Brandy, tea, salt – these products are famed-famous as objects of smuggling in the 18th century. Did you know that Scottish whisky was an object of the illegal trade, especially between 1780 – 1823? Whisky was called ‘moonshine’ then, as it was illicitly produced at night in small cottages in the Highlands, and secretly transported by smugglers to harbours for further distribution.

Illicit Distillers

Distillers came from all social groups: farmers, workers, widows. The driving force behind illicit distilling and smuggling was poverty. The Highlands had low agricultural productivity, and hardly any crafts and industry. Thus, to gain a small additional income, thousands of illicit stills were operated in the glens abounding with fresh water and clean air. These stills were illicit as buying a very expensive license for distilling was out of reach for most people. To be engaged in illicit distillation, and to defraud the excise, was neither considered a crime nor a disgrace.

Setting up the business

Distilling whisky did not require full-time attention. It could be done at home, during the autumn month, after harvest. The illicit distiller-to-be would save some money by, e.g., working for a season in the industries of the large cities in the Lowlands, living there frugally, and then investing the saved shillings in the basic equipment. Buying a license for distilling as well was too expensive.

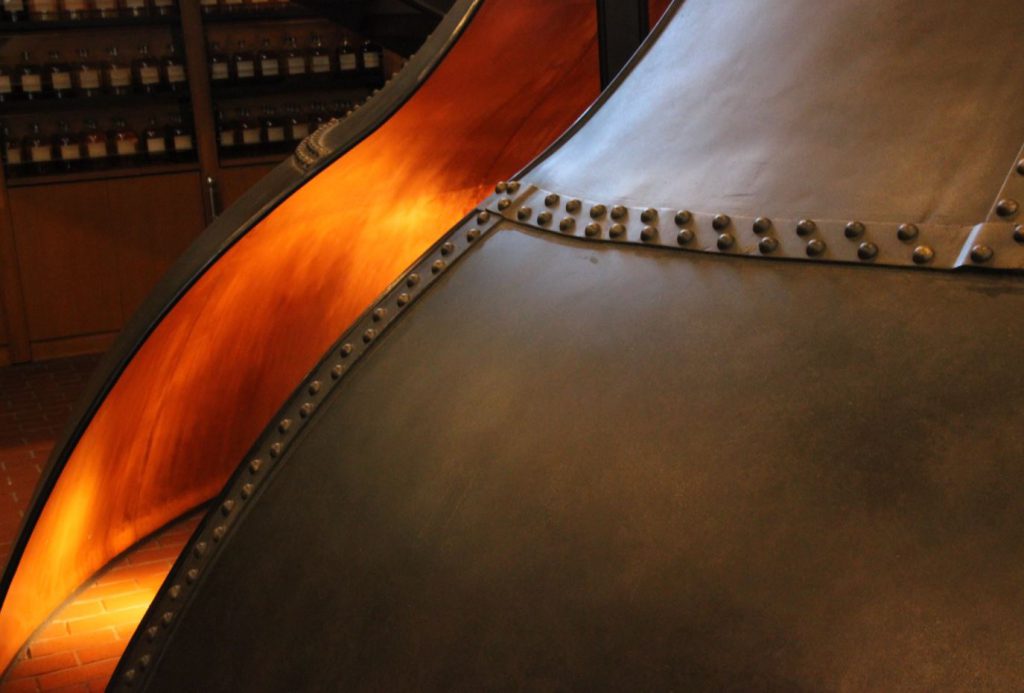

The complete apparatus for pot-still distillation cost less than 4 pounds. If you could go with the head of a still only and your own pot or kettle, you wouldn’t have to invest more than a few shillings. Additionally, you needed to buy materials which would cost about 15 – 20 shillings. Your gain might be from 3-6 pounds, depending on the price of whisky.

The drawbacks of the business

Producing illicitly had its disadvantages. You were unlikely to be able to gain the maximum monetary return for your effort:

- You were working at home, in limited space, and thus you hadn’t the store to hold supplies until the prices for your product rose.

- Farmers charged you a higher price for grain than in the ordinary market

- The distribution of the product was controlled by professional smugglers. It was them who dealt with retailers and customers

- There was always the risk of being discovered by excisemen. They would confiscate the product, and might also destroy your equipment (though they rarely did, as they were paid for delivering confiscated illicit whisky to the authorities).

