With the scientific voyages of the mid-18th century, many previously unknown plants reached Britain and the Continent. Naturalists on these expeditions sent seeds to their sponsors, as well as to wealthy individuals. In Europe, botanists eagerly welcomed new seeds from Asia and America. They competed to describe them first, as this offered a chance to make a name for oneself in botany.

Many exotic flowers quickly became known within expert circles, and wealthy amateur gardeners competed in a friendly manner to be the first to successfully cultivate the new species. But how quickly did new species such as the zinnia come to the attention of the public, and make their way into the gardens of the middle classes? Would, for example, Jane Austen have known the zinnia, which reached Britain in 1753? Let’s find out more.

The zinnia’s journey from America’s equatorial countries a to British gardens begins around 1736. Thirty-three-year-old Joseph de Jussieu, naturalist and physician, arrived in Peru as a member of the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator. The expedition was led by five French and Spanish mathematicians and astronomers. While they carried out arc measurements to determine the radius and circumference of the Earth, Joseph de Jussieu’s task was to collect plants – about 400 specimens are attributed to him. Though most of his descriptions were lost, it is very likely that he sent seeds of Zinnia peruviana to Paris in the 1740s. From there, it was distributed to botanical gardens and the glasshouses of amateur naturalists.

Scientific sensibilities: naming a tall and lanky plant from Peru

The plant Joseph de Jussieu collected in Peru wasn’t called “zinnia” at the time. In the world of botany, the race to name it began with the arrival of the seeds. The competition included some of the most distinguished naturalists of the time:

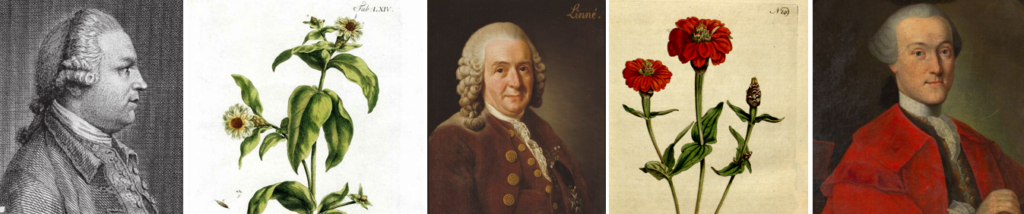

- The first person to describe the plant scientifically was the father of taxonomy himself, Carl von Linné. It is believed that he received some of the seeds Joseph de Jussieu had collected, or saw the plant when visiting the de Jussieu family. In 1753, he named the plant Chrysogonum peruvianum, placing it within the Asteraceae family.

- Anatomist and botanist Johann Gottfried Zinn, director of the famous botanical garden in Göttingen, also received seeds from Peru via Paris. In 1757, he described the plant as a rudbeckia (in full a long-winding, Rudbeckia foliis oppositis hirsutis ovato-acutis, calyce imbricatus, radii petalis pistillatis). The award name – “Rudbeckia with opposite, hairy, ovate-acute leaves, imbricated calyx, pistillate petal rays” – made fellow botanists giggle behind Zinn’s back and nettled the sensibilities of Carl von Linné.

- Carl von Linné reviewed Zinn’s work in 1759 and felt obliged to take up his quill. He reclassified the plant as Zinnia peruviana. He chose “Zinnia” in honour of Zinn – perhaps because Zinn had correctly identified it as belonging to the Asteraceae family. He also pointed out that he had already described the flower in 1753. The rules of botanical nomenclature are simple: the person who describes a plant first has the right to name it. Thus, we know the plant as Zinnia peruviana today.

- In Britain, plant expert Philip Miller of the Chelsea Physic Garden classified the plant as Bidens calyce oblongo squamoso (“Bidens with an oblong, scaly calyx“) in his book Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in The gardeners dictionary, exhibited on three hundred copper plates” (published in 1760).

Miller wrote: “The seeds of this plant were sent from Peru to the Royal Garden at Paris, where it has flourished a few years past, and the plants have produced seeds there, which have been communicated to several curious gardens in Europe. The seeds were sent me in the year 1753; and the following summer the plants flowered, and produced good seeds in the Chelsea Garden.”

The British didn’t care much about the fact that Carl von Linné had named the plant a zinnia. The plant was only widely recognised as a member of the Zinnia genus from 1769 onwards.

