Since the mid-18th century, England had been the centre of the optics industry, due to the work of instrument-maker John Dolland (1706-1761). Dolland manufactured small ‘achromatic’ telescopes with high-quality lenses made of flint glass (instead of the inferior crown glass). His products were in high demand from astronomers all over Europe. This began to change, when a poor man’s son, who had had a lot of bad luck in his youth, met the Bavarian Prince Elector.

Since the mid-18th century, England had been the centre of the optics industry, due to the work of instrument-maker John Dolland (1706-1761). Dolland manufactured small ‘achromatic’ telescopes with high-quality lenses made of flint glass (instead of the inferior crown glass). His products were in high demand from astronomers all over Europe. This began to change, when a poor man’s son, who had had a lot of bad luck in his youth, met the Bavarian Prince Elector.

Learning forbidden!

Death and Disaster didn’t mean well with young Joseph Fraunhofer, a Bavarian boy born in 1787. He was the youngest child of a poor glass grinder. Death claimed his parents and most of his siblings before Joseph had completed his 12th year of life.

Joseph had an unusually strong thirst for knowledge, especially science, but a formal education was out of his reach. He was instead apprenticed to the rather Dickensian Munich mirror maker and lens grinder Philipp Anton Weichselberger in 1799. Unfortunately, Weichselberger didn’t believe his apprentice should see further than the end of his nose. He forbade Joseph to attend Sunday school which provided education outside the trade. He also refused the boy a reading lamp at night, so Joseph was unable to study the science books he was so interested in.

Then, in 1801, Disaster stroke: Weichselberger’s workshop collapsed during restauration work, burying everything under rubble – including Joseph.

The fairy tale begins

People hurried to the rescue. Weichselberger’s wife was found dead, but after 4 hours of difficult rescue work, the boy was saved without serious injury. He had been protected from death by a cross-beam.

The miraculous rescue was much to the delight of Prince Elector Maximilian Joseph IV of Bavaria, who had come to inspect the scene of the accident. He invited Joseph to his castle, Nymphenburg palace, and put him in the care of his advisor, industrialist Joseph von Utzschneider (1763-1840).

From apprentice to partner

Utzschneider appreciated Joseph’s quick understanding and thirst for knowledge. He helped him to pursue a proper education alongside his practical training. In 1806, Utzschneider introduced Joseph into a leading glassmaking institute at Benediktbeuern / Bavaria, founded by inventor Georg Friedrich Reichenbach (1771-1826). Reichenbach took an interest in Joseph’s career, and he and Joseph became close friends.

At Benediktbeuern, Joseph discovered the art of making fine optical glass, and he invented precise methods for measuring optical dispersion. By 1809, Joseph managed the mechanical part of the Optical Institute, and he also became a junior partner of the institute.

Workshop equipment. On the left: protective mask made of wood and leather for workers at the glass-kiln

Usurping the British market of optical lenses

The lenses Joseph produced were of outstanding quality. He also developed fine optical instruments. His telescopes were of such high quality that astronomers all over Europe wanted them for their research, considering them even better than those of astronomic giant William Herschel (which rather infuriated his son John; more about John Herschel in a moment).

Michael Faraday tried – in vain – to produce the fine glass that came from Benediktbeuern himself. Reputedly, England offered Joseph’s Optical Institute 25.000 pounds if they shared the secret of glassmaking.

Due to the high-end optical instruments form Benediktbeuern, Bavaria overtook England as the centre of the optics industry.

Scientific success

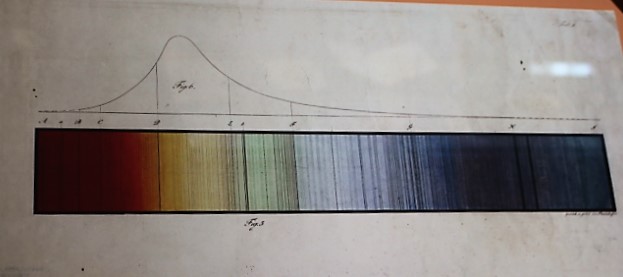

Besides almost single-handedly founding glass technology and changing glass production from a craft to a science, Joseph did considerable research on light. He is credited with discovering the so called Fraunhofer-lines – a set of spectral absorption lines – in 1814. Fraunhofer never knew it, but he prepared a foundation for atomic spectral analysis and astrophysics.

While Bavaria was slow to recognize the scientific work of a seemingly mere ‘technician’ lacking formal education, Fraunhofer’s fame spread in Britain. The Edinburgh Journal of Science published his discoveries. Eminent scientists such as Thomas Young (1773-1829) and John Herschel (1792-1871) studied his work. Fraunhofer’s technique of seeing the spectral lines became incorporated into British optical textbooks by the late 1820s.

Joseph discovered and studied the dark absorption lines in the spectrum of the sun known today as Fraunhofer lines. He mapped the relative positions of 574 of these lines. Photo: Solar spectrum in colour, around 1823.

