Amelia Jane Murray (1800-1896) was an amateur watercolourist. Between 1820 and 1829, she painted fairies as tiny female figures dressed in neoclassical garments, sitting among flowers or riding on insects. Her watercolours, though never exhibited during her lifetime, have enchanted millions since they were published in 1985. The reasons behind Amelia’s fascination with fairies remain speculative. In this post, I offer a new interpretation of the influences on Amelia’s art based on the socio-cultural circumstances of her childhood and youth.

From Antiquity to Fairies: The Beginnings of a New Art Movement

During the 18th century, academic painting was characterised by a strong emphasis on themes of classical antiquity, with ideals of reason and order playing a central role. However, by the late 18th century, a new artistic movement emerged, aiming to explore different concepts: individualism, irrationality, a spirit of rebellion, and an emotional response to nature. Artists began seeking exotic or mystical subjects, often turning to the rich heritage of ancient British culture, such as druids, Celts, and fairies, or to the somewhat more recent works of Shakespeare. This trend quickly gained momentum and inspired amateur artists like Amelia Jane Murray.

The interest in national cultural heritage might not have flourished as it did without the efforts of John Boydell, a prominent London printmaker. He initiated a project aimed at fostering a British school of history painting. In 1786, Boydell hosted a dinner for eminent artists, including Joshua Reynolds, Benjamin West, Angelica Kauffman, George Romney, and Henry Fuseli, commissioning them to create scenes from Shakespeare’s plays. These paintings were to be exhibited in a dedicated gallery, with engravings sold in sought-after print folios. The so-called ‘Shakespeare Gallery’ was a success and marked the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. Shakespearean subjects became a focal point of the national school of British art.

Shakespeare was the primary influence on fairy painting, but fairies also appeared in the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Edmund Spenser, and John Milton. In 1812, the Brothers Grimm published their collection of German folk tales, which in turn influenced other collectors. This led to an ethnocentric spirit of romantic nationalism, where the celebration of language, history, and national culture became an inspiring ideal for artistic expression. The 18th-century book market swiftly embraced the trends for romantic literature and the revival of interest in traditional folk stories. Today, the Romantic Movement is considered the cradle of fairy art, which reached its zenith during the Victorian era.

Amateurs Embrace Fairy Painting

It is little wonder that amateur artists took up fairy painting. Watercolour painting, regarded as a suitable pursuit for genteel young ladies, was seldom published or exhibited, making it difficult to ascertain how many amateur artists painted fairies—particularly when their governesses were ensuring they adhered to appropriate topics. Fortunately, Amelia Jane Murray’s (1800–1896) works were first published in 1985, shedding light on her contribution to this genre.

