In the Georgian age, the book trade flourished in London. Reading was a popular pastime. Books were often read to friends and family for entertainment. Until the end of the 18th century, newly published books were sold without a binding. A person who bought a book received only the printed paper with temporary sewing, a so-called “board”. He/she would go on to engage a bookbinder to have it bound to match his/her personal library.

In the Georgian age, the book trade flourished in London. Reading was a popular pastime. Books were often read to friends and family for entertainment. Until the end of the 18th century, newly published books were sold without a binding. A person who bought a book received only the printed paper with temporary sewing, a so-called “board”. He/she would go on to engage a bookbinder to have it bound to match his/her personal library.

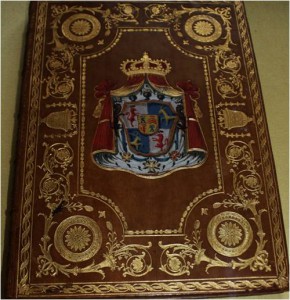

A bookbinding of high quality would find admirers in highest ranks. Wealthy aristocrats and gentry were affluent enough to order specially designed books for their libraries. Their books collections were made to impress, and so the books had to be bound befittingly. Many quality bookbinding workshops were located in Westminster, in the vicinity of the tailors. Thus, a gentleman could conveniently order a new coat and a binding for a new book in one afternoon.

Thanks to patronage of the rich and the development of new techniques, precision in bookbinding improved and the design became more sophisticated. Around 1800, the English bookbinding craft had an excellent reputation for firmness, neatness and gilding. Artist-bookbinding from London was considered the best in Europe.

German Émigrés in London and the Art of Bookbinding

The crème de la crème of the London bookbinders were the German émigrés, which had come to England to escape wars and famine. As a matter of fact, they revived and dominated the English bookbinding in the Regency period. Samuel Christian Kalthoeber was their undisputed king.

Kalthoeber (born 1752 in Prussia, fl. 1775–1817) improved many binding techniques and created his own ornamental designs for stamps. He also revived the art of painting the edges of books, under the gold (click on this link to learn more about this amazing art). Though his competitors were quick to copy his style and techniques, Kalthoeber managed to keep his position as leading artist-bookbinder. He was patronised by King George III, the famous book collector, novelist William Beckford and Catherine the Great. The empress even tried to lure young Kalthoeber to Russia, but he refused her offers. A book bound by Kalthoeber could cost 30 guineas (to compare: an ordinary bookbinder’s weekly wage was 25s). Kalthoeber once bound one of Handel’s oratoria for Zink, a musician at Windsor Castle. Zink appreciated it so much that he asked Kalthoeber to make a case with a secret lock to protect it. This case was so cleverly done that the whole court admired it, and not even the king managed to find the secret lock. In the end, Zink needed a case to protect the case for the book.

Kalthoeber had learned the art of bookbinding from John Baumgarten (d. 1782). Baumgarten probably was the first German bookbinder in the London West End. His workshop was at Duchy Lane (1771-1782). Baumgarten became so famous for his craft that King George had his books made by him, and even Thomas Jefferson in distant America was well aware of his quality binding. John Baumgarten and Samuel Christian Kalthoeber produced excellent work in the classical style, with motives from Greek and Roman antiquity.

How to use London’s Bookbinding Trade in Your Novel

You could easily employ a bibliophile character in your novel. How about a creating a scene in a bookbinding workshop, where the heroine would have to deal with a rough master bookbinder? Or would the villain of your novel steel a valuable book from your heroine and have it rebound to fit his own library, so there is need of a hero to get it back? Whatever your inspiration will be, here are more facts about the trade and its stars:

Famous German bookbinders besides Baumgarten and Kalthoeber in London were Charles Hering, John Henry Bohn, Henry Walther and L. Staggemeier:

- Charles Hering (d. 1809), from Göttingen/Germany, was called “the artistic successor to Roger Payne, the doyen of English bookbinders”. He worked for Lord Spencer and the statesman Thomas Grenville. The wealthy and famous West End clientele such as Lord Byron frequented his shop at 34 St. Martin’s Street.

- Henry Walther (fl. c.1775–1815) had worked with Baumgarten. When Baumgarten died, Walther set up his own bindery at Castle Court, The Strand. He produced high-quality bindings and belonged to the leading bookbinders of his time.

