From August to October, dahlias turn gardens into a sea of vivid colours. The Victorians loved the exuberant plant. But how was the flower perceived in the Regency period? Was it commonly found in the gardens of ordinary people, or was it only a favourite of botanists?

In a Regency novel by Georgette Heyer, we find the following humorous lines:

“(Venetia) directed an aged and obstinate gardener to tie up the dahlias. It seemed improbable that he would do so, for he regarded them as upstarts and intruders, which in his young days had never been heard of, and always became distressingly deaf whenever Venetia mentioned them.”

These lines always make me smile. Yet, how much historical correctness do they contain? Let’s find out.

“Venetia” is set in the year 1818. The heroine belongs to the gentry, and her estate, Undershaw, features a fine garden. The gardener, characterised as ‘aged and obstinate’, might be about 55 years old. Let’s say he was born in 1763. His young days, therefore, were between 1783 and 1798. What was known about the dahlia in Britain at that time? And how likely was it that Venetia’s garden featured dahlias?

The Dahlia Arriving in Britain

Spain was the first European country to receive seeds and tubers of the Central American dahlia in 1789. From there, it was sent to France, Italy, Germany – and was also given to a few British enthusiasts.

Dahlias and the Aristocratic Circle

Some sources claim that as early as 1789, the Marchioness of Bute, temporarily residing in Madrid with her husband, received seeds from the director of the Royal Gardens of Madrid. She promptly dispatched them to England. Other sources give the year as 1798 – but we will not delve into this in detail. All sources agree that the plants grown from these seeds didn’t survive long in the British climate and under inexperienced care.

Elizabeth, Lady Holland, had more luck in 1804. She, too, received dahlia seeds in Madrid and sent them to her home, Holland House. Under the tender care of Serafino Buonaiuti, a factotum who assisted in the library, the plants prospered. Buonaiuti obtained double flowers from two seedlings in 1805. Legend has it that a London florist offered the princely sum of 30 guineas for a single tuber of the Holland House dahlia.

Dahlias as Research Objects for Botanists and Enthusiasts

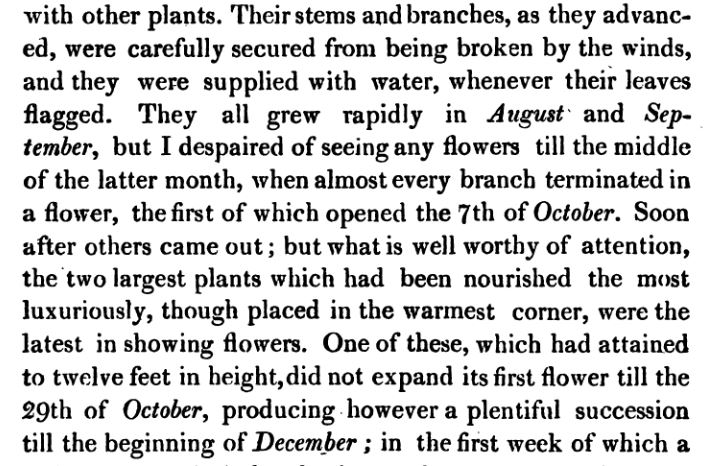

Seeds and tubers of the dahlias thriving in the gardens of Holland House were given to British botanists such as Richard Salisbury, one of the founders of the Royal Horticultural Society. In 1806, he successfully grew dahlias and presented his results to the members of the Royal Horticultural Society in April 1808. Salisbury saw the plant’s potential as a decorative garden flower: being the dark purple variety and planted in the middle of an open grass plot, it attracted far more attention than the venerable chestnuts, magnolias, cembra pines, cedars, and cypresses. Salisbury’s observations were published in the first volume of the Transactions of the Royal Horticultural Society.

While the prize for the first British scientific work on dahlias may go to Salisbury, the one for the first garden dahlia to be grown in Britain goes to John Woodford. This amateur plant enthusiast grew a Dahlia rosea from seeds bought in France in 1802 in his garden in Vauxhall.