A Precursor of Flower-Fairy Painting: Amelia Jane Murray

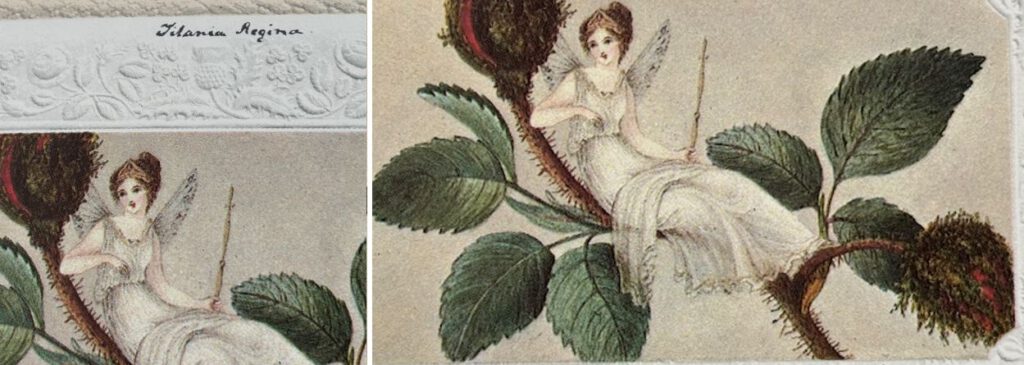

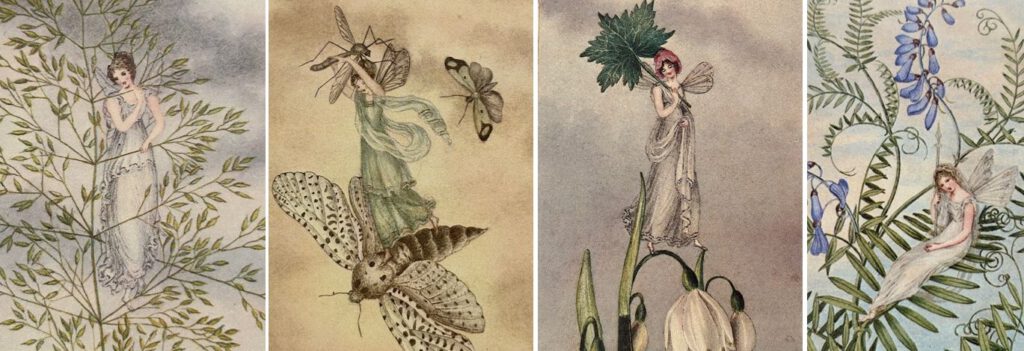

Amelia, a niece of the 4th Duke of Atholl, painted fairies between 1820 and 1829. Her delicate compositions, never exhibited or published during her lifetime, depict fairies as tiny, elegant ladies dressed in neoclassical garment or dresses of the Regency period. They are often portrayed sitting amongst flowers or riding insects, feathers, or birds. Some are shown using seashells as boats or playing with human objects such as snuff boxes or thimbles. In one painting, a fairy interacts with a ship. Amelia never depicted them interacting with humans. While her depiction of flowers and insects is in a scientific style, her fairies remind me of the female figures of 18th-century fashion plates. Some fairies are depicted posing like mannequins, while others use blossoms or insects as head-dresses. Today, Amelia Jane Murray is recognised as a precursor to flower-fairy painting.

Amelia’s Biography

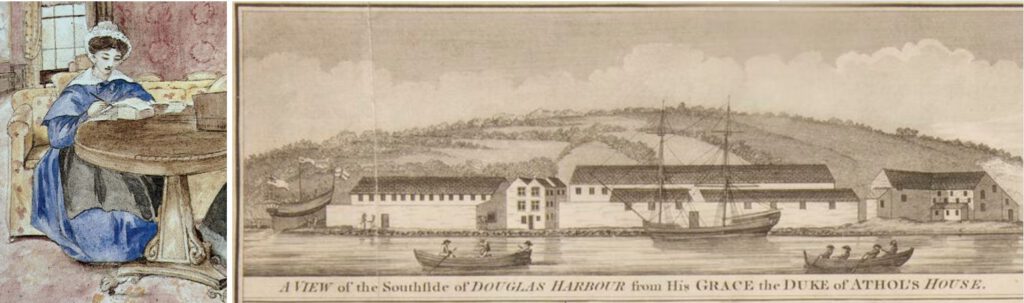

Amelia Jane Murray was born in January 1820 on the Isle of Man. Her father, Henry Murray, was the younger brother of the 4th Duke of Atholl. He was the Lieutenant-Colonel of the Royal Manx Fencibles and died unexpectedly in 1805. Amelia had five siblings. She grew up at Mount Murray Estate on Ais Hólt-Hill, near Douglas. Due to her family connections, she took part in events at Castle Mona, the private home of the 4th Duke of Atholl in Douglas. Amelia had lessons in painting, probably from a professional artist who visited the island. She began painting fairy art in 1820 and stopped when she married in 1829. Her husband, Sir John Oswald of Dunnikier, was a cousin who had distinguished himself in the Napoleonic Wars. He was twenty-nine years her senior and a widower with six children. Amelia moved to his home in Fife, Scotland, and they had two children together.

Influences on the Fairy Art of Amelia Jane Murray – Revisited

The reasons behind Amelia’s fascination with fairies remain speculative. Many scholars have suggested that the fairy lore of her birthplace, the Isle of Man, may have influenced her. Building on their work, I offer my own interpretation of the influences on Amelia’s art in this post.

Influences: The Napoleonic Wars

Amelia’s birth and upbringing took place during the Napoleonic Wars, and it is fair to assume that her outlook and beliefs were shaped by this tumultuous period. Events from her childhood and adolescence would also have influenced her artistic activities during the years 1820–1829.

Residing near Douglas Bay, Amelia would have witnessed ships like His Majesty’s Schooner HMS Alban anchoring nearby. Furthermore, approximately 60 to 70 sailors and Royal Marines from the Isle of Man fought at Trafalgar, including John Quilliam, First Lieutenant of the Victory. Their stories would have been widely recounted. During the war, the Isle of Man also raised volunteer forces, such as the Manx Yeomanry Cavalry (active until 1825). Additionally, the Royal Manx Fencibles were in service until 1810. The sailors and officers who came to the island brought the typical garrison port pursuits, and when off duty, they would socialise with the local gentry.

Amelia’s life was far from sheltered. She grew up amidst an unstable political climate, and her father served as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Manx Fencibles. It is highly likely that the war affected her, and she might have missed a father to console her. Did she occasionally seek solace in an imagined fairy realm?

Influences: Theatre and Fine Arts

The influx of soldiers and sailors brought prosperity to the town of Douglas. Theatres, exhibitions, a circulating library, and concerts offered refined entertainment. Leading theatre companies visited, staging plays by Shakespeare, Sheridan, and their contemporaries. Even the renowned actor Edmund Kean graced the town with his performances. It is plausible that Amelia had the opportunity to see the plays, including side shows and pantomimes that may have featured fairies. She would have had easy access to books with Shakespeare’s plays and poetry. Moreover, through her connections to Castle Mona, the private residence of her uncle, the 4th Duke of Atholl, she might have had access to a print folio of the Shakespeare Gallery.

