Will there be rain, sun or snow within the next days? Should I plant my crops – or rather delay a journey? Predicting the weather was an art by itself in the 18th century. A scientific approach to weather forecasting started in earnest from the early 18th century, but progress was slow. So how did people like Jane Austen forecast the weather?

In the 18th century, people relied on observations, almanacs, and ‘indicator journals’ to predict the weather . Moon, clouds and wind, but also certain animal behavior provided important clues. Here are some examples from almanacs:

How to tell it will be raining soon

- If there appear a Circle about the Moon, you may expect stormy Weather to follow shortly after.

- If a Rainbow appear in the Morning, it is a Sign, for the most Part, of several Showers of Rain before Night.

- When the Wind keeps varying much, from one Quarter to another, you may expect Rain in twenty-four Hours.”

- If there be no Dew in a still Summer’s Morning you may expect Rain before Night, sometimes before Noon.”

- If the Smoke from the Chimnies, instead of ascending, fall to the Ground; you may expect Rain within twenty-four Hours, frequently sooner.

Animal behavior as indicator of rain

- The Crows flocking together in large Flights, holding their Heads upward as they fly, and crying louder than usual, is a Sign of Rain, as is also their stalking by Rivers and Ponds, and sprinkling themselves.

- When Sheep leap mightily, and push at one another with their heads [it indicates rain.]

- When Cats rub their Heads with their Forepaws (especially that Part of their Heads above their Ears) and lick their Bodies with their Tongues [it indicates rain.]

Indicators for sunny weather

- If the Clouds appear of a scarlet Red at or near the Setting of the Sun, it is a sure Sign of fair Weather

- In a hazy Summer’s Morning, when you see many Spider-webs upon the Grass, Trees, &c. you may expect it will clear up, and be hot, in general, before twelve o’clock.

- I have observ’d that many (dandelions), if not most of ’em do expand their Flowers and Down in Warm Sun-shiny Weather, and again close them towards Evening, or in Rain, especially at the Beginning of Flowering, when the Seed is young and tender.

How to tell it will be snowing soon

- If the Mist [in the mornings] continues many Days, as it frequently does in November and December, I think it is a sure Sign of much Rain or Snow falling in the Winter.

- Clouds like Woolly Fleeces appearing high and moving heavily; the Middle a Darkish Pale, and the Edges White, carry Snow in them