All in all, distilling whisky wasn’t an easy way to become rich. But it would enable you to pay the rent.

Professional Smugglers

Whisky was usually smuggled by trained smugglers with long-term experience in illegal operations. Before dealing with whisky, they often had been successfully involved in subversive anti-Campbell and Jacobite activities, and had clandestinely imported products such as brandy, rum, gin, red and white wine, vinegar, olive oil, raisins, tobacco, soap, etc. They were excellently connected; landowners and local magistrates frequently tolerated if not even supported the trade.

Modus operandi

Professional smugglers travelled in large paramilitary bands. Their tactics included disguising as soldiers, and employing alert routines including optical signalling via fires, smoke, and flags. Less military-inspired was the setting up of phoney funeral processions to transport whisky in coffins or hearses. Some whisky containers were made to look like a person riding pillion behind a horse-borne man. The container even had a leather head to complete the illusion from a distance or in the twilight.

Women as smugglers

Special to the smuggling of Scottish whisky was the high number of female smugglers involved. They often operated near port towns and in broad daylight, right under the eyes of the authorities. E.g., women wore two-gallon ‘belly canteens’ made of sheet iron around their waist. Covered with the cloth of the dress, these looked like pregnancy bumps. Women also concealed bottles in unplucked dead geese. Another female activity related to smuggling was that wives of smugglers sent presents, such as veal, poultry, butter and – of course – whisky to the wives of excisemen; in return they were informed when the patrols would go after the smugglers.

Costumers and market conditions

As late as 1770, whisky was described as a ‘modern liquor’. It slowly became fashionable alongside brandy, ale, claret and gin. However, whisky became the most popular drink of the Scottish lower classes from around 1785, and even the most popular liquor of the Edinburgh and Glasgow High Society from around 1800. This was due to the better quality of the Highland whisky, as the illicit distillers had access to quality grain. But market success was also helped by the rising tariffs duties for brandy and claret as well as the interrupted trade during the Napoleonic Wars.

Silent supporters

The Highland magistrates and landowners had a lenient attitude towards illicit distillers. The distillers were tenants in the local area, having rents to pay. As a matter of fact, poverty in the Highlands was such that often only tenants involved in illicit whisky production were able to pay the rents. It is estimated that on some estates the rents could be tripled if the landowner turned a blind eye to distilling. Thus, many people in respectable positions would support the trade, such as Reverend Andrew Burns, minister of Glen Isla, who would keep his eye on the arriving party of excisemen, and then would warn every bothy that housed an illicit still.

Fiscal and legal background

Why was illicit distilling and smuggling so popular in Scotland? In 1707, the parliaments of Scotland and England were united and the English system of customs duties and excise was introduced into Scotland. This meant that duties on some products north of the border increased sevenfold. Additionally, a tax on malt, an essential ingredient of whisky production, was introduced in 1725. The price of grain kept rising in the decades of 1780-1820. All this helped spur on the illicit distilling of whisky – i.e. the distilling of whisky without a license. Producing whisky was legal – if properly licensed and taxed – until 1814. Then small stills of less than 500 gallons were prohibited. It’s little wonder that smuggling boomed.

After decades of fruitless efforts against the illicit whisky trade, a legislation legalising the distillation of whisky was introduced in 1823. Also, landowners were pressed to evict tenants who distilled illegally. These actions marked the beginning of the end of smuggling ‘moonshine’.

Related articles

Sources

T. M. Devine: The Rise and Fall of Illicit Whisky-Making in Northern Scotland, c. 1780-1840; The Scottish Historical Review; Vol. 54, No. 158, Part 2 (Oct., 1975), pp. 155-177

Charles MacLean and Daniel MacCannell: Scotland’s Secret History: The Illicit Distilling and Smuggling of Whisky; compiled and edited by Marc Ellington; Birlinn, 2015

Scottish History Online: The Smugglers and the Whisky Roads https://www.scotshistoryonline.co.uk/bridges/html/whisky.htm

Derek Cooper, Fay Goodwin: The Whisky Roads of Scotland; Hobhouse Ltd, 1982

Richard Platt: Smuggling in the British Isles: A History; The History Press, 2011

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)