Amelia usually didn’t add titles to her paintings. The exception is a painting of a fairy holding a sceptre and wearing a tiara, sitting on a rose. This painting is titled “Titania Regina”. Titania is the Fairy Queen in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It proves that Amelia was inspired by Shakespeare’s work.

Influences: Botanical Illustrations

Botanical studies, including drawing and floral embroidery, were an important part of the cultural education of upper-class women in the late 18th century, encouraged by the interest in botany shown by female members of the royal family. This trend was supported by the family of the Duke of Atholl. Lady Charlotte Murray (1754–1808), Amelia’s aunt, created no fewer than 267 miniature botanical illustrations. Having a scientific interest in flowers, she arranged them according to the System of Linnaeus in a specially adapted box. She was also the author of The British Garden. The Duke’s family often visited the Isle of Man, and it is easy to imagine Lady Charlotte sharing her love of botany with young Amelia.

In 1819, Le Langage des Fleurs by Charlotte de la Tour was published in Paris, becoming an instant sensation across Europe. It may well have inspired Amelia, who began her fairy art in 1820.

Amelia painted flowers and insects in a realistic, nearly scientific way. It is likely that she had an interest in botany and took pains to achieve a scientific depiction. These, she contrasted with ethereal fairies, looking translucent and delicate. Thus, science meets mysticism in her paintings, making Amelia a true artist of the Romantic movement.

Influences: Political Conflicts

Amelia was a member of the prestigious Murray family. Her uncle, the 4th Duke of Atholl, was the manorial lord from 1765 to 1828 and served as Governor from 1793 to 1830. However, his relationship with the islanders became strained over time. By the time Amelia reached adulthood, tensions within some circles of Manx society were high. These circles resented the Duke, believing he and his family used their positions solely for personal gain, earning them the epithet “grasping Murrays”. Matters escalated into the ‘Potato Riots’ of 1825, when the Duke’s nephew, appointed as Bishop of the Isle, tried to extract more tithes from potato farmers. The militia was called in, and the bishop and his family had to flee to Castle Mona for safety. These events led to the Duke’s departure from the Isle of Man in 1825, and his role as manorial lord ended in 1828.

Amelia was undoubtedly aware of these tensions. She is likely to have heard a first-hand account of the riot and may have even witnessed the bishop’s family arriving at Castle Mona in terror.

We might wonder if Amelia’s marriage in 1829 was a consequence of the Duke of Atholl’s departure. She probably was to lose her home, and when her cousin, Sir John Oswald of Dunnikier, asked for her hand, she accepted to start a new life at his home in Dunnikier, Fife. With her marriage, Amelia stopped painting fairies. But she continued to paint watercolour portraits of her children and family.

Conclusion

We will never know for certain what motivated Amelia to paint fairies, nor why she stopped in 1829. My interpretation is that she was influenced by Shakespearian scenes of theatre and fine arts, the vogue for botanical illustration, and possibly used the fairy world as an escape from the uncertainties of war and political conflict. I have proved that Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream was the inspiration for at least one of her paintings. By using scientific and mystical elements in her art, she is a true painter of the Romantic movement.

Perhaps she painted fairies as a way of remembering her father. The Manx meaning of the word “fairy” is ‘little family’. Fairies are often interpreted as spirits of the dead, or as protectors of vanished ancestors.

I hope Amelia found happiness and companionship in her marriage, allowing her fairies to remain on the Isle of her youth.

Related articles

Sources

- A. W. Moore: A History of the Isle of Man, Volume I, London, 1900

- Nathaniel Jefferys: A Descriptive and historical account of the Isle of Man, 1808

- April Agnew-Somerville: “A Regency Lady’s Faery Bower – ‘A Private View of Fairyland: Amelia Jane Murray 1800-1896; William Collins, 1985

- www.wikipedia.org

- Bill Kelly: Chrononhotonthologos, Phantasmagoria. Cotillions and Supper Entertainment in the Isle of Man 1793-1820; undated; at: http://www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/history/theatre/1800s/index.htm

- Frances Coakley (editor): A Manx Notebook; an electronic compendium of matters past and present connected with the Ilse of Man; at: http://www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/

- Sarah Maria Murray: A Memorial of the Isle of Man, 1825, at: http://www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/fulltext/mem1825.htm

- The papers of the Dukes of Atholl relating to their administration of the Isle of Man, at: https://imuseum.im/search/collections/archive/mnh-museum-272779.html

- Manx Advertiser, at: https://www.imuseum.im/newspapers/

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)