Scientific beginnings of meteorology in England

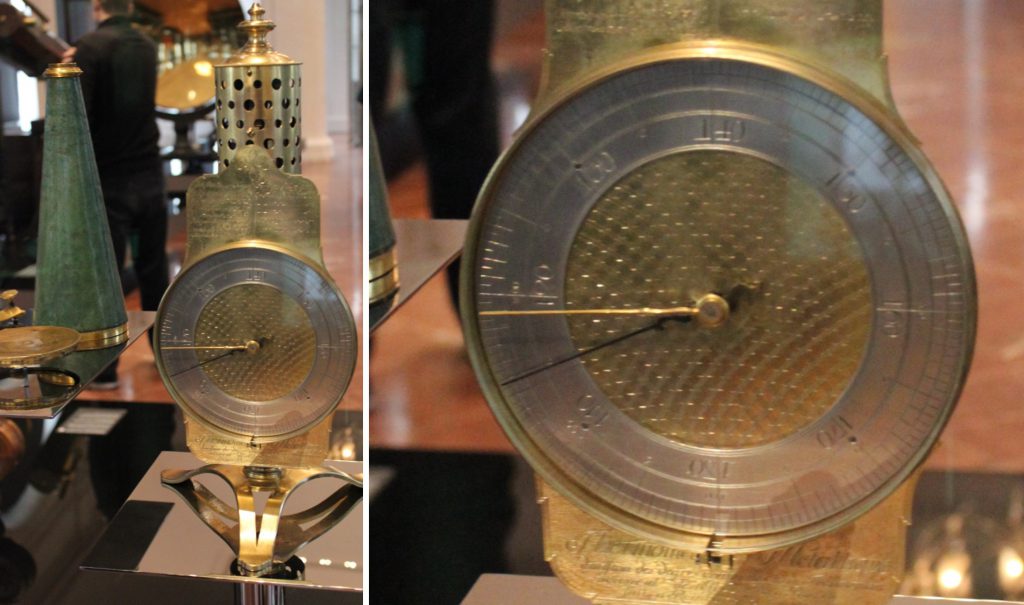

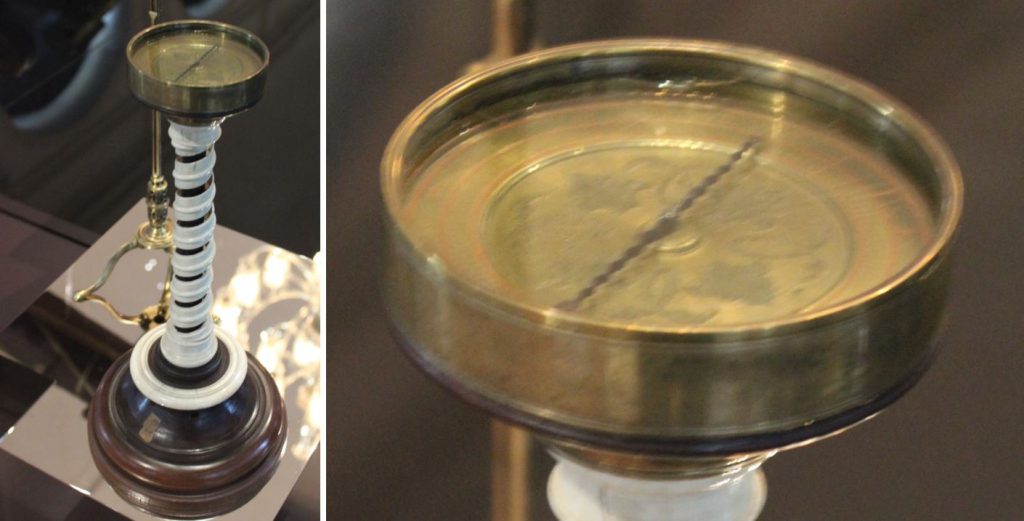

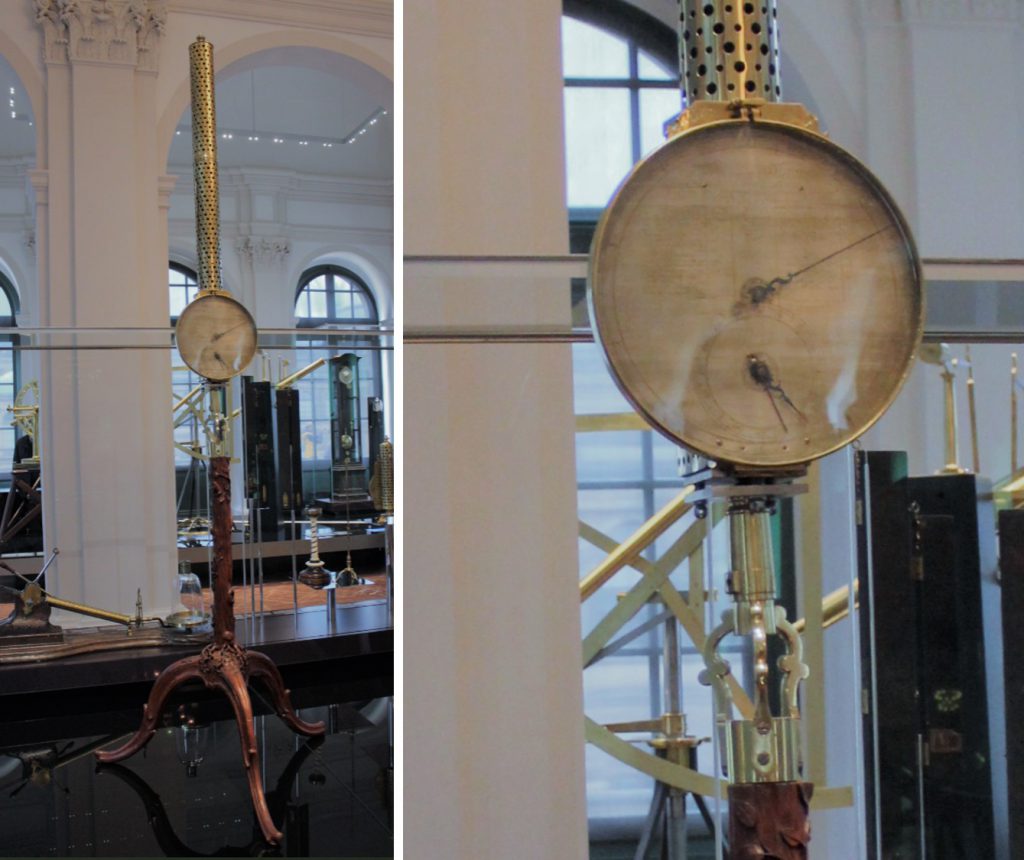

The scientific study of meteorology had its breakthrough when measuring instruments became available in the mid-17th century. By the early 18th century as many as 35 different temperature scales had been devised. Among them was the one of Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit. He produced accurate mercury thermometers calibrated to a standard scale that ranged from 32° – 96° (i.e. from the melting point of ice to body temperature).

Notable achievements by chemists and physicists helped to further develop meteorological research: The laws of gas pressure, temperature, and density had been discovered by Robert Boyle (1627 –1691), John Dalton (1766 –1844) wrote about the law of partial pressures of mixed gases, and Joseph Black (1728 –1799) contributed the doctrine of heat release by condensation or freezing (“latent heat”). These research results made it possible to measure and better understand aspects of the atmosphere and its behavior.

With regards to data recording, the meteorological observations by clergyman William Derham (1657 –1735) are among the earliest in England. James Jurin, the secretary of the Royal Society, laid out a plan for daily recordings of barometer and thermometer readings, wind strength and direction, precipitation and state of the sky in 1723. The English network of weather stations could count on fifteen international observers, ranging from Bengal and St. Petersburg to Massachusetts. But by the 1740s these early initiatives by individuals had dwindled away. One of the reasons was that the observations made were not comparable, as the correspondents of the network did not specify the exact nature of the instruments, location, or altitude. Additionally, researchers were not yet able to predict weather from patterns in the collected data.

The golden decade of weather observation – but where’s England?

