In the early 19th century there was hardly a more experienced kingmaker than Napoleon Bonaparte: He had crowed himself as Emperor of France in 1804, became King of Italy in 1805, and made his relatives Kings of the Kingdom of Holland (1806), the Kingdom of Naples (1806 and 1808), the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807) and of Spain (1808). He also made his ally, Maximilian IV Joseph, prince-elector of Bavaria, a King in 1806. The coronation of the King of Bavaria was planned to be a splendid affair, and everyone invested large amounts of money, time and craftsmanship, but alas….

Becoming King

Maximilian wasn’t known best for his bold decision-making. Having to decide between being an ally to Austria or to France, he hovered between the two options like a butterfly between two delicious blossoms. In the end, he opted for France – or rather was persuaded to choose France by his primary advisor, Count Montgelas.

Decision-making was sped along by Austria behaving rather dominantly in the autumn of 1805 when it invaded Bavaria and 200 hussars closed in on one of Maximilian’s residences, Nymphenburg Palace.

The new alliance with France started off rather well: Maximilian had always held pro-French sentiments: He was one of the first to send his congratulations on Napoleon’s elevation from First Consul to the rank of emperor in 1804. He also approved of Napoleon’s idea to marry his step-son Eugène de Beauharnais to Maximilian’s daughter, Augusta de Bavière.

All that was still needed to finally receive the royal title “King of Bavaria” from Napoleon’s hands was Maximilian’s decision to put at the French Emperor’s disposal all his military resources, and defying the Austrian military at Iglau in 1805. Thus, Maximilian was proclaimed King of Bavaria in Munich on January 1, 1806 in the graceful presence of Napoleon and Josephine.

Additionally, Eugène and Augusta married 16 days later. The alliance had been successfully forged.

What could possibly go wrong?

Planning a grand coronation ceremony

As the Kingdom of Bavaria was a constitutional Kingdom, a coronation ceremony wasn’t legally necessary once the King had been proclaimed. But it was of course well known even in 1806 that a glamorous coronation would win the hearts of the population. Naturally, organizing such a ceremony takes some time; it was thus decided that the ceremony would be held a little after the proclamation on January 1, 1806 – dates to be defined.

Money was very tight – Maximilian already had to pay the sum of 1 million Gulden to Napoleon upon setting up the alliance. Nevertheless, the newly baked King made plans for a brilliant coronation ceremony. This included the acquisition of such splendid requisites as crown, sword, sceptre and a coronation coach. Napoleon, ever the patron of arts, was happy to recommend his personal architect, Charles Percier (1764 –1838), for designing the royal insignia.

Having Napoleon taking a hand in the coronation ceremony meant that the style of the event and its requisites would absolutely match Napoleon’s aesthetic ideals. Napoleon admired the late classical style.

Compared to the sumptuous richness of the baroque era, the late classical style was associated with restraint and discipline, certitude and moral truth. Besides, Napoleon used art to convey his strength and grandeur: Egyptian motifs hinted to his campaigns, mythical beasts from antiquity, such as the sphinx, griffon and the chimera, referred to the much-admired Roman emperors, and imperial emblems, including the eagle, the bee, and the letter N, laurel wreaths, medals, lyres, and horns of plenty spoke of glory. So, each requisite used during the coronation ceremony of the Bavarian King would also shout out about the greatness of the Kingmaker, Napoleon.

Creating the requisites of royal power

Personal designers and jewelers of Napoleon set to work for the Bavarian King. A couple of years ago, they had created Napoleon’s crown for the coronation as Emperor in 1804 and as King of Italy in 1805. They kept close to these designs for Maximilian’s crown.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais (1764 – 1843), who had been in charge of the execution of the insignia of Napoleon’s coronation ceremony, was one of the best silversmiths of France. He and Jean-Baptiste Leblond were hired to make Maximilian’s crown; Biennais also made most of the silver service for the Bavarian King.

They worked closely with Marie-Étienne Nitot (1750 1809), the official jeweler to Napoleon since 1802. Nitot was renowned for creating jewellery symbolizing the power that Napoleon wished to convey. He was in charge of the royal insignia of the Bavarian King.

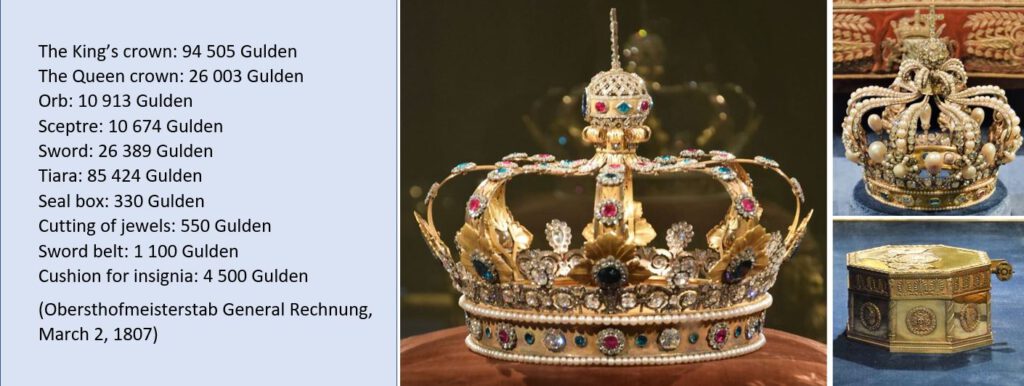

The cost of the crown

Maximilian spent 260.388 Gulden on the crown insignia – about £1,512,069 in today’s money.