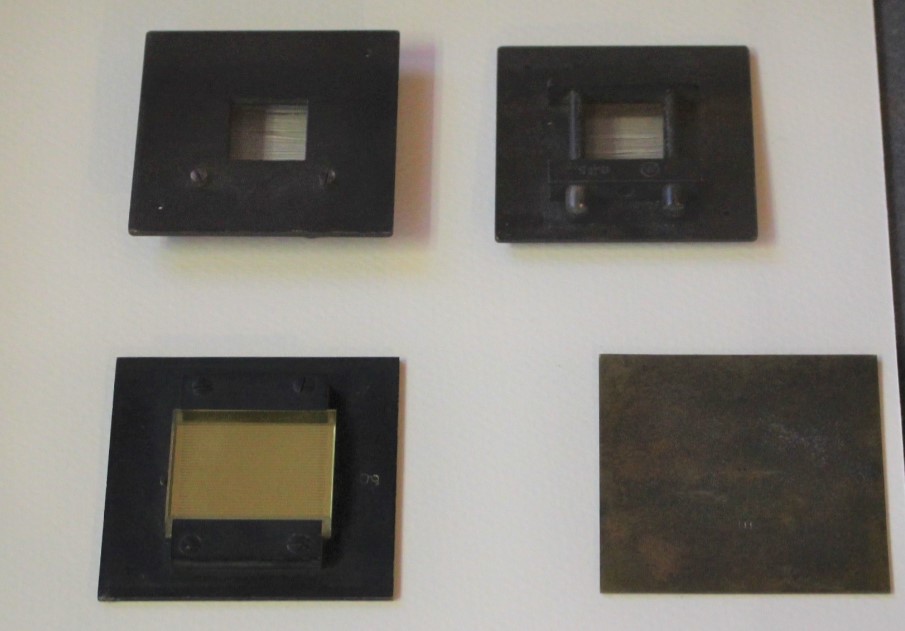

Joseph’s diffraction gratings: Light is diffracted by the slits and dispersed into colours even better than by a prism.

British visitors try to discover the secret

In 1824, John Herschel decided to the Optical Institute in Bavaria, and to discover the secret of Joseph’s success. On his way, Herschel met William Henry Talbot Fox (1800 – 1879, later known as a photography pioneer). At this time, Herschel already was a scientific giant, and Talbot Fox, despite his young age, had published six papers in mathematics.

Together they travelled to Benediktbeuern, trying to worm the secret out of Joseph. They spent an agreeable dinner together in September 1824, they discussed science, and Joseph amiability showed them how to see the set of spectral lines. He also gave them a prism. His secret, however, he kept to himself.

Nevertheless, the meeting ignited Talbot Fox’s interest in the physical sciences and turned it towards research into light and optical phenomena. Talbot Fox kept up a correspondence with Joseph, and both he and Herschel ordered prisms, achromatic objectives and lenses from him after their return to England.

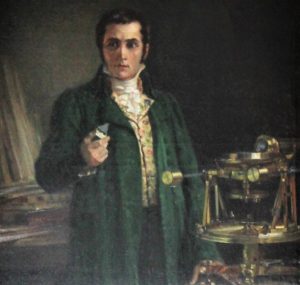

Joseph Fraunhofer demonstrates the spectroscope to Georg Reichenbach and Joseph Utzschneider (painting by Rudolf Wimmer).

Fame!

Joseph’s work eventually earned him an honorary doctorate in 1822. In 1824, the poor man’s son was awarded the Merit Order of the Bavarian Crown, raised into personal nobility (with the title “Ritter von”, i.e. knight), and made an honorary citizen of Munich. John Herschel awarded Joseph an associate membership in the Astronomical Society of London in 1825.

Death

Joseph fell ill at the end of 1825. The heavy metal vapours of the glassmaking production had poisoned his body. He died of tuberculosis in June 1826 at the age of only 39. His friend and sponsor Georg Reichenbach had died two weeks earlier in an accident, but because of Joseph’s bad health Georg’s death had been kept from him. Joseph and Georg were buried in adjacent graves at the Old South Cemetery in Munich.

The Quarterly Review in Britain mourned Joseph’s death: ‘Bavaria has thus lost one of the most distinguished of her subjects, and centuries may elapse before Munich receives within her walls an individual so highly gifted and so universally esteemed.’

Watch videos about spectral lines and Joseph Fraunhofer here: https://youtu.be/eSMhVDQtPD4?t=3 (in English) and here: https://youtu.be/XLMEdL2D67w (in German)

Related posts:

- The Man Who Understood Why Airplanes Fly (The Origin of Now (Part 3)

- Sports Equipment: Roller Skates (The Origin of Now: Part I)

- Your Challenge: Equip the Army with Small-Arms between 1793 and 1815

- The Letter Copying Press and Mr Watt’s Secrets Recipes for Ink and Liquor (The Origin of Now: Part 4)

- Panoramic Scene Wallpaper for the Fashionable Home of the Regency Period

- Forecasting the Weather in the 18th Century

- Smuggling Moonshine

- Becoming Alexander von Humboldt – A Budding Explorer in Georgian England

- The Reichenbach Case – Industrial Espionage at Boulton & Watt

Sources

- Moritz von Rohr: „Joseph Fraunhofer. Eine Biographie: Leben, Leistungen und Wirksamkeit“; Severus, 2011.

- J.C.D. Brand: „Lines of Light”; CRC Press, 1995.

- The Edinburgh Journal of Science, July 1829.

- Professor Larry J Schaaf (Project Director): „The correspondence of William Henry Talbot Fox, De Montford University Leicester / University of Glasgow.

- Myles W. Jackson: „Spectrum of Belief: Joseph Von Fraunhofer and the Craft of Precision Optics”; The MIT Press, 2000.

- Kitty Ferguson: „The Glassmaker Who Sparked Astrophysics. His curious discovery, 200 years ago, foresaw our expanding universe”; Nautilus, March 20, 2014.

- Stefan Hughes: „Catchers of the Light: The Forgotten Lives of the Men and Women Who First Photograped the Heavens”; ArtDeCiel Publishing, 2013.