Being a child in the Regency period was often hard. Even treats could be dangerous. Sugar plums, comfits, and sweetmeats from the street vendor’s tray were frequently made with poisonous colourants. Society appeared to care little. Fortunately, one man took up the fight for food safety: Frederick Accum, a pioneering chemist who became the first “food detective”.

“Take a Bit of Verdigris…”

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, confectioners, sugar-bakers, and cooks became increasingly enthusiastic about adding colourants to their products. Cookbooks of the time offered recipes containing poisonous chemicals to unsuspecting household cooks. One such recipe, “To Make Greening” in Modern Cookery, indeed began with the alarming instruction: “Take a bit of verdigris…” — verdigris being a copper salt and highly toxic.

Comfits — sugar-coated seeds and spices — were often coloured red with a blend of vermilion and red lead, producing a bright orange-red hue irresistible to children. Vermilion was manufactured for painters’ palettes, not the kitchen. When “enhanced” with red lead, the result was not only more vivid but also far more poisonous.

Other sweetmeats fared little better. Some were dyed with copper-based preparations to achieve striking greens, while copper compounds were also used to preserve fruits such as limes, citrons, and plums. Imported dried fruits, too, were frequently impregnated with copper to improve their appearance.

Thus, the colourful confections of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries probably contained at least one of the following: red lead (lead(II,IV) oxide), vermilion (mercury(II) sulphide), verdigris (copper acetate), blue vitriol (copper(II) sulphate), sugar of lead (lead(II) acetate), white lead (lead(II) carbonate), or Scheele’s Green (copper(II) arsenite).

Beware the Copper Pan!

Even conscientious confectioners, sugar-bakers, and pastry-cooks were not entirely safe from unwittingly poisoning their customers. The danger often lay in their equipment. If their copper pans, moulds, and vessels were not properly tinned, cleaned, and inspected, verdigris could easily form on the surface.

A single accidental dose was unlikely to be fatal, but repeated ingestion — even in minute quantities — could induce vomiting, jaundice, coma, and a host of other gastrointestinal ailments.

Enter the “Food Detective“

Frederick Accum (1769–1838) was a Consultant Chemical Analyst and lecturer based in London. In 1820, he published his landmark work, A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, in which he exposed the scandalous and often criminal adulteration of food. He was the first to describe the harmful effects of foods containing poisonous colourants and was a pioneer in applying chemistry to the protection of public health. He frequently appeared as an expert witness in court.

His book, A Treatise on Adulterations, reached a wide audience: the initial print run of 1,000 copies sold out within a month.

Self-Help for the Discerning Consumer

Being a practical man, Accum also provided readers with a little do-it-yourself chemistry for detecting toxic metals in food. In A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, he wrote:

“The presence of copper may be detected by pouring over the comfits liquid ammonia, which speedily acquires a blue colour if this metal be present. The presence of lead is rendered obvious by water impregnated with sulphuretted hydrogen, acidulated with muriatic acid, which assumes a dark brown or black colour if lead be present.”

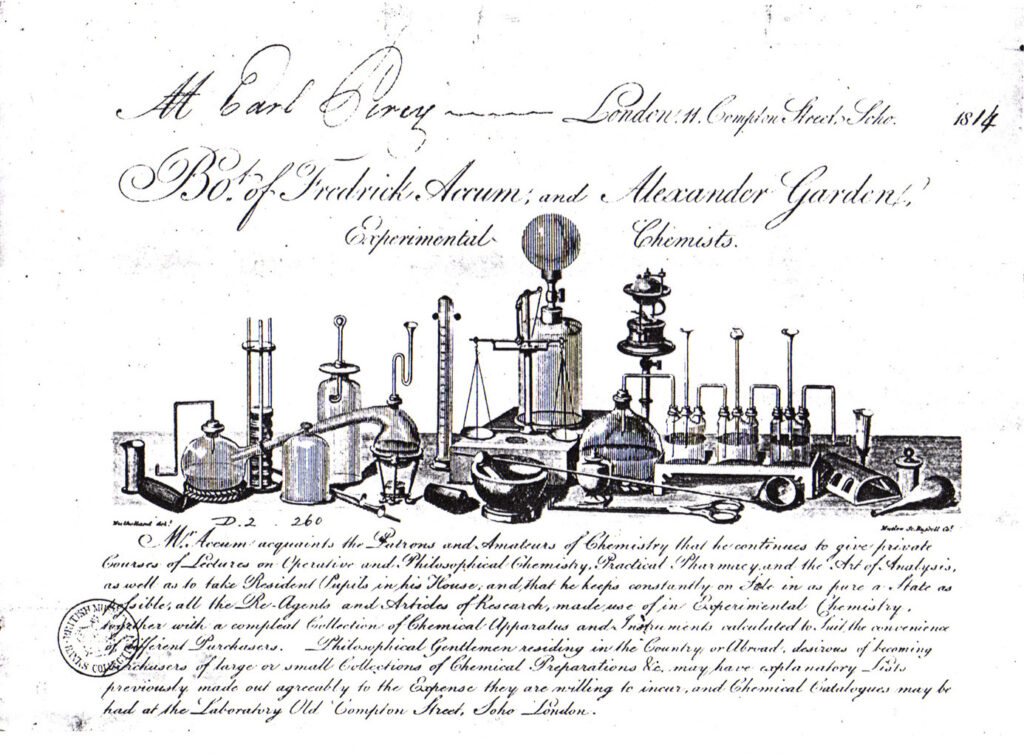

Naturally, the necessary reagents and apparatus could be purchased — conveniently enough — from Mr Accum’s own shop in London.

