Find in this travel guide for the 18th century:

Find in this travel guide for the 18th century:

- The Antiquities Trail:

– Herculaneum and Pompeii

– Paestum - Practical Tips for Travellers

– Where to Stay

– Specialities - Danger & Annoyances

- Money & Measurements

The Kingdom of Naples and Sicily became a popular destination for British tourists with the discovery and excavation of ancient ruins in the mid 18th century. The art found at Herculaneum and Pompeii sparked the European Neo-classicism: It was the motifs from these ancient ruins that featured on stylish furnishings in England.

Architects, artists and their rich patrons braved the inconveniences of a long journey to see the celebrated ruins themselves.

Architects, artists and their rich patrons braved the inconveniences of a long journey to see the celebrated ruins themselves.

In this part of ‘Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples’ we discover the famous ancient sites as a travel destination for Grand Tourists of the Romantic Age.

The Antiquities-Trail

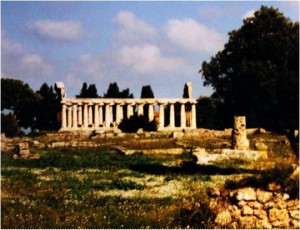

From the late 1730ies, an interest in classical antiquity leads to a methodical excavation of several ancient ruins. Initially, the focus is on Herculaneum and Pompeii. The temples at Paestum are the last to be explored. As Paestum doesn’t look like a typical Roman ruin, scholars doubt the place is worth their full attention. But the completeness of Paestum’s ruins fascinates architects, artists and tourists alike. From the second half of the 18th century, Paestum becomes a much-admired destination for lovers of antiquity.

Herculaneum and Pompeii

The town Herculaneum, located about 8 miles from Napoli, was submerged by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. In 1738 the excavations of Herculaneum begin by order of the King of Naples. It is hard work: The layer of debris covering the side measures up to twenty meters. When excavations start at nearby Pompeii in 1747, works stop at Herculaneum in favour of these more easily accessible ruins.

The town Herculaneum, located about 8 miles from Napoli, was submerged by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. In 1738 the excavations of Herculaneum begin by order of the King of Naples. It is hard work: The layer of debris covering the side measures up to twenty meters. When excavations start at nearby Pompeii in 1747, works stop at Herculaneum in favour of these more easily accessible ruins.

Though excavations have stopped, it is still possible for travellers to visit Herculaneum. Entrance to the ruins is from the town of Portici. 72 ancient steps lead to the subterranean city. Visitors can see several rooms with wall paintings and marble floors worked in mosaic, niches with urns that are still filled with ashes, and the remains of a theatre. ‘The theatre is (… ) open to inspection (…), but the darkness is too deep to be dispelled by the glare of a few torches. Some of the seats for the spectators and the front of the stage are the only objects distinguishable’, writes John Chetwode Eustace in 1802.

The interest in the ruins at Pompeii is immense, but it takes 16 years until travellers are allowed to visit the site. From 1763, they can admire the Temple of Isis, the theatre, the Herculaneum Gate and the Villa of Diomedes. Works continue during the French rule from 1805-1815. The French discover, among others, the forum and the Via Mercurio.

The artefacts found at the sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii are kept in a museum at the Royal Palace at Portici. Travellers might find this unfortunate, but nevertheless, Pompeii possesses a secret power that captivates the visitors’ hearts. They are fascinated by wandering through the same streets, enter the same doors and behold the same walls at the Roman inhabitants did. Yet, is a silent and lost city they discover, without sounds to disturb the loneliness of the place. To quote John Chetwode Eustace again: ‘All around is silence, not the silence of solitude and repose, but of death and devastation, the silence of a great city without one single inhabitant.’

Access to the artefacts kept at the museum is strictly controlled. Though some visitors are allowed to see the treasures, they are forbidden to draw or take notes. As publications about the art treasures don’t exist, the knowledge about Herculaneum is the reserve of an elite.

