In this post:

- The marvel of the panoramic scene wallpaper

- Technical innovations of the early 19th century

- Keeping the craft alive

Wallpaper has been known since at least the 15th century. Starting as a rare luxury item for the elite, wallpaper became more popular in England at the beginning of the 18th century. By then, wallpaper had become a cheap alternative to tapestry or panelling. 1712, the government even imposed a tax on it. Despite the taxation the demand for wallpaper grew in the mid-18th century.

Most wallpapers had been brought to England by the East India Company from China, where Chinese artisans produced hand-painted, dedicated wallpaper for their rich English customers. By the end of the 18th century, producers in France specialized in printed wallpaper became an important competitor on the market.

European wallpaper was printed on sheets using woodblocks. Around the end of the 1790ies, two French wallpaper producers decided to further the idea of woodblock-printed paper. The two men were Joseph Dufour, based in Lyon, famous for its textile industry, and Hartmann Risler (later to become Zuber & Cie.) in Rixheim, Alsace. They founded their respective companies in 1797, aiming at the market of the middle class. Soon, they specialised in special printed panoramic scene wallpaper. They hit on a gold mine.

The marvel of the panoramic scene wallpaper

Panoramic scene wallpaper was a little bit like today’s photo wallpaper. It was inspired by the full-circle panorama used for city entertainment, which had become popular on the Continent and in England around 1800 (read all about the panorama here.)

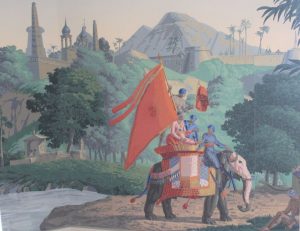

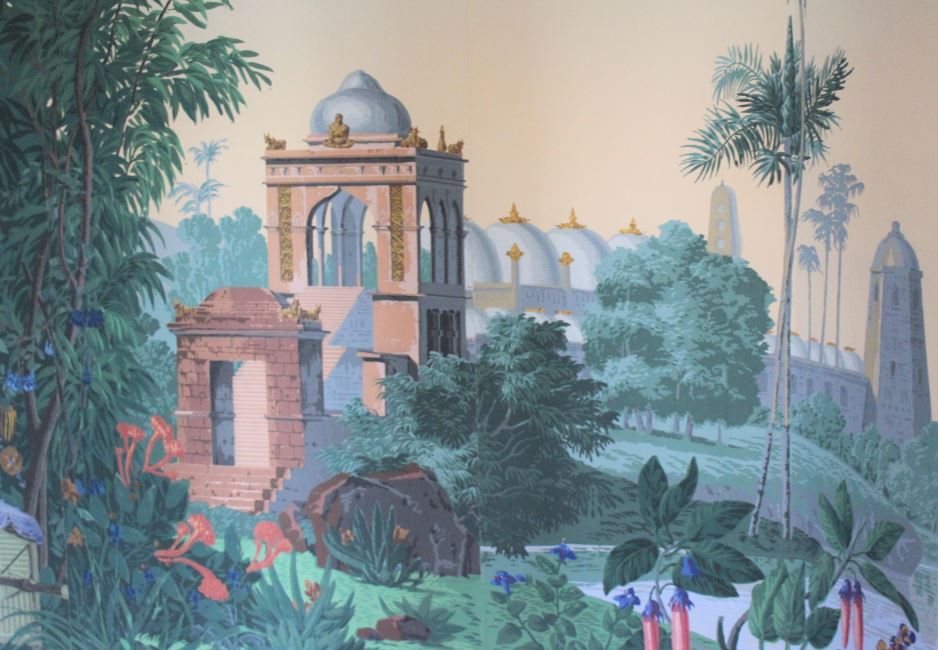

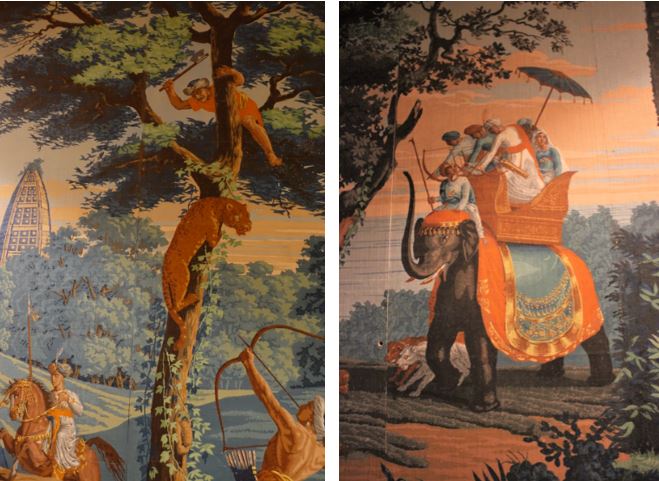

A reprint of the panoramic scene ‘L’Hindoustan’. You can see it in the Garden Room of Basildon Park / England. It was originally designed by Antoine Pierre Mongin. To create the wallpaper 85 colours were applied with 1, 265 wooden blocks.

