- How to get to Milan in the 18th century

- Where to stay

- Dangers and annoyances

- Napoleonic sight-seeing in Milan

Travelling to Italy had always strongly appealed to the British aristocracy. Milan had been a favourite since Maria Theresia, sovereign of the Holy Roman Empire, remodelled the city in the second half of the 18th century: Milan featured lovely public gardens, and the fabulous opera house La Scala. But Alas!, visiting this splendid city came to a halt for British travellers from 1796 to 1814, when Napoleon had occupied Milan and most parts of Northern Italy. It was only after the Battle of Waterloo that British tourists could visit Milan again. One of the most famous tourists was Lord Byron, who spent two weeks in Milan in October 1816.

Lord Byron had always been an admirer of Napoleon. In Milan, he was lucky to get acquainted with the French essayist Stendhal (Henri Beyle by real name). Stendal had worked under Napoleon’s Secretary of State. Byron and Stendal met almost every evening for several weeks, and Byron questioned Stendal about his hero.

Some British tourists took a special interest in seeing the places of Napoleon’s power. Thus, locations connected with Napoleon became a curiosity for tourists. I have selected some of them for you in this post. Find out more about Napoleonic Milan:

How to get to Milan in the 18th century

British travellers to Milan usually go there via Calais, Paris, and Switzerland. The journey through Switzerland becomes easier after the war, as Napoleon had built a military road from 1801 to 1805. Thus the recommended route through Switzerland is via Visp, Brig, and Simplon.

Population and climate

Milan has about 130.000 inhabitants in the 18th century.

The winters are cold, the summers very hot. Autumn and spring are considered damp and unwholesome. Travel-writers warn that the irrigation of the rice-fields around Milan renders the air insalubrious.

Where to stay

British travellers frequent selected hotels such as Albergo Reale, Albergo della Gran-Betragna, Croce di Malta, I Tre Re and Il Pozzo.

When Byron arrived in Milan in 1816, he had rooms at L’ancien Hotel de San Marco, but found them dirty and unpleasant.

Dangers and annoyances

Footpads

Milan at night tends to be dangerous, as many footpads lurk in the dark streets. Prudent travellers always take a carriage after dark.

Unrests

After Napoleon’s abdication on 20th April 1814, there were protests and revolts in the streets let by nobles hostile to the Austrian regime.

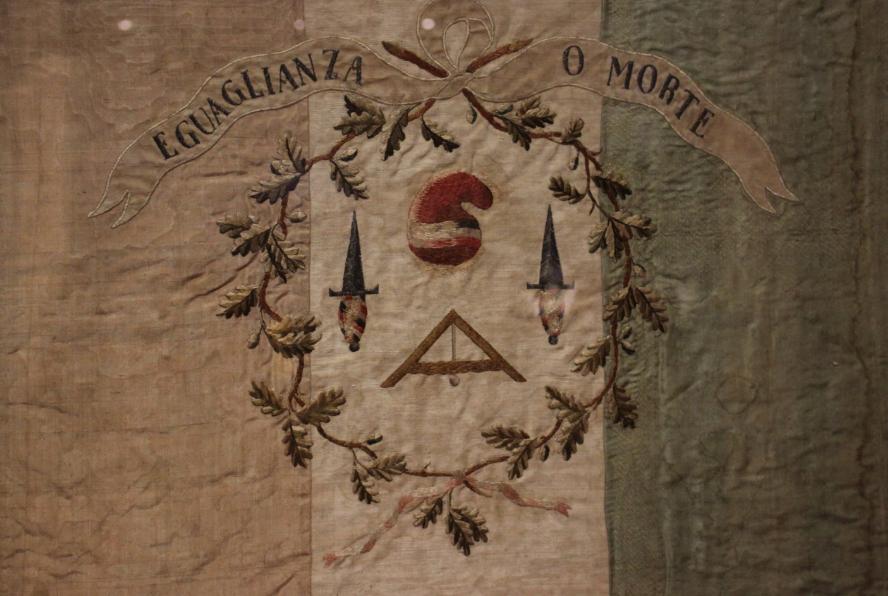

After the end of Napoleon’s reign, the Austrians are again the sovereigns of Milan. A large number of people from all classes, dreaming of an independent Italy, are unhappy with this political situation. They secretly meet and conspire against the Austrian reign.

Around 1819, Lord Byron, travelling again in Northern Italy, was in contact with conspirators of the carbonari, a group fighting for an independent and unified Italy.

