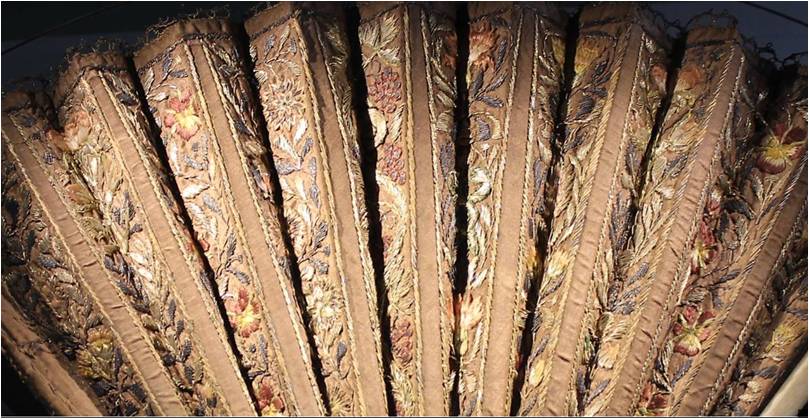

Palmette fan from 1680. The elements of the leaf are made of silk fixed on cardboards and are painted with gold and silver.

This post celebrates a fabulous fashion item: the hand-held fan.

From a ceremonial tool used in churches it developed into a must-have accessory of the high-society. Designs and materials varied with politics, social changes and fashion. Still, the fan always was an object of breathtaking beauty.

Enjoy the photos and the brief overview of the history of the fan in England. You can click on the photos to enlarge them.

Fans in the 17th Century: From Status Symbol to Fashion Accessory

Folding fans become popular in Europe from the late 16th century. France, always the leader of fashion, soon warrants four groups of craftsmen to work together to create high-quality folding fans for nobility. It takes 100 years for the English society to follow.

Elizabeth I. is the first Englishwomen to carry a fan. Though she is today credited with bringing the fan into fashion in England, it is a status symbol for ladies of highest rank from the late 16th to the early 17th century.

It is only with the restoration of 1660 and the end of Cromwell’s radical puritanical reign that fans become a must-have accessory for every lady in high society.

In the first decades of fan fashion, the leaves are made of paper or silk. It is popular to paint them with religious and classical motifs. The leaf is often wedge-shaped, opening to an angle of only 45 degrees, thus providing an ‘oriental’ flair.

From the 1720ies, the so called brisé fan becomes fashionable in Europe. It consists completely of pierced material such as ivory and tortoise shell.

Fans in the 18th Century: A Must-Have for Ladies and Gentlemen alike

The trend to carry a fan spreads rapidly through society, and fan making becomes a lucrative business. In 1709 the first English guild of fan makers is founded. The demand is so high that fans are also imported from the continent, especially France, and China.

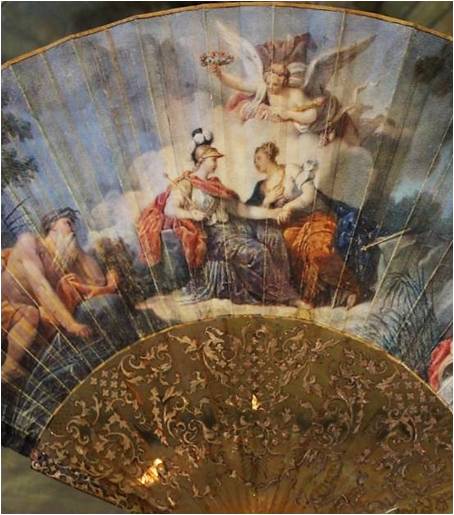

Fans are so popular that they are carried by ladies and dandies alike. Fans for men replace the dress sword as accessory. Throughout most of the century, a luxurious design is a must for fans: The sticks and guards are made of precious material such as ivory, bone, mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell, and they are often highly adorned with jewels, silver and gold work or inlays. The leaf becomes larger, and from about 1750 it reaches the full semicircle.

The fan leaves are decorated with mundane topics such as pastoral scenes, al fresco parties and themes of love-and-courtship.

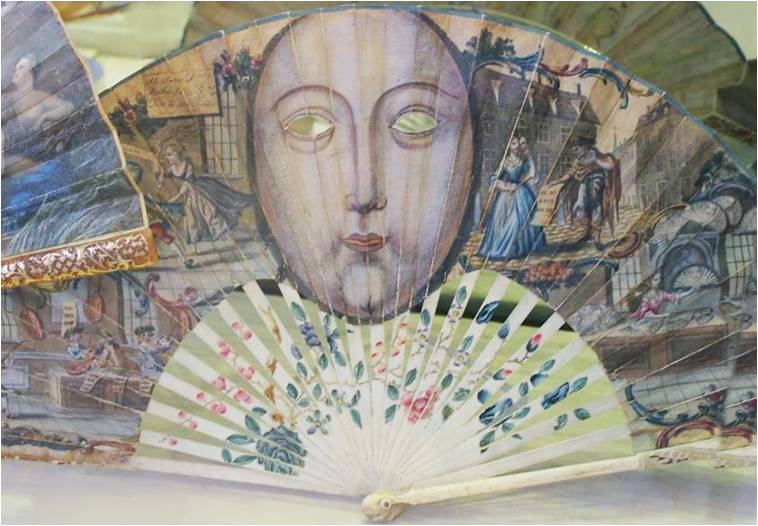

The painting does not form an all-over composition, but consists of a series of small vignettes that might tell a little story.