From scientist’s glasshouses to the art world

Zinnias grow easily in warm and sunny climates. However, the British climate was not entirely to their liking. Garden manuals of the late 18th century advised gardeners to raise them in a hot-bed before transferring them to the open garden. Zinnias required care but nevertheless made their way out of the glasshouses of amateur botanists and into the hands of a wider group of keen gardeners.

By 1776, the red Zinnia pauciflora and yellow Zinnia multiflora appeared in nursery catalogues, such as The Gentleman and Lady’s Gardener by seedsman Robert Edmeades of Fish Street Hill, London. Zinnias are also mentioned in Every Man His Own Gardener by Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie, published in 1782. Of course, the most famous plant nursery in Britain, Lee of Hammersmith, sold the plant too.

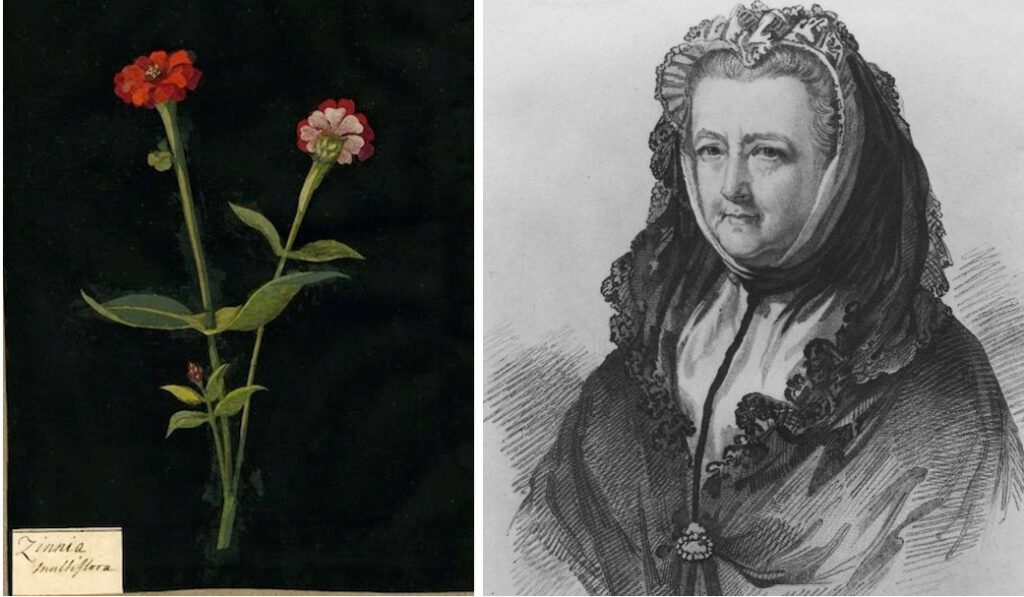

From the late 1770s, zinnias became subjects of art. Mary Delany, an artist and Bluestocking well-connected in aristocratic circles, created the work Zinnia Multiflora using tissue paper and hand colouring in 1779 for her Flora Delanica, a series of 985 flower specimens. Queen Charlotte took a strong personal interest in Delany’s skills and had her work sent to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

You will notice that by this point names such as Zinnia pauciflora and Zinnia multiflora were in use. Scientifically speaking, these were still Zinnia peruviana, as The Botanical Magazine by William Curtis correctly noted in 1792.

Zinnias all over: more varieties flower in British gardens

New seeds for zinnia enthusiasts arrived from New Spain. Members of the Spanish Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain (1787–1803) sent thousands of seeds and plants to Madrid and to collectors in Britain.