Travellers should be aware that the Austrians monitor suspicious groups carefully and are ready to make arrests.

From the 1820ies, political unrests occur in Milan.

Things to see and do

- A trip to Milan inevitably includes a visit to the opera La Scala, considered the best opera in the world. Popular theatres also are Il Theatro Re, the Canobiana and the Carcano.

- Tourists always enjoy promenading and watching the locals. The principal promenades in Milan are the Ramparts, the Corso and the Esplande.

- The Biblioteca Ambrosiana is the Mecca of those dedicated to the arts. The historic library from the early 17th century also houses the Ambrosian art gallery. Lord Byron visited the library in October 1816. He was especially interested the love letters exchanged between Lucrezia Borgia and Pietro Bembo and Byron allegedly stole a lock of Lucrezia Borgia’s hair that was on display.

- Of the many churches, Milan Cathedral was the most important to visit. As today, it was possible in the 18th century to go to the top of the building. Gentlemen and ladies would have to climb 468 steps to admire the fretwork, carving and sculptures.

Napoleonic sight-seeing in Milan

Milan Cathedral

For British tourists interested in visiting the places of Napoleon’s power the cathedral of Milan is a must-see, as he had crowned himself King of Italy at the cathedral on 26. May 1805.

For British tourists interested in visiting the places of Napoleon’s power the cathedral of Milan is a must-see, as he had crowned himself King of Italy at the cathedral on 26. May 1805.

When Napoleon arrived in Milan, the cathedral was an unfinished building. Actually, it had remained incomplete ever since its consecration in 1418. Napoleon ordered to finish the cathedral as a gift to the city. He assigned the architect Carlo Pellicani to complete the façade. As a gift of Milan to its new French ruler, a statue of Napoleon was placed at the top of one of the spires.

When Napoleon crowned himself King of Italy in 1805 the building was still under construction. Nevertheless the site was well-chosen: The cathedral of Milan was the place where the sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire had been crowned for centuries. Napoleon legitimised his reign by following this tradition. He also made sure to include as much of the traditional ceremony as possible.

As all sovereigns had worn the Iron Crown of Lombardy for their coronation, Napoleon had it brought to Milan from Monza. However, he also had a crown made for himself (see photo below) as well. During the ceremony, on taking up the Iron Crown, Napoleon uttered the traditional formula: ‘God has given it to me; woe to those who will touch it‘.

Here are some photos from Napoleon’s coronation equipment:

Napoleon’s own crown for his coronation as King of Italy

Napoleon’s own crown for his coronation as King of Italy

The Royal Palace

The Royal Palace was built in the 1790ies. It was bequeathed to Napoleon by the Italian Republic in 1802. The gardens were the first in Milan to be designed in the English style.

After his coronation as King of Italy, Napoleon soon handed Milan over to his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais (1781 – 1824). Eugène moved into the beautiful Royal Palace.

You can still enjoy the splendour of the place today, as it houses the Civic Modern Art Gallery.

Palazzo Serbelloni

Napoleon and Josephine stayed at the Palazzo Serbelloni for three month in 1796. The palazzo can be visited by appointment.

The Napoleonic era in Milan in photos

Napoleon presented the tricolour flag to the Lombards who fought in the French army in Milan in October 1796.

Napoleon presented the tricolour flag to the Lombards who fought in the French army in Milan in October 1796.

Arrival of the French army in Milan. It enters the city through the Porta Romana. On the right of the gate, the Milanese had erected the so called Liberty tree as a symbol of the democratic rebirth of the people.

Arrival of the French army in Milan. It enters the city through the Porta Romana. On the right of the gate, the Milanese had erected the so called Liberty tree as a symbol of the democratic rebirth of the people.

Uniform of the National Guard of Milan, founded in 1796

Uniform of the National Guard of Milan, founded in 1796

Related posts

Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 1)

Gossip Guide to the Kingdom of Naples: Inside the Palace of Caserta

Writer’s Travel Guide: The British and the Grand Tour to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily (Part 2)

Writer’s Travel Guide: The Jersey Connection

Find all Writer’s Travel Guides here

Thanks

Special thanks to Ann Pearson for advise about Stendal.

Sources

Starke, Marianna: Travels on the Continent: Written for the Use and Particular Information of Travellers; London, 1820

Museo del Risorgimento, Via Borgonuovo, 23, 20121 Milano, Italy; http://www.museodelrisorgimento.mi.it/

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)