The designs for the panoramic scene wallpaper were often inspired by the Grand Tour of the rich and expeditions to foreign places such as South America and India. Dufour created a panorama featuring Captain Cook’s South Seas expeditions, and Zuber came up with Les Vues de Suisse and L’Hindoustan. They also designed wallpapers featuring mythological scenes and neoclassical motifs.

One of the artists working for Zuber was the Parisian landscape painter and engraver Pierre-Antoine Mongin (1761 – 1827). He created the panoramic scenes L’Hindoustan (1807), La grande Helvétie (1814), La petite Helvétie (1818), Les Lointains (1825). The artist had never been to India, but based his imaginary landscape on a series of 144 prints called ‘Oriental Scenery’ published in the late 18th century.

Technical innovations of the early 19th century

Printing the paper by woodblock rather than painting it by hand allowed the wallpapers to be created in greater quantity, and thus to a more affordable cost. Still, it was a complicated process:

- Designs for a new panorama were done in pencil, watercolour, gouache, or even wool, gravel and straw.

- As grounding, a uniform base colour had to be applied to the paper before the pattern was printed onto it. Applying the grounding was done by several persons with large brushes. The grounding process was mechanized from the 1830ies.

- Once the grounding had dried, the design was printed with carved wooden blocks one colour at a time. Drying the paper could take up to a day, and only then a new colour could be added into the design. A design could consist of ten to over a hundred colours.

Watch a video about the making of a printed wallpaper: https://youtu.be/4EN5xsAWcLU

Printing wallpaper profited from new technics from around the 1820ies:

- The intaglio printing technique that was already used in the textile manufactories since 1780 for the Toile de jour-fabrics was applied to the production of printed wallpapers in 1826.

Copper rollers engraved with a sunken in relief were rolled over a paper roll, solving the problem of the visible join between each block print. - A machine to produce endless paper was introduced to the wallpaper production in the 1830ies, putting an end to sticking single sheets together.

The first machine to produce ‘continuous paper’ had been patented in 1799 by Nicolas Louis Robert, and further developed in England. The machine was the forerunner of the Fourdrinier Machine, patented in 1801. Though the Fourdrinier Machine could produce endless paper rolls the innovation spread slowly.

Cupid and Psyche, Dufour and Cie, ca. 1816, desigend by M. J. Blondel and Loius Lafitte (The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester)

Keeping the craft alive

Up until the industrial revolution, when more mechanical printing processes were invented, woodblock-printed wallpaper made up the majority of the market.

Up until the industrial revolution, when more mechanical printing processes were invented, woodblock-printed wallpaper made up the majority of the market.

Jean Zuber’s wallpapers earned him the National Order of the Legion of Honour, the highest French order of merit for military and civil merits. It had been established in 1802 by Napoléon. King Louis Philippe honoured Zuber in 1834.

Until today, Zuber still produces beautiful wallpaper as it was done in the past. If you happen to visit Rixheim / France, make sure to see the Musée du Papier Peint, 28 Rue Zuber.

Related posts·

Making watercolour-paper as it was done in the Regency period

Origin of Now, Part 4: The Letter Copying Press and Mr Watt’s Secrets Recipes for Ink and Liquor

The Girl, the Kite and the Eccentric Inventor

Sources

Musée du Papier Peint, 28 Rue Zuber, Rixheim / France

Basildon Park, Lower Basildon, Reading RG8 9NR, UK

Robert Khederian, Historic wallpapers: Why they’re different, and why it matters; Sep 1, 2016, 1:29pm EDT

France Today: Zuber: Wallpaper as Art; May 16, 2014

The Whitworth Art Gallery, Oxford Rd, Manchester M15 6ER, UK

Attinghman Park, Atcham, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY4 4TP, UK

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)