A Special form of Art Theft

A group of noble French travellers with extraordinary memory and drawing skills bring the art treasures of Herculaneum und Pompeii to the world in 1755: After their visit to the royal palace they make sketches of the antiques they have seen. They publish these drawings in Observations sur les antiquités d’Herculanum avec quelques réflexions sur la peinture & la sculpture des anciens; & une courte description de plusieurs antiquités des environs de Naples. The book becomes an overnight success in Europe (you can read it online here).

Being thus outsmarted, the King of Naples can’t help but lift the strict control over the antiques. Successively, eight volumes about the ancient art treasures are published (have a look at Volume 1 here: Le Antichità di Ercolano Esposte (Antiquities of Herculaneum Exposed)).

Paestum (Pesto)

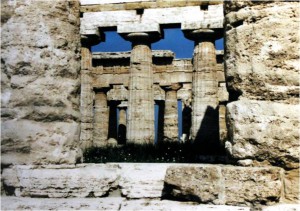

Paestum, about 54 miles south of Napoli, is a dangerous, but tempting destiny. It is located in a malarial swamp, and travellers should be prepared to encounter venomous asp vipers and scorpions. Nevertheless, the main monuments, three Doric temples, are well worth a visit. Scholars believe that the monuments are of Roman origin (today we know they are Greek). They identify them as a basilica and as temples of Neptune and Ceres.

Paestum, about 54 miles south of Napoli, is a dangerous, but tempting destiny. It is located in a malarial swamp, and travellers should be prepared to encounter venomous asp vipers and scorpions. Nevertheless, the main monuments, three Doric temples, are well worth a visit. Scholars believe that the monuments are of Roman origin (today we know they are Greek). They identify them as a basilica and as temples of Neptune and Ceres.

Moreover, Paestum is renowned for its historical rose trade. The famous Paestum rose (biferi rosario Paesti) blooms twice a year, is deeply red and has an unrivalled fragrance. Ancient Paestum had been the main manufacturer of rose perfume. In ancient times, resins made of roses were continuously burned on the altars of the temples and scented the air of the city. A few rose bushes, remnants of those days, flourish neglected here and there at the site.

The trip to Paestum can not be done in one day. The traveller might stay at an inn in Pesto. Some offer a direct view of the ancient site:

The trip to Paestum can not be done in one day. The traveller might stay at an inn in Pesto. Some offer a direct view of the ancient site:

‘The night was bright (…) no sound was heard but the regular murmurs of the neighbouring sea. The temples, silvered over by the light of the moon, rose full before me, and fixed my eyes till sleep closed them. In the morning, the first object that presented itself was still the temples, now blazing in the full beams of the sun’, writes John Chetwode Eustace

Practical Tips for Travellers

Where to Stay

At Naples, some hotels have specialised in the reception of foreign visitors. The Li tre Re, La Croce D’oro and Alle Colombe are popular among British travellers from about 1750. The hotels offer board and lodge for 10 to 15 Carlini a day. They also provide their guests with a coach for 12 Carlini a day. The cooks of the hotels are considered excellent.

At Naples, some hotels have specialised in the reception of foreign visitors. The Li tre Re, La Croce D’oro and Alle Colombe are popular among British travellers from about 1750. The hotels offer board and lodge for 10 to 15 Carlini a day. They also provide their guests with a coach for 12 Carlini a day. The cooks of the hotels are considered excellent.

Later in the 18th centure, the inn Grand Bretagne becomes popular. It is located at the seashore, close to the royal garden. The views of the sea delights the guests.

Besides hotels, furnished lodgings can be rented for longer stays. There are several lodgings at or near the Piazza de Castello. They offer a beautiful view of the sea. Several good inns are nearby that will send well-dressed and hot provisions to the lodgings at any time.