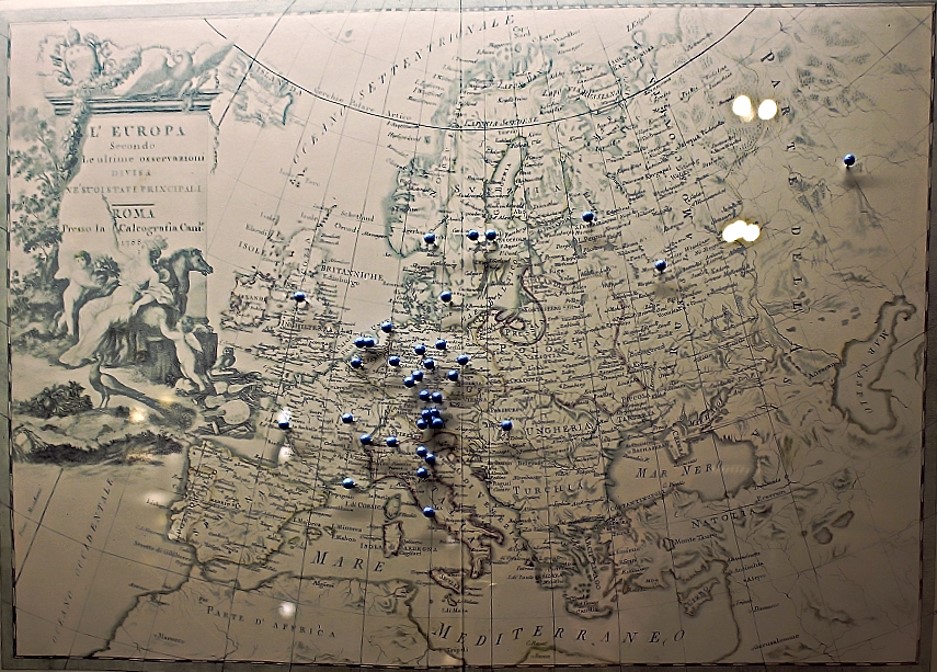

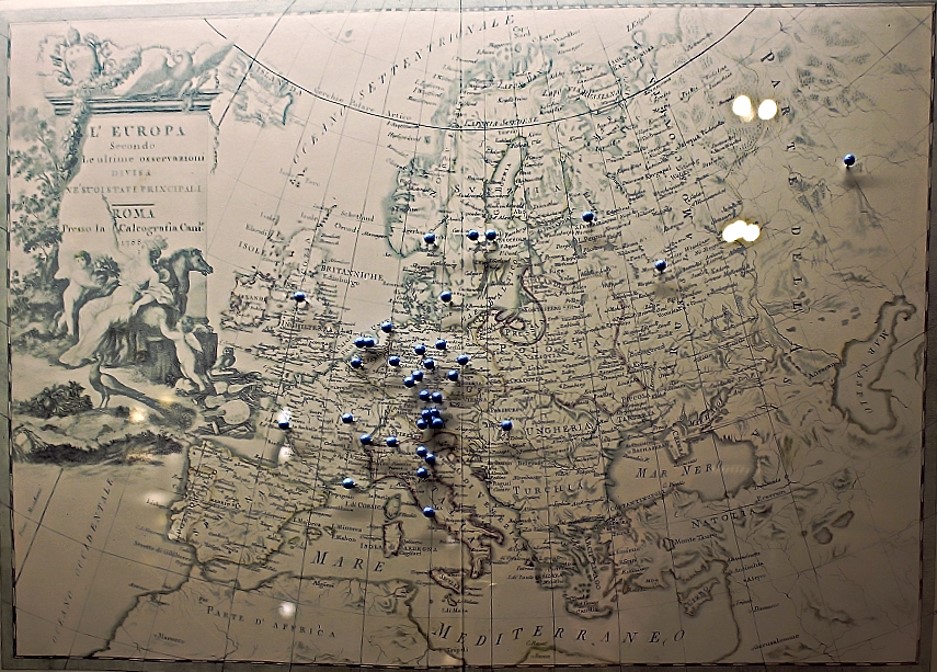

The Meteorological Society of Mannheim (Societas Meteorologica Palatina), was founded in 1781 to coordinate observations of the weather on an international scale.

The Meteorological Society invited 27 foreign locations to participate, including every station in the British Isles. The Royal Society of London also received an invitation, but it declined. Joseph Banks, the president of the society, claimed that he could find no one to do the observations.

A network of 39 stations recorded temperature, pressure and humidity, and various atmospheric phenomena such as the aurora borealis three times a day. Identical instruments were distributed to each station along with detailed instructions to ensure compatible sets of data. The so called “Mannheim times” for measurement – 7 am, 2 pm, and 9 pm – are still standard.

With the death of the society’s founders, wars and upheavals came financial constraints which impeded regular recordings. The number of participating stations decreased. The society was dissolved with its final publication in 1795. The wealth of weather data it provided is the base of our knowledge of the climate of the late 18th century.

The Meteorological Society of London

There was no meteorological organisation in England until in 1823 the Meteorological Society of London was founded. The inaugural meeting was held in a coffee house, Ludgate Hill, on the third Wednesday in October 1823 with “gentlemen attached to the science”. The Meteorological Society of London published its first map in 1840 – characteristically it was a map of rainfall in England.

Sources

- Stephanie Ann: Predicting the Weather 18th Century Style; www.worldturndupsidedown.com, May 26, 2012

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica: The Thermometer; www.britannica.com

- Per Pippin Aspaas / Truls Lynne Hansen: The Role of the Societas MeteorologicaPalatina (1781-1792) in the History of Auroral Research; Acta Borealia; A Nordic Journal of Circumpolar Societies, Volume 29, 2012 – Issue 2: The History of Research into the Aurora Borealis, 2012

- David C. Cassidy: Meteorology in Mannheim: The Palatine Meteorological Society, 1780-1795, Boston University, US

- James Rodger Fleming: Historical Perspectives on Climate Change; Oxford University Press, 2005

- Peter R. Cockrell: The Meteorological Society of London 1823 – 1873; Royal Meteorological Society

Photos were taken at Deutsches Museum in Munich and Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon (Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) in Dresden, Germany.

Related articles

The Girl, the Kite and the Eccentric Inventor

When weighing became ultimately fashionable – for men

The Reichenbach Case – Industrial Espionage at Boulton & Watt

The Poor Man’s Son Who Usurped the British Market of Optical Lenses

Object of Interest: Coach Clocks

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)