Ah, the 18th century: a time of powdered wigs, elegance, perfumes, and… questionable personal hygiene? It’s easy for us modern folk—with our rain showers, scented soaps, and expensive bath bombs—to scoff at the idea of physical cleanliness back then. But was personal hygiene in the late 18th century really as dreadful as it seems? Let’s take a look at the changing ideas about taking a bath, the related technical progress, and how one might soak in style during Jane Austen’s day.

Glorious Bathing, Dangerous Bathing – A (Very Brief) Splash Through History

The concept of bathing and the use of water for hygiene purposes can be traced back several thousand years:

- The earliest plumbing systems, discovered in India, date back nearly 6,000 years.

- The Romans were clearly fond of bathing: public bathhouses were popular with commoners, and the wealthy had entire rooms dedicated to splashing about in style.

- In medieval and early Renaissance Europe, public bathhouses were still the go-to, while the rich enjoyed private bathing—often with a large wooden tub right in their bedroom. The ‘bathroom’ as we know it didn’t exist.

It was in the 16th century that the popularity of public bathhouses in Europe declined. From around 1550 to 1750, people believed that washing oneself all over was strange, sexually arousing, and even dangerous. Hot water, some feared, would open pores to germs in the water. Henry VIII closed down the bathhouses of London, as they were considered places of ill repute.

Of course, body odour wasn’t attractive. People regularly washed body parts, used perfumes, and made sure to wear clean underwear. It was, after all, the cleanliness of the clothing that was thought to reflect the soul of an individual. But washing the body all over in hot water was just not believed to be a good idea in those days. Bathing and personal hygiene were two very different things.

The Return of Bathing in the 18th Century: Now with Medical Justification!

In the middle and late 18th century, the medical uses of water came back into the focus of British writers. Immersing the body in water was no longer connected to contamination and diseases. It was argued that frequent bathing might indeed lead to better health. However, these new ideas about bathing focused on bathing for medical reasons, such as the treatment of fever and other illnesses. Thus, washing at home became a new medical trend for the wealthy. Cold water was initially preferable, while bathing in hot water was still considered risqué.

How to Take a Medical Bath in Jane Austen’s Day

If you’ve seen the 1987 film adaptation of Northanger Abbey, you may already be familiar with the customs of public medical bathing of the day. Here is what you need to know:

- The King’s and Queen’s Baths, overlooked by the rear of the Pump Room, offered public bathing hours. The recommended bathing hours were between 6 am and 8 am. The bath was open to the weather and offered little privacy.

- The more elegant Cross Bath catered to the wealthy. Here, bathers could drink hot chocolate and listen to musicians playing in the gallery. Naturally, there were separate bathing days for ladies and gentlemen.

- In all establishments, bathers sat in the water up to their chest, and for no longer than 15 minutes. The water temperature was a constant 46.5 degrees Celsius.

- Bathers remained modestly dressed. Men wore shirts and drawers; ladies wore linen shifts.

Technical Progress Brings on the Water (and Sometimes also Fish)

Fortunately for the improvement of personal hygiene, technical progress led to better access to cleaner water in the cities. As early as the first decade of the 17th century, The New River Company, a privately owned water supply company, brought fresh water to more than 1,000 customers in London via pipes. From the 1670s, several new waterworks were established and reached many households. In Georgian London, water flowed from the tap for a few blissful hours on ‘water day’. Servants would fill up the cistern and pots. As the water wasn’t filtered, it was quite likely to find fish and other small creatures in the pots.

The Actual Act of Bathing (for the Rich)

Even with more water available, taking a bath wasn’t easily done. It required the hard work of many servants:

- Water had to be heated downstairs, lugged upstairs in buckets, poured into the tub, then lugged back downstairs again once used (hopefully without sloshing it all over the parquet).

- Wealthy households had specialised ‘water-men’ for this backbreaking work.

Nevertheless, the rich embraced the new trend for bathing. Richly ornamented bathtubs made of marble were the height of luxury. Others preferred portable wooden or metal tubs. While bathing, it was common to cover oneself with sheets. To keep bathers warm, these linen sheets could be suspended over the hot tub to create a kind of miniature sauna. Bathers also wore clothing while sitting in the tub. They would be dunked with warm water, rubbed with flannel cloths, and treated with soap solutions.