Fan titled ‘La folie des dames’; it shows a hairdressing scene outside; the hair-stylist uses a ladder to reach the top of the wig; 1750.

Fans imported from China feature either the fashionable chinoserie style depicting a clichéd ancient China, or English motifs interpreted by Chinese artists.

The Fan in the Romantic Age: Revolution in Style and Production

The French revolution changes politics and society for ever. It also changes fashion. Gone are the heavy, colourful brocade fabrics, laces and hoops of the aristocracy. The new dresses for women are made of light, transparent fabric and discreet colour. The silhouette is slim, inspired by the Greek toga. The change in fashion means that women can’t wear their pockets under the skirts any longer. It would ruin the slim silhouette. As a consequence, a new accessory is invented: the reticule, a little bag hanging from the wrist. Fans must now be small enough to fit into the reticule.

The design of the fan should contrast the simple style of the dress. Ornaments made of sequins and gilt shapes glitter in the fan leaves. Such designs were faster and cheaper to produce than elaborate paintings by hand.

Printed fan commemorating King George III.’s escape from assassination. He was attacked by James Hatfield in Drury Lane Theatre on 15 May 1800.

The cockade is a new style for fans: the leaf opens into a complete circle around the pivot.

With the early industrialisation and the beginning of mass production in the late 18th century, the printed fan is introduced to the English market. Production is cheap and prices fall. The middle class happily buys fans commemorating political or royal events. These fans might be used for one ball or event only.

From the 1820ies, brisé fans have their comeback. Their sticks are often shaped à la cathedral (like a church spire or spearheaded), echoing the rise of the neo-gothic style. The sticks are made of horn and bone which is cheaper than ivory and tortoise shell. The decoration is also done in a cost-effective way, often featuring only a few painted flowers.

Horn brisé fan ‘a la cathedral‘ from 1825. The sticks are made of mother of pearl and silver and gold foil.

The invention of machines to fold fans und to cut and pierce the sticks furthers mass production.

Click here to go to the post “The unrivalled beauty of the hand-held fan” and enjoy more fans from the Romantic Age.

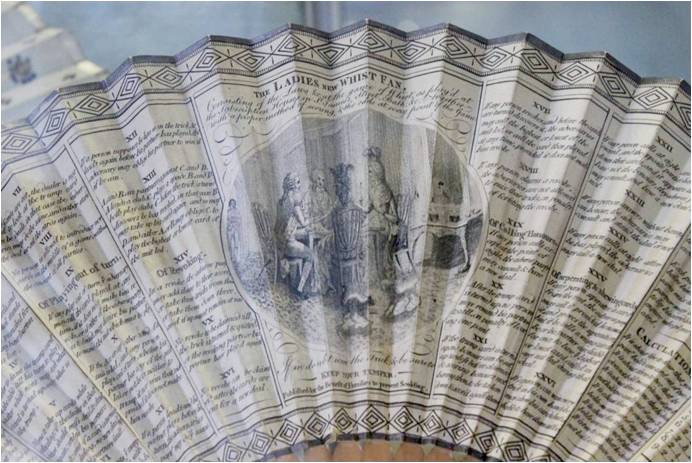

Handy tool for card parties: A printed fan with directions for playing the game of whist; from 1790.

Towards the total commercialisation of fans

The 19th century sees a wide variety of fashion styles for fans:

After the Boer War, fans made of ostrich feathers from South Africa become popular.

The Victorians rediscover their love for the baroque period. Painted fans feature sugary 18th-century motifs.

Pretty Pretender: This fan is not from the baroque era but from 1860. It is painted with a ball scene at the court of Louis XV.

In the 1880ies, fans become very large to match the fashion. Lace is the most popular material for the leaves.

At the same time, the painted fan depicting scenes of the world of the bourgeoisie is popular.

With the arrival of the 20th century and a more modern and democratic society, the function of the fan changes. It survives as a fashion accessory until well into the 20th century but its days of glamour in the hands of the social elite are over. Fans are now an everyday item, being used as an advertising instrument of hotels, shops and theatres. Nevertheless, it is still important to maintain the image of luxury. Artists of repute design high-quality motifs for the fan leaves to underline the classy image of a brand.

Fan advertising the perfume ‘Pompeia’ by L.T. Piver, probably from 1907. It is made of wood and paper. The baroque motifs underline the luxurious image of the perfume.

Related topics

- The Unrivalled Beauty of the Hand-held Fan in the Romantic Age

- Fashion Meets Scientific Progress: The “Spy Fan”

- A Brief History of the Napoleonic Wars told … in 10 Hand-held Fans

Sources

http://www.fanmakers.com/history/a-short-history-of-hand-held-fans/

- Museum of London, 150 London Wall, London EC2Y 5HN, UK

- Victoria & Albert Museum, Cromwell Rd, London SW7 2RL, UK

- Arlington Court, Arlington EX31 4LP, UK

Alexander, Hélène: Fans; Shire Library, 2002.

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)