On 25th September 1799, shortly before 5 o’clock in the morning, the Wickhams woke up by the sound of guns. Were the French marching against Zurich again? William Wickham (1761 – 1840), England’s leading spy on the Continent, placed his wife Eleonore (1763-1836) under the care of his private secretary, the Count of St. George. He himself rode out reconnoitring the situation.

On 25th September 1799, shortly before 5 o’clock in the morning, the Wickhams woke up by the sound of guns. Were the French marching against Zurich again? William Wickham (1761 – 1840), England’s leading spy on the Continent, placed his wife Eleonore (1763-1836) under the care of his private secretary, the Count of St. George. He himself rode out reconnoitring the situation.

Serving the Crown in Switzerland

Since June 1799, William was serving Lord Grenville, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, as envoy to the Swiss and commissary general to the allied armies of Austria and Russia.

Only one year ago Switzerland had become the Helvetic Republic, but the political situation was far from stable: Even though France had encouraged the republican uprising in the Swiss cantons, and the French Revolutionary Army had invaded the country at the invitation of the Republican faction, Switzerland was a battle-zone between the French, Austrian, and Imperial Russian armies. The locals supported mainly the latter two. Zurich had been under the control of the allied armies since June 1799 when General Masséna’s troops were driven out of town. But Masséna had only consolidated to a defensive line in the north – and now he was back.

When William returned to Zurich later that day, he found Eleonore still at home, fast asleep in her bed, but fully dressed, and everything ready for an immediate departure if real danger should occur. So far, no alarm had been raised, and Eleonore a well as St. George believed the attack of the French to be a false one. But William knew real danger was ahead, and disorder would break out soon. There was no time to lose.

Captured by the French?

William was one of the persons most wanted by the French. And with their army approaching to Zurich on 25. September 1799, the Wickhams had only one option: Fleeing to Winterthur. They took care of a wounded acquaintance, had to leave William’ s calèche behind and off they went – separately. The flight was dangerous, as French hussars and chasseurs were skirmishing with retreating dragoons along the Winterthur road. The Wickhams luckily passed through.

Zurich was soon taken by the French. William’s calèche that the Wickhams had left behind was captured by them. The French press falsely boasted that they also captured Eleonore. But by the time this fake news was published in Paris, Eleonore had already safely arrived in Swabia.

A Life of Risk

Eleonore was no stranger to risks. She previously had to flee Zurich in a travelling carriage. Making her way had been difficult then, too, with people in panic and baggage-waggons in the streets. She had just managed to escape.

By September 1799, Eleonore had been married to William Wickham for more than 12 years, and they had one child. Their marriage was a happy one, a true partnership, with Eleonore being a moral and emotional support to William. They had met in Geneva, Switzerland, where Eleonore had been born as the daughter of a professor of mathematics in 1763, and William Wickham had studied from 1786.

William had begun to undertake secret work for the Government from 1793. Eleonore had been with William on several dangerous missions on the Continent. Additionally, when residing in London, letters of highest importance were sent to Eleonore’s address, directed to her maiden name. She also had a final word in the missions William was sent to: Foreign Secretary Grenville used to ask Eleonore for William’s availably before contacting William himself.

As the wife of a master spy, Eleonore had to cope with

- Extensive travelling: Eleonore travelled in Switzerland, England, France, Germany and Ireland. She lived, among others, in Zurich, London, Munich and Dublin.

- Being close to the action: At the time of battles, she was comparatively close to the action, though usually staying safely behind the army. Her task was to assist in quick communication.

- Dealing with information about assassination plots: According to a report by Sir James Craufurd, William had been the object of an assassination plan at least once. In 1789, a group of French emigres in London was believed to plot his murder. However, the plan was never carried out.

- Caring for a husband whose heath became frail from stress and overwork.

- Getting along with the staff: now and then, Grenville sent William new aides to assist him in his many tasks. One of them was Charles William Flint, then just 18, later a master spy himself. His first task was to escort Eleonore and a considerable sum of money from England to Switzerland in 1795.

Eleonore Wickham died in 1836. It is said that William never fully recovered from this loss.

Related articles

- Your Challenge: Equip the Army with Small-Arms between 1793 and 1815

- Writer’s Travel Guide: The Jersey Connection

- Burn after Reading: Spying Secrets of the Regency Period – Guest Post by Sue Wilkes

- What Would Have Been Your Role at the Congress of Vienna 1814/1815?

- Jane Austen, the Captain and the Smugglers of a Tiny Island

- The Lady is A Spy: Joanne Major and Sarah Murden Uncover the Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs

- Attractive, Distinctive, One Size: The Military Uniform in the Late 18th Century

Sources

- The correspondence of the Right Hon. William Wickham from the year 1794. Ed., with notes, by W. Wickham, Volume II, published in 1870. https://archive.org/details/correspondencew01wickgoog

- Durey, Michael: William Wickham, Master Spy: The Secret War Against the French Revolution; Routledge, 2009.

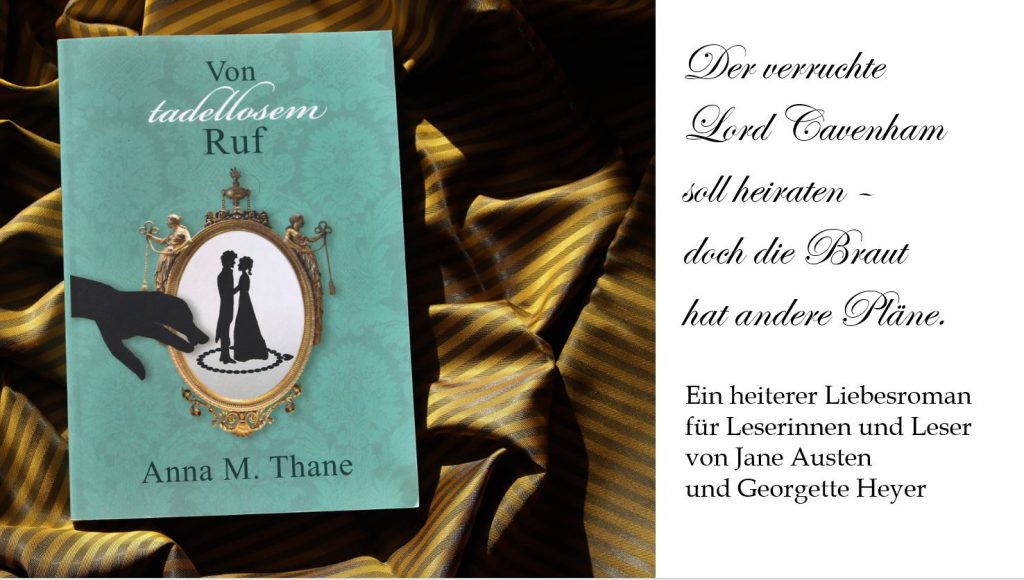

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)