From Biennais’ renowned Paris’ workshop crown and insignia were delivered to Munich in March 1807. Yet, there was no scheduled date for the coronation ceremony. Political events precluded it. While one hoped for things to work out fine, there was still time to build a coronation coach.

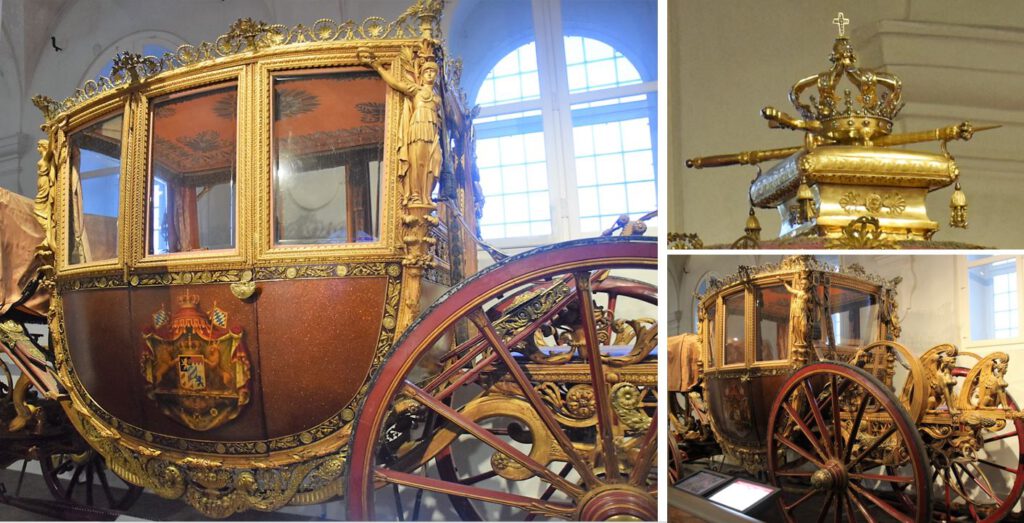

The splendour of the Coronation Coach

The coronation coach was designed by Johann Christian Ginzrot, the royal Bavarian coach building inspector, in the late classical style, modeled on the coronation coach of Napoleon.

Georg Lankensperger, coach builder to the Munich court, built it using the most advanced technology of the day. The wonder of style and technology was finished in 1813.

Alas, the carriage was never used for a coronation ceremony, only to transport the crown insignia to important political events.

How did it end?

For several years, Maximilian had been the most important of the princes belonging to the Confederation of the Rhine. However, the alliance with France wasn’t born under a lucky star. The relationship between Napoleon and Maximilian suffered for various reasons, be it that Bavaria’s rewards for providing ever greater numbers of troops decreased, or that Maximilian refused to introduce the Code Napoléon to the Bavarian Kingdom.

Napoleon’s family affairs didn’t help either: When he divorced Josephine and married the Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria, Maximilian was troubled by dark thoughts about a possible Habsburgian retaliation for Bavaria’s opposition during previous years. When Napoleon’s son was born in 1811, any chance was gone for Maximilian’s daughter to become Queen of Italy.

Again, Count Montgelas, primary advisor of the Maximilian, got to work. He advised to end the French-Bavarian alliance. In October, 1813 Maximilian agreed to join the allies against Napoleon.

Thus, for Maximilian I Joseph, the coronation ceremony never happened.

Related articles

Sources

- Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Zeuggasse 7, 86150 Augsburg, Germany

- Schloss Nymphenburg Marstallmuseum, 80638 München, Germany

- Residenzmuseum, Residenzstraße 1, 80333 München, Germany

- Junkelmann, Marcus: Napoleon und Bayern, Regensburg 1985.

- Wichert, Simone: Wie Bayern ein Königreich wurde, www.br.de

- Sabine Heym, Prachtvolle Kroninsignien für Bayern – aber keine Krönung, in: Bayerns Krone 1806. 200 Jahre Königreich Bayern, hrsg. von Johannes Erichsen und Katharina Heinemann, München 2006, S. 37–49

- Johannes Erichsen und Katharina Heinemann (Hrsg.): Bayerns Krone 1806. 200 Jahre Königreich Bayern, München 2006

- Christian Quaeitzsch: Krone ja – Krönung nein. Prunkvolle Insignien der bayerischen Monarchie in der Warteschleife; https://schloesserblog.bayern.de

- Maximilian I, napoleon.org/en/history-of-the-two-empires/biographies

- The A to Z of Lacquer: Museum für Lackkunst, Windthorststraße 26, 48143 Münster, Germany

- wikipedia.org

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)