It’s 1814, and we find ourselves in a hidden cellar on a dark backstreet in the less noble parts of London. This is the domain of a ‘wine-brewer’, the artist among food forgers. ‘Wine-brewers’ possess many talents: they can give an immature red wine more astringency, render cloudy white wine transparent, and even conjure a Bordeaux from sloe berries. One might be tempted to admire their craft, were it not for the fact that some of their ingredients are unappetising, or even dangerous to the health and lives of unsuspecting consumers.

Let’s discover how our wine-brewer ‘doctors’ wine. Like most of his kind, he is willing to introduce novices like us to the art—for a considerable sum of money, of course. Here are some tricks of the trade:

- Add a portion of alum to a young and meagre red wine to brighten its colour.

- Use gypsum to render cloudy white wine transparent.

- Add Brazil wood, or the husks of elderberries or bilberries, to port to give it a deep, rich purple tint.

- Upcycle insipid wines to impart particular flavours, such as bitter almonds for a nutty taste.

- Add oak-wood sawdust to immature red wine to impart more astringency.

- To create the bouquet of a high-flavoured wine, add sweet-brier, orris-root, clary, cherry laurel water, or elderflowers.

If you are tempted to try your hand at it yourself, in 1814 you could buy most ingredients more or less legally from those dealers who do business with wine-brewers. Sawdust, for instance, is supplied by shipbuilders.

How to Counterfeit Champagne

Our wine-brewer then reveals the secret of making champagne—counterfeit champagne, of course:

“Take of white sugar, 8 pounds; the whitest brown sugar, 7 pounds, crystalline lemon acid or tartaric acid, 1 ounce and a quarter, pure water, 8 gallons, white grape wine, two quarts, or perry 4 quarts, of French brandy, 3 pints.

Put the sugar in the water, skimming it occasionally for two hours, then pour it into a tin and dissolve it in the acid; before it is cold, add some yeast and ferment. Put it into a clean cask und add the other ingredients. The cask is then to be well bunged, and kept in a cool place for two or three months; then keep it cool for a month longer, when it will e fit for use. If it should not be perfectly clear after standing in the cask for two or three month, it should be rendered so the use of isinglass.”

For pink champagne, we learn, simply add 1 lb of fresh or preserved strawberries, and two ounces of powdered cochineal.

Don’t Forget to Treat the Wine Bottle!

To make even experienced customers believe they are buying genuine quality wine, wine-brewers take care to make bottles and wooden casks look as though they have held mature wine for a long time. This special treatment is called crusting:

“Make a hot saturated solution super-tartrate of potash mixed with a decoction of Brazil-wood. Crystalize it and line the interior surface of the wine bottle with it. You can also use for wooded casks. Treat the whole interior with it. Don’t be afraid to show the treated wood casket to your customers: They will readily belief that the beautiful dark colour and fine crystalline crust are a sign of quality.”

A wine-brewer worth his salt will not forget to treat the cork as well: he simply colours the lower part of it with red paint, as if it had been in contact with wine for a long time.

Beware, There’s Poison!

While the techniques described above are deceptive, but harmless (even though one might not wish for isinglass in one’s champagne!), some wine-brewers use an ingredient that could make consumers sick, and even kill. It’s the highly poisonous lead, which prevents wine from becoming acidic.

Yet, irresponsible wine-brewers and wine merchants persuade themselves that a minute quantity of lead is harmless and will prevent wine from turning. Of course, wine adulterated with even the smallest quantity of lead becomes a slow poison.

The Enlightened Consumer Does the Wine Test!

Let’s leave the hidden cellar of the London backstreet. As a consumer of wine, how can one determine whether their wine contains the poisonous lead? Thanks to progress in science and chemistry, a relatively simple wine test can be applied:

“It consists of water saturated with sulphuretted hydrogen gas, acidulated with muriatic acid. By adding one part of it, to two of wine, or any other liquid ‘suspected to contain lead, a dark coloured or black precipitate will fall down, which does not disappear by an addition of muriatic acid; and this precipitate, dried and fused before the blowpipe on a piece of charcoal, yields a globule: of metallic lead.

The enlightened consumer obviously needs some understanding of chemistry, but acquiring this knowledge could save a life. It may also be enjoyable to detect extraneous colours in wine. For this, one would use either lime water or lead acetate (note: lead acetate causes lead poisoning):

- Lime water renders wine coloured with beetroot colourless.

- Acetate of lead renders wine coloured with bilberries, elderberries, or Campeche wood blue.

Related articles

Source

Accum, Frederick: A treatise on adulterations of food, and culinary poisons; London: Longman, 1820

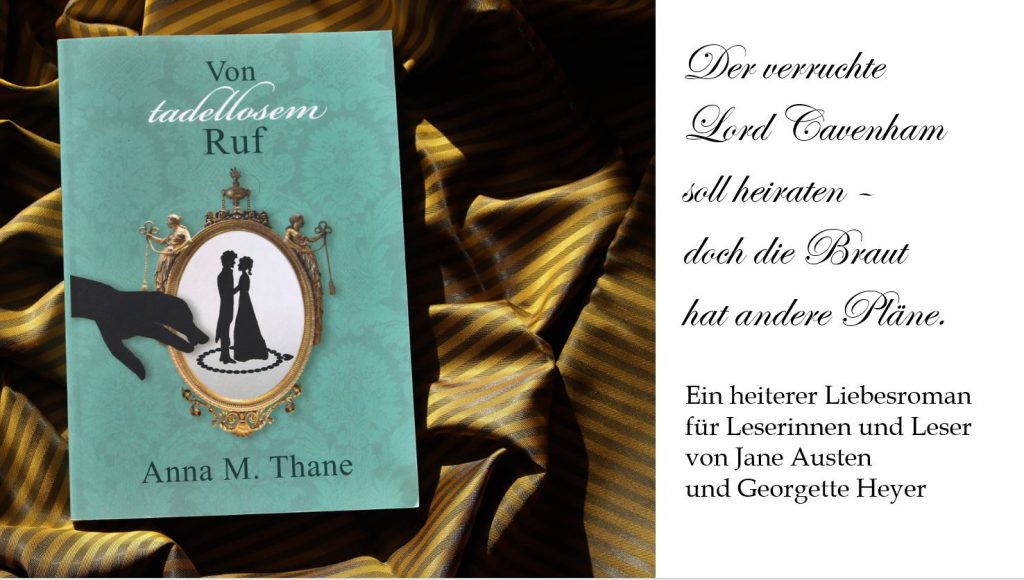

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)