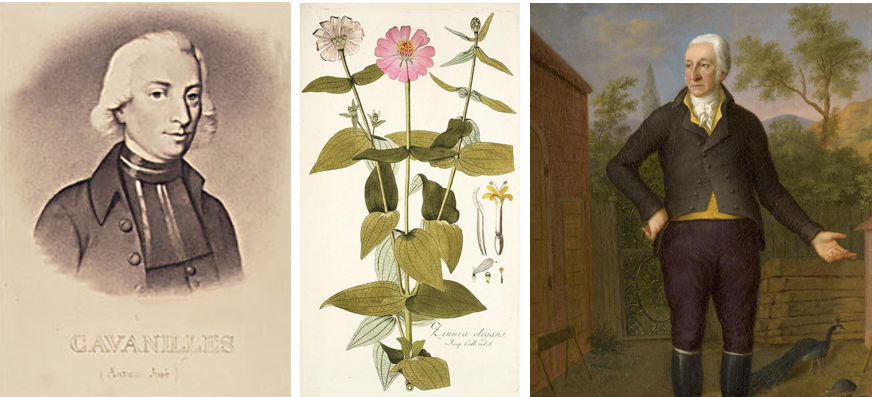

Once again, botanists competed to name the new variety of zinnia. It was Nikolaus Joseph Jacquin, professor of botany and chemistry at the University of Vienna, who gained botanical fame in 1793 by correctly describing the purple-coloured Zinnia elegans. Honourable mention goes to Antonio José Cavanilles, director of the Royal Gardens in Madrid, who described the plant as Zinnia violacea in 1792 – but incorrectly. Zinnia elegans is the species from which our familiar garden zinnias were developed.

From 1796, seeds of Zinnia elegans were sent from Madrid to several amateur botanists in Britain – for example, Lady Bute (who also planted those new-fangled dahlias in her garden) and Captain Emperor John Alexander Woodford. In the Captain’s garden in Vauxhall, Zinnia elegans flowered successfully by 1799. From around 1800, zinnias slowly became more popular. By 1842, seeds of Zinnia elegans were available in every seed shop.

Zinnia – a common plant of the Regency period?

Zinnias were well known in the Regency period. Not every garden had them, but well-to-do gardeners cultivated them. There is little doubt that polite English society was aware of zinnias – whether through botanical books, the gardens of friends, or the artwork of Mary Delany. In general, botany became popular in the 1780s and 1790s, especially among middle- and upper-class women. Introductory books, newspaper articles, public and private lectures, and herbaria fuelled an enthusiasm for collecting and naming the world of flowers.

Would Jane Austen have enjoyed the colourful blossoms of the zinnia? We can only guess. I checked the library of Godmersham Park, to which Jane Austen had access. It features several books on gardening and botany, but about half were published before 1759, and those published afterwards do not mention zinnias. Considering that many plant nurseries in and around London sold zinnias around 1800, it is likely that the plant flowered in some city gardens or parks in London and Bath. Thus, it is quite possible that she knew Zinnia elegans. However, zinnias were not yet the garden staple they are today.

Related articles

Sources

John Abercrombie, John, Thomas Mawe: Every man his own gardener. Being a new, and much more complete gardener’s kalendar than any one hitherto published, 1782 https://books.google.de/books?id=MVwXAAAAYAAJ

William Curtis: Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, 1792 https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_the-botanical-magazine-_curtis-william_1792_5/page/n19/mode/2up?view=theater

Robert Edmeades, J. Andrews: The Gentleman and Lady’s Gardener, Containing the Modern Method of Cultivating the Kitchen-garden, Flower-garden, and for Raising of Forest-trees. With a General Catalogue of Seeds, Plants, and Roots … To which is Added, a Catalogue of Bulbous-rooted Flowers and Their Prices, 1776 https://books.google.de/books/about/The_Gentleman_and_Lady_s_Gardener_Contai.html?id=1tdItFHTmdkC&redir_esc=y

Sarah Easterby-Smith: Botanical colleting in eighteenth-century London, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 34(4) (2017):279-297, https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/10023/17202/SES_Botanical_Collecting_AUTHOR_FINAL_VERSION_.pdf;jsessionid=035EF18143CC1E7C1467019E72C9CF08?sequence=1

Eric Grissell, “A History of Zinnias: Flower for the Ages”, Purdue University, 2020

Philip Miller: Figures of the most beautiful, useful, and uncommon plants described in The gardeners dictionary, exhibited on three hundred copper plates,… To which are added, their descriptions, Vol 1, 1760 https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_figures-of-the-most-beau_miller-philip_1760_1/page/n135/mode/2up

Michael Richter: „Zinnie“, at https://blumen-natur.de/zinnie/, 26. November 2019

Nathalie Vuillemin: A silent herbarium? Joseph de Jussieu’s botanical collections from South America (1735–1770), Archives of Natural History, Volume 52, Issue 1: https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/anh.2025.0968

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)