Although Accum did not live to see the introduction of modern food safety legislation, his pioneering work inspired others to continue the struggle. In the 1850s, Thomas Wakley established the Analytical Sanitary Commission to investigate food adulteration, and in 1875 Britain finally enacted the Sale of Food and Drugs Act.

How to Become a Consultant Chemical Analyst in the Regency period

Frederick Accum might well be described as the Sherlock Holmes of chemistry. Born in a small town in northern Germany, the son of a soap-boiler, he received a sound education and was apprenticed to a leading pharmacist with establishments in both Germany and England. His passion for learning and his strong interest in chemistry soon set him apart.

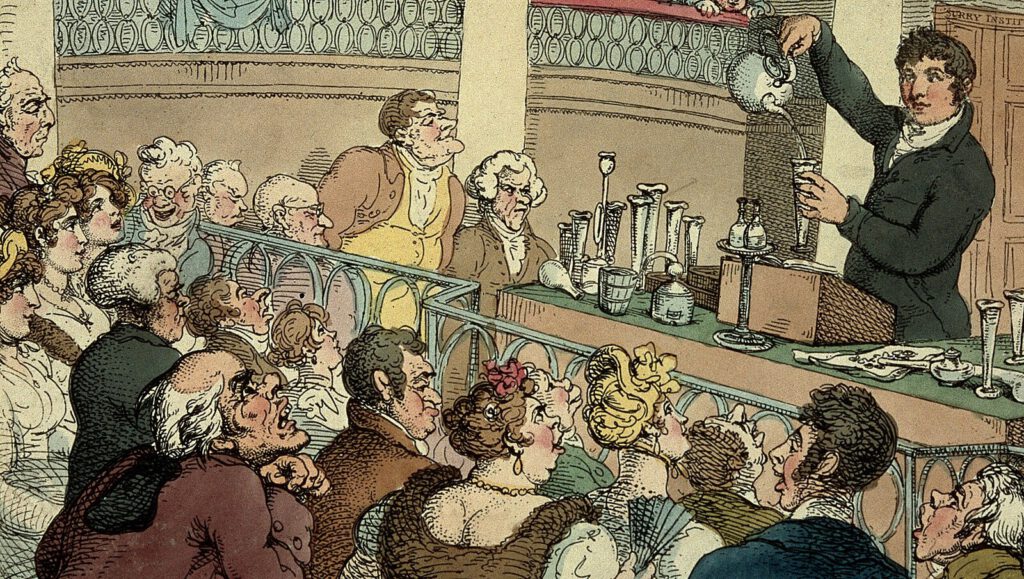

In 1793, Accum seized the opportunity to work as an assistant chemist in the London branch of the pharmacy. There he pursued studies in science and medicine, became active in the city’s scientific circles, and established connections with influential figures. With the support of Count Rumford, Accum became Assistant Chemical Operator at the Royal Institution, working under Humphry Davy for several years. He later moved on to lecture at the Surrey Institution. In 1803, he published his first book, System of Theoretical and Practical Chemistry.

Accum was indefatigable. He set-up his own shop, gave private lectures from his own home, and wrote numerous chemical papers. As Consultant Chemical Analyst, he appeared as an expert witness in court. When he published A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, he stood at the height of his career.

It is unfortunate that his professional life was marred by scandal only a little later — he was accused of damaging books at the Royal Institution Library — an incident that forced him to flee back to Germany.

Related articles

Sources

- Accum, Frederick: A treatise on adulterations of food, and culinary poisons; London: Longman, 1820

- Antony D. Dayan, Joshua D Dayan: Accum and food adulteration: A forgotten bicentennial, Toxicology Research and Application 2021-01 | Journal article, DOI: 10.1177/23978473211033034

- Caroll Pohl-Ferry, Caroll Pohl-Ferry: eath in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 2, Chemistry views, October 1, 2024 (ChemistryViews.org)

- Harold T. McKone: The Unadulterated History of Food Dyes, in: ChemMatters, December 1999

- William Palmer: Frederick Accum (1769-1838) and the application of chemistry to social problems 2015, New developments in science education research (edited Nathan Yates). New York: Nova Science Publications, pp. 97-106.

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)