Specialities

Some authors of travel descriptions claim that the Italian wines are too luscious and too racy to suit the English palate. However, the wine Lacryma Christi, produced at the slope of Mount Vesuvius, is considered as rich and delicious. Also the wine from the isle of Ischia is popular with English travellers

Some authors of travel descriptions claim that the Italian wines are too luscious and too racy to suit the English palate. However, the wine Lacryma Christi, produced at the slope of Mount Vesuvius, is considered as rich and delicious. Also the wine from the isle of Ischia is popular with English travellers

With regard to non-alcoholic refreshments, Neapolitans are very partial to iced water. It is brought from the mountains to Naples by boat every morning.

Regarding food, travellers should try the local macaroni. Historically, macaroni were mostly eaten by the privileged aristocracy of Sicily. Additionally, little biscuits called taralli made from flour, olive oil, salt and pepper, are a popular snack.

Dangers & Annoyances

Crime

Naples is a fairly safe city for travellers. Drunkenness is not a common vice, and so quarrels are rare, writes Henry Swinburne in 1786. Visitors also don’t need to worry about riots, burglaries or assassination in the capital. However, travellers should be aware of pickpockets.

Prostitution is far less visible in Naples than in London. The business is completely operated via pimps that contact a potential customer on the street. The prostitute waits in a closed carriage, hidden from view.

The mountainous areas of the countryside have a reputation for violence and murder. Additionally, highway robbery is a common phenomenon on the roads. In the late 1780ies, a traveller might encounter the famed bandit ‘Fra Diavolo’.

Insects and Reptiles

Mosquitoes plague many swampy areas, e.g. the area of the ancient ruins of Paestum. The south of Italy is also the habitat of venomous asp vipers, the poisonous tarantula wolf spider, and scorpions.

Malaria

In swampy areas travellers must be careful to not contract malaria. The cause of the potentially lethal disease seems to be putrefied air and noxious vapours. In the hot months, also called the malarial season, swamps are best to be avoided. Only after the heavy rains in September and October, when the air has been cleaned, it is considered save to go to areas such as Paestum.

Money & Measurements

The currency of the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily is the Neapolitan piastra. Circulating coins are grano, tornese, cavallo, carlino and ducato. The cavalli and tornesi coins are struck in copper, the grana in silver and the ducats in gold.

120 grana are worth one piastra. 1 ducat contains 10 carlini, 1 carlini contains 10 grano and 1 grano contains 12 cavalli. The 1 ducat is worth about 3 shillings 9 pence, and one carlino is about 4 ½ pennies.

The Kingdom of Naples’ has its own measurements:

- A common weight is the rotolo which is about about 0.9 kg.

- Wine is measured by the barrel. One barrel contains 66 caraffi, which is equal to 9 ½ English gallons.

- Distances are indicated in mile (about 1.84 km).

Coming soon: Inside the Palace of Caserta – including gossip about the British social elite frequenting the palace!

Related topics

- Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 1)

- For all posts of the Writer’s Travel Guide-series: Click here.

Sources

- Mazzinghi, Giovanni: Guida alle antichita, e alle curiosita nella citta di Napoli e nelle sue vicinanze, etc. – A Guide to the Antiquities and Curiosities in the City of Naples and Its Environs.); Naples, 1817.

- D’Amore, Manuela: Southern Routes in the Grand Tour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society and the “Discovery” of the Kingdom of Naples. http://revel.unice.fr/symposia/actel/?id=748

- Swinburne, Henry: Travels in the two Sicilies; London, 1783.

- Wright, Edward: Some observations made in travelling: through France, Italy, etc. in the years 1720, 1721 and 1722; London, 1730.

- Northall, John: Travels through Italy, containing new and curious observations on that country, etc; London, 1776.

- Rev Chetwode Eustace, John: A tour through Italy: exhibiting a view of its scenery, its antiquities, and its monuments, particularly as they are objects of classical interest and elucidation : with an account of the present state of its cities and towns : and occasional observations on the recent spoliations of the French, London, 1813

- Black, Jeremy: The British Abroad: The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century; The History Press, 2003.

- https://sites.google.com/site/theauthorityofruins/herculaneum-and-pompeii-in-the-18th-century/pompeii-and-herculaneum-in-the-18th-century

- http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Kingdom_of_Naples.aspx

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)