By the End of the Regency Period… Still No Happy Ending

By the end of the Regency period in 1821, daily bathing was not yet part of daily life. While famous dandy Beau Brummell was instrumental in bringing daily bathing into fashion for the wealthy, average people couldn’t afford to do so. Bathing on Saturday evening was a widespread practice—with one bathtub for all, and the head of the family or the most senior servant going in first.

It was by the 1860s that plumbed-in baths became more available. Until then, most people had to make do day by day with what was available: a basin and water from a jug.

Related articles

Sources

- Anna (Austenised – All things Jane Austen): The King’s and Queen’s Baths, at: https://austenised.blogspot.com/2011/05/kings-and-queens-baths.html, May 16, 2011

- Erin Blakemore: How to Bathe Like a 18th-Century Queen, at: https://daily.jstor.org/how-to-bathe-like-a-18th-century-queen/, March 8, 2017

- Joanna Marschner: Baths and bathing at the early Georgian court,Furniture history. 1995, Vol. 31, 23-28

- Lucy Worsley: If Walls Could Talk: An intimate history of the home; Faber & Faber: 2012

- Ruby News: “Jane Austen’s Bath Spa Experience “; Strictly Jane Austen, at: https://strictlyjaneausten.com/jane-austens-bath-spa-experience/, 29/05/2024

- Soaking It In: The History of the Bathtub By Bath Tune-Up, at: https://www.bathtune-up.com/blog/soaking-it-in-the-history-of-the-bathtub/, June 14, 2023

- www. Wikipedia.com

Photos taken at:

- Burton Constable Hall, Skirlaugh, Hull HU11 4LN, UK

- Château de Chamerolles, Gallerand, 45170 Chilleurs-aux-Bois, France

- Château de Vaux, Font aux Dames, 10260 Fouchères, France

- Château de Champs-sur-Marne, 31 Rue de Paris, 77420 Champs-sur-Marne, France

- Château de Fontainebleau, 77300 Fontainebleau, France

- Château de Valençay, 2 Rue de Blois, 36600 Valençay, France

- Bathing Hall, Badenburg, Schloß Nymphenburg 205, 80638 Munich, Germany

- Wimpole Hall, Arrington, Royston, Cambridgeshire, SG8 0BW, UK

- Felbrigg Hall, Felbrigg, Norwich NR11 8PR, UK

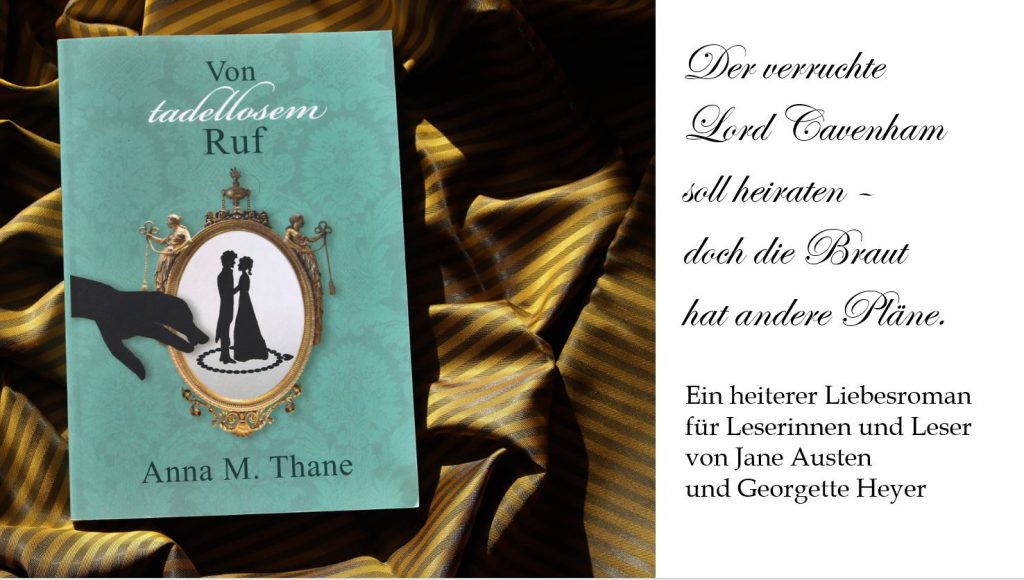

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)