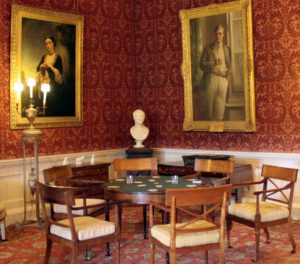

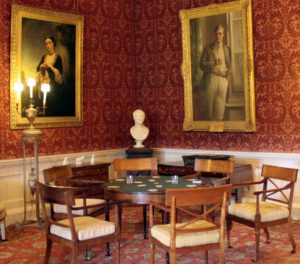

Gaming table in a country house. Would you have dared to play Whist with strangers?

Whist was one of the most popular card games in Georgian England. It began its career as a plain game for common men. With the rise of the coffee houses in London, the gentry picked up the game. Reputedly it was Lord Folkestone who brought the game into fashion in high society around 1728, when he adopted it as a challenging strategic card game requiring good memory, sympathetic partnering and psychological acumen.

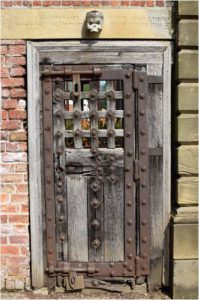

The rules of Whist were written down in Edward Hoyle’s “ A short treatise on the game of whist” in 1742. As early as this, methods of cheating were discussed. While Hoyle advocated fair play, the stakes at Whist could be high, and thus tempt many to force luck their way. Besides, cheating at whist is very easy. Continue reading →