Keeping circulating money under control was a tough job for both governments and merchants. Small-denomination coins for everyday transactions were scarce. In fact, coins had been in short supply in Britain for several centuries, but the shortage became particularly acute in the late 18th century. There were several reasons for this:

- A strong population growth rate between 1750 and 1800

- The Industrial Revolution brought about factories, whose large and ever-growing workforces had to be paid in cash

- A large number of counterfeit copper coins in circulation – some sources suggest that by 1786, two-thirds of the coins were counterfeit

What could be done to address the problem? Here are three more or less helpful financial instruments used in Britain and on the Continent:

1. Overstriking Foreign Currencies

To supplement the shortage of British silver coins, the Bank of England overstruck Spanish American 8-real coins between 1804 and 1811. These were issued with a value of 5 shillings. The coins were struck at the Soho Mint in Birmingham for eight year; however, all bear the date 1804. They were withdrawn from circulation between 1817 and 1818.

2. Cutting Coins

The Dutch West India Company addressed the coin shortage by cutting coins into “triangles” and stamping a new value on each piece. For example, Spanish silver pesos (valued at 8 reales each) were cut, and each smaller segment was given the value of 3 reales.

3. Issuing Your Own Tokens

As a private business owner or merchant, you could issue your own tokens to serve as coins for everyday transactions. The first of these tokens were issued in 1787 to pay workers. The Soho Mint was among the companies that produced such tokens on behalf of business owners. Using eight steam-driven presses, the mint could strike between 70 and 84 coins per press and minute. It is therefore unsurprising that, as an ordinary person, you would soon find a variety of designs in your purse. By 1795, a few thousand varieties of tokens were in common use in Britain.

However, the popularity and practicality of tokens varied over time. By 1802, the production of privately issued provincial tokens had ceased—only to resume a few years later due to a rise in the intrinsic value of copper. Privately minted token coinage was once again in high demand around 1811–1812. The situation escalated to the point that Parliament responded with “An Act to Prevent the Issuing and Circulating of Pieces of Copper or Other Metal, Usually Called Tokens” (27 June 1817). This legislation prohibited the manufacture, circulation, and passing on of private token coinage.

The Act included penalties: anyone who circulated or passed a token from 1 January 1818 onwards was to forfeit between 2 and 10 shillings per token, at the discretion of a Justice of the Peace. Persons who refused to give evidence in investigations related to the illegal circulation of tokens faced a heavy fine of £50.

Tokens issued by the Bank of England were excluded from the Act, as were those distributed to the poor in Sheffield and Birmingham. These latter exceptions were temporary, providing local authorities time to devise alternative forms of assistance. This grace period ended on 21 March 1823, after which even tokens for the poor in Sheffield and Birmingham were banned.

Attribution:

BrandonBigheart for the photograph; Ponthon for the token design; Boulton for the token manufacture; Ibberson for the token issue., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, June 27, 2013 for the photograph; December 1794 for the token minting. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7a/Conder_Token_Middlesex_DH342_obverse_and_edge_inscription.jpg

Related articles

Sources

- The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, 57 Geo. 3. c. 46: https://books.google.de/books?id=7GM0AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA246&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=token&f=false

- Staatliche Münzsammlung München, Residenzstraße 1, 80333 München, Germany

- Wikipedia.com

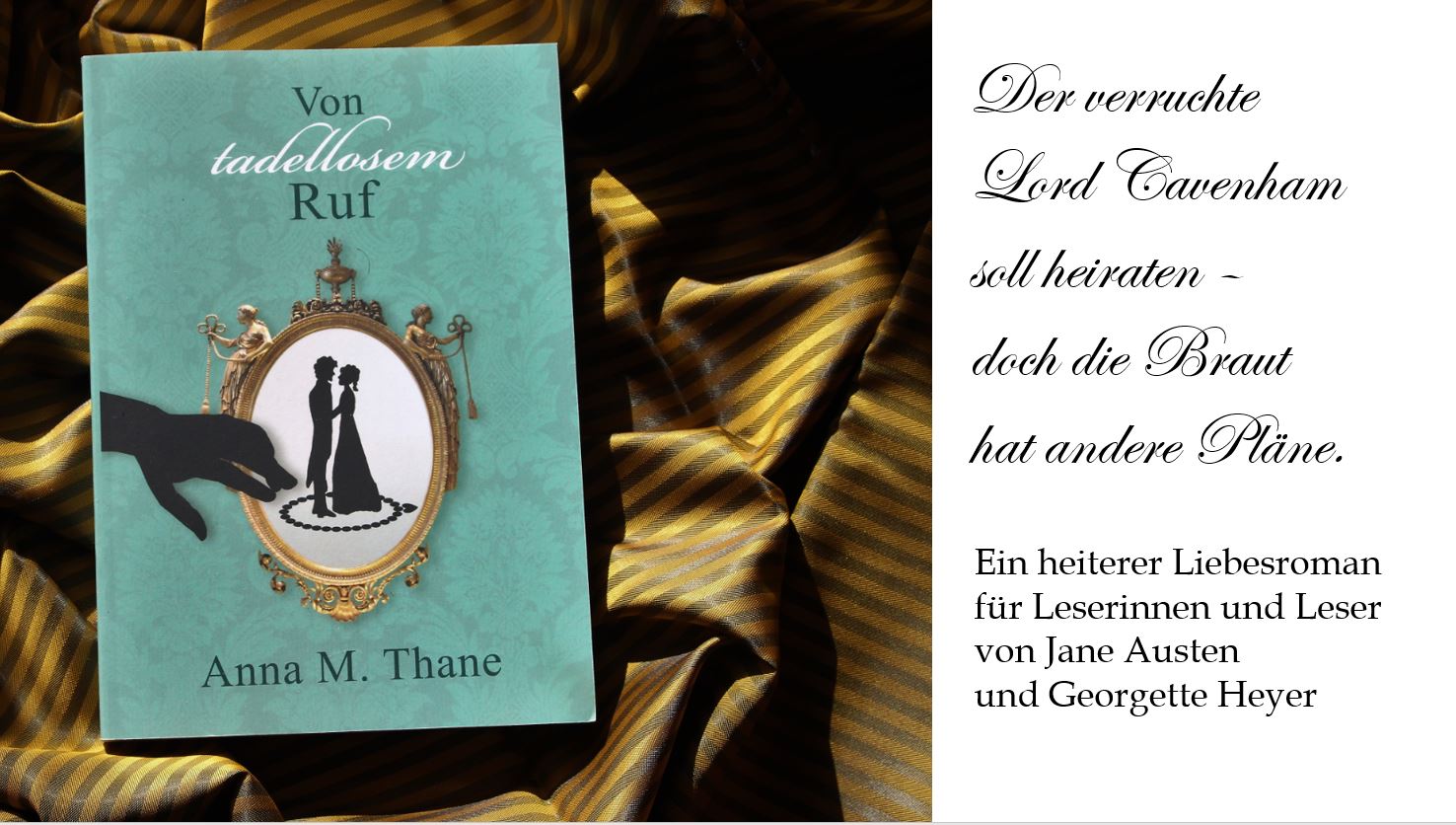

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)