- Peculiarities of studying in the Romantic Age

- The party life at Oxford University

- Having fun vs. getting into trouble

Like today, studying at the University of Oxford during the Romantic Age opened young adults the way to brilliant careers. Unlike today, studying wasn’t stressful or planned out for undergraduates.

Peculiarities of studying in the Romantic Age

In the 18th century neither credit points nor specialisation had yet been invented, and there was no set curriculum. Every undergraduate studied the same: grammar, logic, rhetoric and languages such as Greek and Latin. If you were interested in seriously studying math, Cambridge was the place for you until 1802. Only then was mathematics included in the curriculum for undergraduates in Oxford. A chair for mathematics had existed before, of course, but undergraduates weren’t expected to have more than a rudimental knowledge of the subject. Examinations – oral, not written – were superficial. Sons of peers were even exempted by their rank from taking an exam.

The party life at Oxford University

If studying was lax, what did undergraduates do at their college? I got the impression that having fun was a central part of university life.

As soon as a first-year university student arrived at the college, he was initiated to 18th-century-undergraduate-party life. It was common to make freshers drunk each day of their first week at college. This ritual was intended to help the freshers find friends and his social group in one of the clubs.

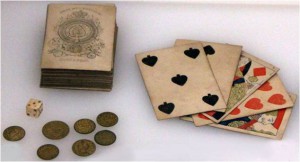

Many different clubs existed at the colleges, but few of them were sophisticated gatherings focussing on reading Greek while drinking water. Most clubs had alcoholic drink, smoke and song on the agenda. Jolly parties often ended in a brawl.

Having fun vs. getting into trouble

While party-life and drinking to excess inside the walls of the colleges were perfectly legal, many other activities weren’t. Proctors controlled the undergraduates’ social life and pastime. Many rules had been designed to guide the steps of the undergraduates, and many activities were explicitly forbidden:

Reality: The University fought a losing battle. The sons of peers were exempted from the ban on riding anyway, and as riding was immensely popular also less privileged undergraduates carried on with the sport regardless of the rules. Stables and horse-hiring establishments were willing to hire their horses to unlawful riders.

Reality: Students considered breaking this rule a kind of sport. They simply hid when a proctor in search of wrongdoers entered an inn or tavern. If this failed, being caught by the proctor was considered part of the fun.

If an undergraduate was in the company of a graduate, a visit to a tavern was totally legal. Thus, some students boldly claimed to be at the inn with a doctor or master, so that the proctors had to retreat.

Rule: No Hunting and owning a gun!

Rule: No Hunting and owning a gun!

University regulations were very clear about this rule and even included clauses for local gunsmiths: They were forbidden to lend or hire guns to undergraduates.

Reason: Too dangerous, expensive and time consuming

Reality: The University management could have spared its breath. Country gentlemen weren’t willing to give up their favourite pastime. They stabled their hounds and horse on the edge of Oxford and rode off to hunt whenever possible. Pigeon shooting was particularly popular with undergraduates. In those days, it was done with real pigeons as targets that were released from a basket.

Rule: No Women at university!

Rule: No Women at university!

Reason: Local ladies who aimed to marry above their rank dangled after undergraduates. The rich and titled students were especially sought after by the daughters of the bourgeois, and also by the fancy ladies of the demi-monde.

Reality: Who cares? Stung by cupid’s arrow, enterprising undergraduates smuggled females – often of ‘low reputation’ – into the college. Most of these ‘visitors’ were discovered after one or two nights. There is however at least one known case when a woman shared a room with an undergraduate for about half a year. She had herself cleverly disguised as a man. Her cover only blew when she became pregnant.

Besides, university management tripped itself up as there actually were women present at every college all the same, and even in the undergraduates’ room: the bedmakers. In those days, undergraduates wouldn’t have dreamt of making their beds or cleaning their rooms themselves. Servants were in charge. Bedmakers could be elderly and unattractive, but also young and pretty. They often became the object of forbidden undergraduate gallantry – and the victims of its consequences.

Reality: All in vain. In those days, visiting a theatre was as popular as going to the cinema is today. It only was a minor problem for the theatre enthusiast that theatre groups were not allowed to perform in Oxford. Theatres flourished, however, in the surrounding villages. Thus, students who enjoyed seeing a play were tempted to a forbidden night out, riding (on the forbidden horse) to a theatre some miles away and creeping back into their room at dawn.

Pushing the boundaries of what was allowed or not must have been very tempting for undergraduates as many of the forbidden activities were typical pastimes of gentlemen.

I mentioned the privileged group of students, the sons of the peers, which was exempted from most rules and prohibitions. They were a class of their own, but they were not the only class of students at the University of Oxford. There were four classes of students, and each of them had its own goals, living conditions, appearance and rules for behaviour. Read more about it here .

Sources

Midgley, Graham: University Life in Eighteenth-Century Oxford; Yale University Press, 1996.

Porter, Roy (Editor): The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 4, Eighteenth-Century Science; Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)