Going to the theatre was one of the most popular evening pastimes of the Regency period. It offered more than entertainment, laughter and drama: At the theatre, men and women could meet publicly in society, and classes would mix. Seeing and being seen was also part of the entertainment.

Going to the theatre was one of the most popular evening pastimes of the Regency period. It offered more than entertainment, laughter and drama: At the theatre, men and women could meet publicly in society, and classes would mix. Seeing and being seen was also part of the entertainment.

Though the theatre was popular, it was considered morally reprehensible by the conservative or pious. In Oxford, theatre groups were even banned from performing because of their allegedly negative influence on students.

A theatre is a great location for one or more scenes in a Regency Novel. Use it to introduce a new, villainous character or move the storyline on by getting your main characters into trouble. I have compiled an information kit with 10 important aspects for you to create an authentic scene at a theatre.

Information Kit: 10 Facts about the Theatre

1. A hotbed of sin and sedition

Educational guides warned genteel young ladies of the theatre and advised them to take great care in choosing a play: A lady should never go to a play that could offend her delicacy. A play should always be chaste and instructive.

“‘When going to the Theatre”, advises Lord Chesterfield, author of ‘Principles of Politeness’, “then, let it be to a tragedy, whose exalted sentiments will ennoble your heart.”

Besides picking the appropriate performances, being seen at the right ones was important, too. A genteel lady attending a bawdy comedy would appear bold or unsophisticated.

Besides the priggishly indignant, the authorities regarded the stage with suspicion. Plays were regarded as a vehicle for seditious ideas and blasphemy. Whoever wanted to perform a play for money needed a licence from the Lord Chamberlain (in London) or a magistrate (outside of London). Even more, all scripts had to be approved prior to the performance. Anti-religious or politically dangerous plays were strictly censored.

2. What’s on tonight?

So how would a genteel young lady find information about what was on at the theatres, to pick a decent tragedy?

Theatres provided a different play on each of the six performance nights of a week. Playbills covering the theatre programme of the whole season were yet unknown. The evening ’s play was announced on the previous evening’s playbill and advertised in the daily newspapers on the day of the performance.

From the end of the 18th century it was known up to a week ahead what was on, although still no further in advance.

3. Who is who in the auditorium?

Though all classes visited the theatre, it didn’t mean they rubbed shoulders by sitting next to each other.

The boxes were the most exclusive seats and occupied by wealthy patrons and members of the high society. A seat in a box costed 3 shillings. The wealthy patron and the local magistrate each had their personal box at the very right and left of the stage. Being seated close to the actors was meant as a sign of respect; it also allowed the actors to integrate these high-ranking members of society into the play.

The pit (2 shillings per seat) was the home of the intelligentsia, professionals and critics. The lower classes – tradesmen and craftsmen, hairdressers, apprentices, clerks and labourers – spent 1 shilling for sitting at the crowded gallery.

4. Misery, Crime and Ruin

As a location, the theatre was considered potentially dangerous:

- With health and safety rules still non-existent, the auditorium could be packed dangerously full. Accidents were rare, but it did happen that people were injured or even crushed to death once the doors were opened.

- The crowed rooms offered a perfect hunting ground for pick-pockets.

- Prostitutes on the look-out for new customers mingled in the notorious pit and found easy prey in young, impressionable men.

Small wonder that the conservative or pious associated the theatre with vulgarity and brashness. Again, genteel young ladies should be especially cautious: The private boxes, and especially the small rooms adjoining them, encouraged the improper, warned ‘The Female Instructor’ in 1811: Rakes would take an innocent young lady to the theatre, “to those plays which they knew had a natural tendency to soften and unguard the heart”. The next step would be to seduce the victim and “to abandon her to misery and ruin”.

5. About time

In the early 18th century, a performance used to start in the afternoon as going home after dark was difficult in the dim lighting, and dangerous because of footpads.

With improved security and lighting conditions, the start times of plays grew steadily later. By 1817, the shows at the two main London theatres began at seven o’clock in the evening. The doors to the auditorium opened about one hour before the curtain would rise.

A performance lasted 4-5 hours, with the main play being nestled between songs, dances, acrobatics, clowning or pantomimes. Thus, theatregoers wouldn’t be home before midnight.

6. Reserving a seat – 18th-century style

Booking a ticket wasn’t yet possible. To reserve a seat, there were two options:

- Permanently hiring a box. This could easily cost several hundred shillings a year, and was only for the very wealthy.

- Sending a servant to the theatre when to doors first opened. The servant would sit in the seats needed for the night and thus reserve them. When his masters finally arrived, the servant withdrew. If the servant was lucky, his master arrived late, or rather, in time for the play which usually was number 3 or 4 of the program. Thus, the servant might enjoy a considerable part of the performance.