Close on his heels was John Fraser, a nurseryman and collector of American plants. He obtained seeds of Dahlia coccinea from Paris in 1802. The plants flowered in his greenhouse in 1803.

John Wedgwood, son of pottery-firm founder Josiah, and co-founder of the Royal Horticultural Society, grew 200 varieties from 1805. He contributed his observations to the first volume of the Transactions of the Royal Horticultural Society.

Conquering the Hearts of Gardeners and Plant Lovers

In 1804, dahlia seeds were brought to Paris and Berlin by Alexander von Humboldt, returning from his expedition to the Americas. Soon, French and German botanists experimented with growing dahlias. The various species began to share genes and hybridise, leading to new colours and forms.

Britons who visited the Continent on the return of peace in 1814 adored the splendour and variety of the dahlias. This kick-started renewed activities in raising new varieties, both of the single-type flower and also of the double flowers. All of them were still forerunners of the present varieties such as pompom and cactus dahlias. Among the successful commercial breeders were Lee and Kennedy’s Hammersmith Nurseries in England. They produced a purple double dahlia called Dahlia purpurea superba in 1816, and many more varieties. The cost of a tuber varied from £2 to £25.

By 1818, catalogues listed about 100 to 150 named varieties, mainly single-flowered dahlias. In 1822, the Hammersmith Nurseries’ collection boasted over 200 varieties. The first exhibition of dahlias was held in Scotland in the same year. 1821 saw the first white double dahlia. It was named ‘Waverley’, after Walter Scott’s successful novel. By 1822, the dahlia was considered the most fashionable flower in the country.

Conclusion

Though botanists and well-connected people of high society had read about the exotic dahlia by the late 1790s, the common gardener, as we find him in Georgette Heyer’s Regency novel, would indeed not have had to deal with them – yet. After being studied by naturalists in the first decade of the 19th century, dahlias ventured into the regular gardens of the gentry from about 1814. Thus, in 1818, they may have been in Venetia’s garden in Yorkshire for a few years. Georgette Heyer’s putting the word “upstarts” in the grumpy gardener’s mouth is – if not kind – historically correct. However, with costs starting from £2 per tuber, the dahlia would still have had to make its way into the gardens of average people.

Related articles

Sources

- Antonio José Cavanilles: “Images and Descriptions of the Plants that Grow Spontaneously in Spain or Are Hosted in Gardens, 1791 and 1795

- R. A. Salisbury: “Observations on the different species of Dahlia, and the best method of cultivating them in Great Britain” in: Transaction of the Horticultural Society, Vol 1, London, 1808

- George W, Johnson and J. Turner: “The Dahlia: its culture, use and history”. In: Gardener’s Monthly Volume, London; 1847

- Richard Dean: “Dean’s History of the Dahlia”, 1913

- The Stanford Dahlia Project: “A Short History of Dahlia Hybridization”, at: https://web.stanford.edu/group/dahlia_genetics/dahlia_history.htm

- The Stanford Dahlia Project: A Timeline of Important Dates in Dahlia Cultivation and Hybridization, at: https://web.stanford.edu/group/dahlia_genetics/dahlia_timeline.htm

- Karen Meadows: “The Dahlia“, 2018, at: https://www.waterfurlonggardens.com/single-post/2018/09/11/the-dahlia

- National Dahlia Society: “History of the Dahlia”, at: https://www.dahlia-nds.co.uk/about-dahlias/history/

- Staffordshire Archives and Heritage: The Dahlia Craze, 10. Dec 2020, at: https://shcvolunteers.wordpress.com/2020/12/10/the-dahlia-craze/

- William Hooker: The Paradisus Londonensis : or Coloured Figures of Plants Cultivated in the Vicinity of the Metropolis”, London 1805

- Historic Dahlia Archives: Texnier’s Le Dahlia (1909), at: https://www.dahliadoctor.com/blogs/news/texniers-le-dahlia-1909?srsltid=AfmBOoq5i544eLo6jXZ-Y-4FWzXldF_uXdgvNZnG6HQGAYtfjwvHN6DY

- Bettina Verbeek, “Dahlien, die schönsten Sorten und ihre Pflege“, BLV, 2017

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)