Coffee was a popular hot beverage in 18th century Britain. Coffee houses spread across cities, and grocers sold both coffee beans and ground coffee to private consumers. As demand rose, coffee became the subject of fraudulent practices. How could customers be protected from adulterated products? And what other crimes were related to coffee?

How to Make Spurious Coffee

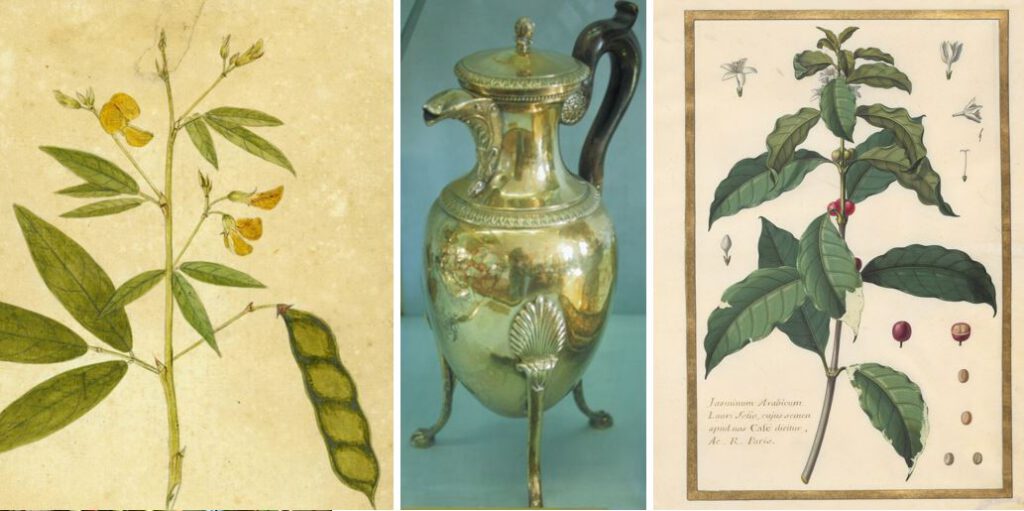

Ruthless coffee dealers and grocers counterfeited coffee powder by using pigeon beans and peas in place of coffee beans. Some even mixed sand and gravel into the powder or added sweepings of coffee to make it appear genuine. This concoction would easily deceive an unsuspecting customer.

The Crown Against Fraudulent Coffee Dealers

Outraged by the fraud, Parliament passed laws in 1718, 1724, and 1803.

The Coffee Act of 1718 imposed a penalty on those who fraudulently increased the weight of the coffee they sold to unsuspecting customers. This increase in weight was achieved by using water, grease, or butter during or shortly after the roasting process. Naturally, this also made the coffee unwholesome. The penalty was £20 (approximately £4,000 in today’s money). It was increased to £100 by a subsequent Act in 1724.

The Coffee Act of 1803 detailed fraudulent actions more explicitly and made the possession of adulterated coffee illegal. It also allowed excise officers to seize adulterated products directly from shops or manufactories. The Act explicitly stated:

“… if after the first day of September 1803, any burnt, scorched, or roasted peas, beans, or other grain, or vegetable substance or substances prepared or manufactured for being in imitation of or in any respect to resemble coffee or cocoa, or alleged or pretend by the possessor or vendor thereof to be, shall be made or kept for sale, or shall be offered or exposed for sale or shall be found in the custody or possession of any dealer or dealers in or sellers of coffee, or if any burnt, scorched or roasted peas, beans or other grain, or vegetable substance or substances not being coffee, shall be called by the preparer, manufacturer , possessor or vendor thereof by the name of English or British coffee, or any other name of coffee (…) the same respectively shall be forfeited, together with the packages containing the same, and shall and may be seized by any officers or officers of Excise; and the person or persons preparing, manufacturing, or selling the same, or having the same in his, her, or their custody or possession, or the dealer or dealers in or seller or sellers of coffee or cocoa, in whose custody the same shall be found, shall forfeit and lose the sum of one hundred pounds.”

