag.com/hat-making-history/

- Walter Nelson; Historical Hatiquette (Hat Etiquette); at: Walter’s Random Musings (http://www.walternelson.com/dr/hatiquette)

- Jean Charles Foyer (HatHistorian): https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCr8dSdG9PiPRE19lUMwFyCA/videos

- Penelope Jane Corfield: From Hat Honour to the Handshake: Changing Styles of Communication in the Eighteenth Century; Royal Holloway, University of London: January 2017

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)