7. See and be seen

In the boxes of genteel families, the pretty, unmarried daughter sat in the middle of the front-row. This was, of course, to bring her to the attention of eligible bachelors and to show off her taste in morally irreproachable tragedies as well as her sophistication.

The gentlemen would stand or sit in the back of the box. This was not meant as extra security, so that they could prevent strangers from entering the box. It rather allowed the gentlemen to ogle the women in the pit unimpeded and unnoticed by their own female company.

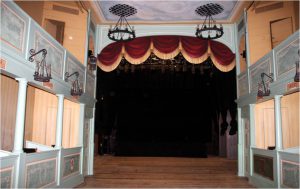

There was plenty to see for the voyeurs: Entrances to the pit was via two pit passages left and right from the stage. Women had to lift their skirts to climb the steps, thus offering the gentlemen in the boxes a good view of their ankles.

8. Rowdies and riots

The ‘kicking board’, or the wooden balustrade at the gallery, used by the audience to express displeasure by kicking at it.

The behaviour of the audience could get loud, bawdy and unruly. People arrived and left throughout the duration of the performance, and they chatted among themselves. Alcohol and food were consumed in great quantity during the show. So called ‘fruit women’ moved among the audience, selling refreshments, copies of plays and books of songs.

Theatregoers reacted to the play by weeping, cheering and hissing. If not pleased with the performance, they threw things at the stage or kicked the wooden balustrade of the gallery.

Riots were not uncommon. The Drury Lane theatre in London was destroyed six times in the 18th century. Riots could break out spontaneously under the influence of alcohol. They could also be planned, e.g. to protest against a price rise for the theatre or an immoral behaviour of a female member of the theatre group. The later happened to the popular actresses Mrs H. Johnston of Covent Garden Theatre. When she returned to the stage in 1807, after two years of absence, she was greeted by a yell of fury. Mrs Johnson was considered guilty of infidelity to her husband, and had failed to display the virtues of discretion, decency and modesty expected of women at this time. Even the famous Sarah Siddons was hissed at when the public believed that success had made her arrogant.

In the case of a planned riot, the female part of the audience was usually led out of the theatre before the action began.

9. The constable steps in!

There were limits to lively or bawdy behaviour. Throughout much of the eighteenth century, theatres employed constables to prevent rowdiness. Two constables took up position on either side of the stage at the start of a performance. Anyone going too far, e.g. by striking and fighting would be brought before a magistrate, and the right to attend the theatre was taken away. The theatres posted the name of the delinquents on their walls to ensure that they did not gain admittance. To be readmitted, they had to pay a fine and promise to behave properly in future.

10. Wowing the Audience

The audience admired sceneries that would create movement and magical effects such as trees growing out of rocks, burning and collapsing palaces, earthquakes, and erupting volcanoes. Below-stage mechanisms created exciting effects: Counter-weighted platforms hurled an actor onto the stage, and trapdoors allowed sudden appearances and disappearances. Ghosts were accompanied by blue, white or red fire.

Technical innovations in electricity and chemistry helped to illuminate the centre of the stage, allowing actors more freedom of movement. In 1784, the Argand lamp, a powerful oil lamp equivalent to the light of 10 candles, was adopted at Drury Lane Theatre. Experiments with gas lighting began in 1803, and lighting of the stage advanced during the Regency period, until it became ‘as bright as day’.

Sources

All photos were taken at the Georgian Theatre Royal in Richmond, Yorkshire.

The Georgian Theatre Royal in Richmond, Yorkshire, is the most complete theatre of the Georgian Age still performing today. It was built by an excellent actor manager, Samuel Butler, in 1788 and run by his family. Actors who performed here included the famous Edmund Kean.

The Georgian Theatre Royal offers a unique view into the history of the theatre. You can take a backstage tour. Link: http://www.georgiantheatreroyal.co.uk/

- The Theatre of Shelley, by Jacqueline Mulhallen; Open book publishers; 2010.

- The Georgian Theatre Audience: Manners and Mores in the Age of Politeness, 1737-‐1810, by Rebecca Wright, Institute of Historical Research.

- Principles of Politeness, and of Knowing the World: Addressed to Young Ladies, Band 2, by Philip Dormer Stanhope of Chesterfield; 1804.

- The Female Instructor; Or, Young Woman’s Companion: Being a Guide to All the Accomplishments which Adorn the Female Character; Nuttall, Fisher, and Dixon; 1811.

- The Georgian Theatre Royal. A Beautiful, Living Theatre, a Vital Part of our Theatrical History, by The Georgian Theatre Royal Richmond.

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)