The first steps towards the mechanisation of shoemaking were taken during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1810, engineer Marc Isambard Brunel developed a machinery that could mass-produce nailed boots for the soldiers of the British Army.

How well did he succeed?

According to Brunel’s biographer Richard Beamish, the engineer was moved to develop the shoe-making machinery after witnessing soldiers from the Peninsular War disembarking at Portsmouth. Talking to them, he learned that they had marched across northern Spain “with lacerated feet enveloped in filthy rags bound round with knotted strings.”

Mechanised mass-production, Brunel believed, could produce footwear quickly, cheaply and in good quality. Even more, it was resistant to fraudulence: Some ruthless contractors for shoes used to introduce clay between the soles of the shoes instead of thick leather in order to meet the weight requirement of their contract. Unsurprisingly, these shoes dissolved into mud when they became wet. Usually, they did not last a day’s march.

Marc Brunel developed a set of 16 machines that could mass-produce nailed boots for the soldiers of the British Army. The workforce of his manufactory consisted of disabled soldiers he employed with the assistance of the Invalid Department. These men – though unable to do harder work – were able to learn their tasks within in a few hours.

High-ranking visitors such as the Duke of York (Commander-in chief) and Lord Castlereagh (Foreign Secretary) came to visit the shoe manufactory in Battersea.

Production steps

First, soles were cut on an iron frame. Then, the inner sole was laid over the leather uppers which had been stretched and clamped to a cast-iron last. In the next step, the outer sole was clamped in places and pierced with holes by an awl. This mechanism was activated by a treadle that moved an iron plunger. The same plunger was then used to hammer in pins or nails that held the shoe together.

Brunel later added a machine that made the nails used in shoe production. He also invented a process to make the leather more durable.

Output and prices

Brunel’s machinery could produce shoes in 9 different sizes. The factory produced 100 pairs a day in 1810, and 400 pairs a day by 1812 with 24 workers.

In 1814, mechanically made shoes for soldiers cost between 6 s and 9 s 6 d a pair (about 3 daily wages of a skilled tradesman). Half boots could be bought for 12 s. The newly invented Wellington boot was available for 20 s.

It is said that Wellington’s soldiers at Waterloo wore boots made by Brunel at Battersea.

Decline

Brunel sold all his shoes to the military in 1814, but some quantity of shoes returned to his factory for issues of quality between February and April. Besides, mechanically made shoes were not considered equal to those that were hand-cobbled. One of the issues with mechanically made shoes was that were impossible to mend in the field – a significant fault in a time when things were mended instead of thrown away. The main value of Brunel’s shoes was in their initial durability.

After the end of the war in 1815, manual labour became cheap, and the demand for military shoes declined. Thus, Brunel’s shoe manufactory ceased business with a stock of about 80,000 pairs of boots. It was devastating for Brunel who claimed to have invested 15,000 pounds on building, machinery and material, most of it from his private money.

The industrialization of shoemaking began around 1830.

Related articles

Sources

Meaghan Walker: Standardized Footwear, invalid Labour, and the Technology of Production; Marc Isambard Brunel and the Battersea Shoe Factory; University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

Thom, Colin. “Fine Veneers, Army Boots and Tinfoil: New Light on Marc Isambard Brunel’s Activities in Battersea.” Construction History, vol. 25, 2010, pp. 53–67. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41613959. Accessed 26 Mar. 2020.

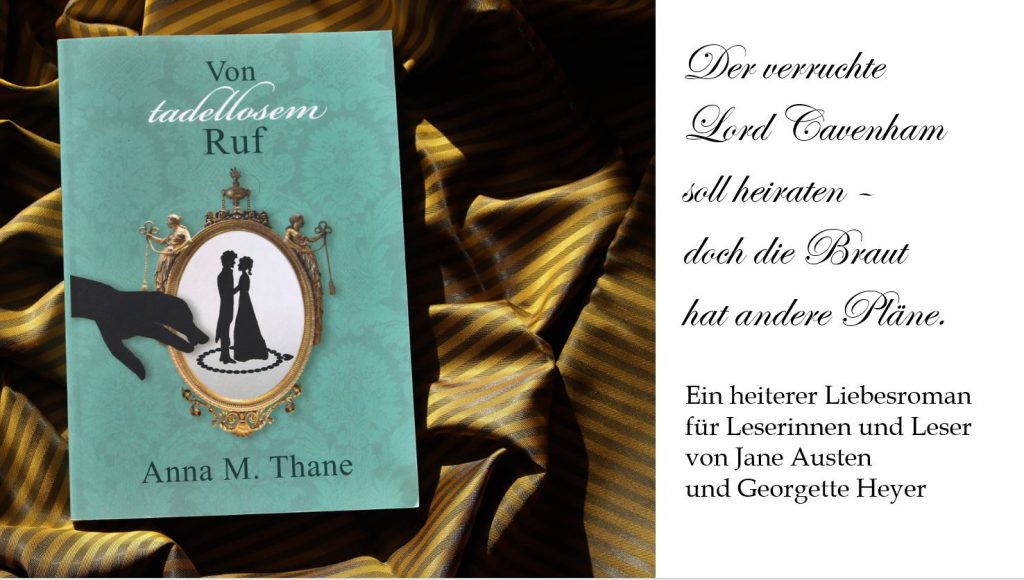

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)