(Pigeon Pea, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany / 18th century cafetière / Handcoloured copperplate engraving by F. Sansom Jr. after an illustration by Sydenham Edwards from William Curtis’ Botanical Magazine, T. Curtis, London)

A Close-Up at Coffee Crimes during the Regency period

- In 1817, excise officer J. Richardson seized four sacks, five tubs, and nine pounds in paper of a powder made to resemble coffee at the workshop of John Malins, a coffee dealer. In reality, it contained only a small amount of coffee mixed in. The total adulterated powder weighed 1,567 pounds. Richardson also seized 279 pounds of whole roasted peas and beans, mixed with some grains of coffee. John Malins was tried in 1818. His servants testified against him: J. Laws and Thomas Jones both admitted to regularly roasting peas and beans and grinding them into powder to resemble coffee. They also testified that Malins sometimes mixed sweepings of coffee into the peas and beans. The adulterated mixture was then sold to grocers. Malins was fined £100.

- Excise officers Charles Henry Lord and John Pearson caught Mr. Chaloner with nine pounds of spurious coffee, which consisted of ground peas, beans, sand or gravel, and some coffee. He was fined £90.

- Mr. Fox was tried for selling fake coffee to the poor. He argued that he did so to help those who could not afford higher prices and never sold it as genuine coffee. He was fined £50.

- Grocer Alexander Brady admitted to selling fake coffee for twenty years. At his trial, his coffee was tested and found to be unfit for human consumption. He was fined £50.

Dark Coffee Crime: Coffee and Slavery

We often overlook the connection between coffee and a crime against humanity. Throughout the 18th century, coffee was grown on plantations in the Americas, where coffee beans were harvested under cruel conditions by enslaved people. Demand for coffee led to an enormous expansion of slave-based production in the French and Dutch colonies of the West Indies.

In the late 1720s, successive successful coffee harvests from West Indian slave plantations led to a significant decrease in prices. Coffee started to become affordable by a wider group of people. The West Indies became the centre of coffee production for Europe: Around 1755 already almost 80% of the European-consumed coffee was West Indian. By the 1760s, enslaved people in the French colony Saint-Domingue produced more than half of the world’s coffee. In 1787 alone, the French imported approximately 20,000 slaves from Africa to Saint-Domingue. The death rate from illnesses such as yellow fever was horrifying: at least 50% of the slaves died within a year of arriving from Africa.

When the slaves of Saint-Domingue emancipated during the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), it had a profound impact on coffee production. Over 1,000 plantations were destroyed, and Haiti’s coffee industry collapsed. With the enduring shortage of European coffee, and wars and blockades largely cutting off France and Holland from direct access to the coffee supplies of their colonies, locations of production and trade routes changed. Jamaican plantation became important for the coffee production, and Britain, North America and Hamburg played a significant role as traders. The British Continuance of Laws Act of 1803 even explicitly encouraged the growth of coffee in Britain’s ‘plantations in America’.

Related articles

Sources

Accum, Frederick: A treatise on adulterations of food, and culinary poisons; London: Longman, 1820

Combrink, Tamira: “Slave-based coffee in the eighteenth century and the role of the Dutch in global commodity chains”; Taylor & Francis Online, Published online: 28 Feb 2021 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0144039X.2020.1860465#d1e104 )

El-Beih, Yasmin: „How coffee forever changed Britain”; BBC, 19 November 2020 (https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20201119-how-coffee-forever-changed-britain)

Syrett, Victoria: “How coffee has shaped Britain’s maritime history”; Royal Museums Greenshich, Published 10 Oct 2023 (https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/library-archive/how-coffee-has-shaped-britains-maritime-history)

A history of coffee in Britain; at: DRWakefield, 31 December 2013 (https://drwakefield.com/news-and-views/a-history-of-coffee-in-britain/ )

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)