- John Henry Bohn (1757-1843), born at Weinheim on the Rhine, learned the trade in Muenster, Germany. He moved to London in 1790 and set up his workshop in Henrietta Street. He developed a special way of colouring calf-leather.

- L. Staggemeier’s workshop, that he ran with his partner Welcher, was located in Villiers Street. He employed up to 10 men and was famous for his blue morocco binding.

Famous British bookbinders were Roger Payne, John Mackinlay, and Charles Lewis:

- Roger Payne (ca. 1739 – 1797) was the leading bookbinder of the 18th century. His bindings combined elegance and durability; and he chose the ornaments of the cover – circlets, crescents, stars, acorns, running vines, and leaves – with excellent taste. He influenced many German émigré bookbinders in London. His main patrons were the Earl Spencer and the Duke of Devonshire, both noted book collectors and bibliophiles. Unfortunately, Payne was too fond of his drink and tended to quarrel. He didn’t care to comb his hair or to dress properly. He later worked for the famed-famous John Mackinlay (see below).

- John Mackinlay (ca 1745- 1821) a bookbinder from Scotland, was nicknamed ‘Black Jock”. He had such a bad reputation that anecdotes about him were not fit for polite society. Contemporaries described him as “short, thick-set, very shrewd, (and …) a dirty old brute”. He also was unjust, ill-tempered and even abused clients coming to his workshop in Bow Street. John

- Mackinlay was said to be a shockingly bad craftsman, but he managed to employ to best bookbinders.

Charles Lewis (1786–1836), son of a political refugee from Hanover, was apprenticed to bookbinder Henry Walther (see above). In later years, he developed his own style based on the work of Roger Payne. He worked for famous bibliophiles such as the Duke of Sussex, the Duke of Devonshire and Lord Spencer.

Inside a Bookbinder’s Workshop

- A workshop was organized like a factory: Though an apprentice would learn all steps of bookbinding, he later specialized on one aspect of the craft. The finest work was reserved for the master or the most skilled worker. The master’s tasks also included dealing with clients and purchasing materials. A bookbinder could finish 25-30 books per day.

- Women employed in bookbinding workshops were responsible for sewing, folding and piercing. Wages for women workers were much lower than for male workers.

- Work conditions in the bookbinding trade were rougher than in other skilled trades: Working hours for bookbinders were from 6 a.m. – 6 p.m., 6 days a week in 1805. But as there was a lot of work to be done, a working day would often last until 9 p.m. or even 11.p.m. Regular pauses did not exist. The fine bindings were done by candlelight, which must have been a strain on the eyes. Charcoal-heated finishing stoves made the workshops hot and stuffy. Wages weren’t great either: bookbinders were paid were about 3s a week less than skilled workers in other trades.

In the early 19th century, publishers began to take control of the whole book-making process and they began to sell books readily bound.

The bookbinding trade is unthinkable without book printers. Go ahead and have a look at the exhibition about historical printing by Matthias Adler at the Museum of Creativity.

Care for more posts of the Writer’s Travel Guide-Series? Click here.

Sources

Timperley, Charles Henry: A Dictionary of Printers and Printing: With the Progress of Literature, Ancient and Modern; Bibliographical Illustration, etc. etc.; H. Johnson, 1839.

Pearce, Brian Louis: Henry George Bohn (1796-1884): “The Bookseller”; in: RSA Journal, Vol. 140, No. 5434 (Nov. 1992), pp. 788-790.

Prideaux, S.T.: Bookbinders and their craft; Charles Cribener’s Sons, 1903.

Chidley, John: Discovering Book Collecting; Shire Publications, 1982.

Goldstein Marks, Judith: Bookbinding practices of the Hering family, 1794-1844; University of Chicago, 1969.

http://www.aboutbookbinding.com/Books/Book-Binding-108.html

http://www.davidbrassrarebooks.com/wp-content/plugins/wp-shopping-cart/single_book.php/?sbook=2447

http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/untoldlives/2012/12/john-mackinlay-a-dirty-old-brute.html

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=22177

http://www.lib.msu.edu/exhibits/bindings/pages/early19century.jsp

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lewis,_Charles_%281786-1836%29_%28DNB00%29

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Payne,_Roger_%28DNB00%29