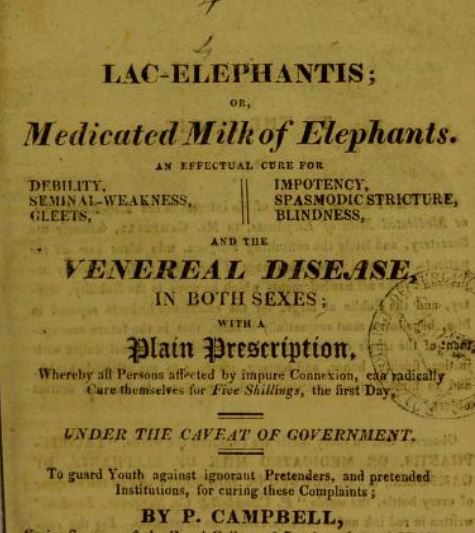

Around 1815, a cure against distressing, persistent or even untreatable illnesses caught the eyes of many patients on the brink of giving up hope. “Medicated Elephants’ Milk” promised help against nearly all physical evils: venereal diseases, gonorrhoea, noise in the ears, premature waste, blindness, and even grey hair and boldness.

The man behind the miracle was a certain Mr. P. Campbell, supposed Senior Surgeon of the Royal College of London. The medicine enjoyed considerable success.

But were things really as they seemed – or did Mr. Campbell’s genius lay in swindling?

A ‘miracle cure’ against nearly all physical evils

Mr P. Campbell sold Medicated Elephants’ Milk – or, more elegantly, Lac-Elephantis – from 29, Great Marlborough Street, London. His business flourished around 1812-1816. The medicine’s ingredient was, according to Mr. Campbell, genuine elephant milk. It was offered in bottles and also as pills for those unable to drink milk.

Clever medical marketing around 1815

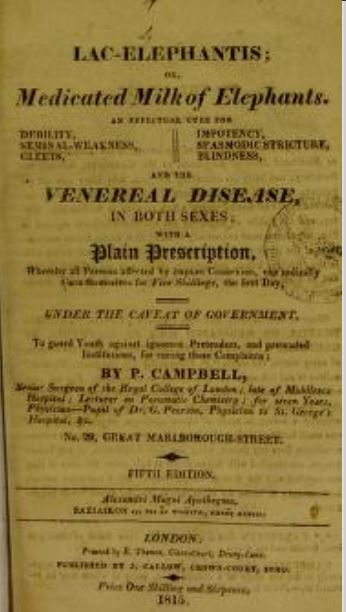

The center of his marketing campaign was a booklet called “Lac-elephantis; or Medicated Elephants’ Milk”.

It cost 1 shilling and sixpence and went through at least five editions.

The booklet was a perfect marketing tool, complete with testimonials, heavy name-dropping, exotic locations and a set of arguments to take wind out of the sails of the skeptics. The booklet also told the story of the author’s shining career as a doctor, with a scientific network and international patients of high rank (conveniently, the aristocratic clientele lived in far-away places such as Austria, Portugal or Russia, or had recently passed away).

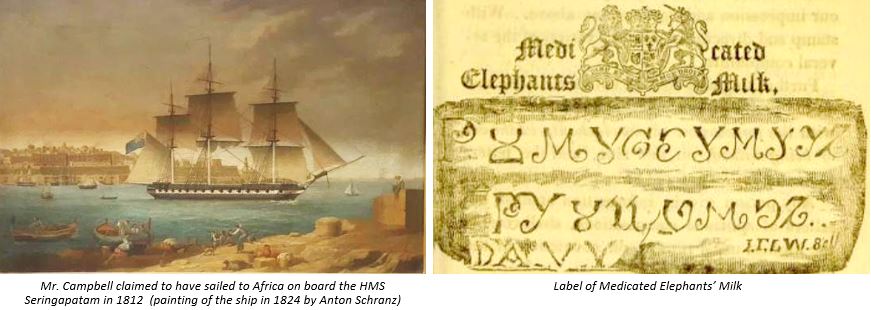

Mr Campbell took care to have his facts as correct as possible: When he claimed to have sailed to Africa in 1812 on board of the Seringapatam, a ship owned by Mr ‘Mellish’ and under orders of a Captain ‘Stivers’, then the ship as well as its route, the owner and the captain were real. Only the spelling of the names went wrong: correct were William Melish and Captain Stavers.

He also made sure to give extra credibility to Lac-elephantis by modestly declaiming that it was him who had invented the medicine. Rather, he had taken over from a Mr Davy (lost to obscurity today), after his “much lamented friend”, Mr Cavallo, told him about it on the death-bed.

Note the name-dropping here: Mr Cavallo refers to Tiberio Cavallo, an Italian physicist with special interest in electricity. He moved to Britain in 1771 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London. As Mr. Cavallo had passed away in 1809, Mr. Campbell was not in danger of being objected.

How to catch an elephant for milking

Campbell had a very fertile imagination. In his booklet, he described how female elephants could be captured to be milked:

The first step is to build a trap under a tree. Then, one frightens a group of elephants by noise, smoke and fire into panic, so that the animals take flight. The female elephant and its’ baby conveniently run for shelter to exactly the tree where the trap is set up. The animal could now be trapped and milked, and when it was released, it would return to its group in an instant, wrote Mr Campbell. The milk was than “prepared by our agents in Africa, in such a manner as to be capable of being kept for fifty years, in any climate.“

Dark clouds gather above Mr. Campbell’s head

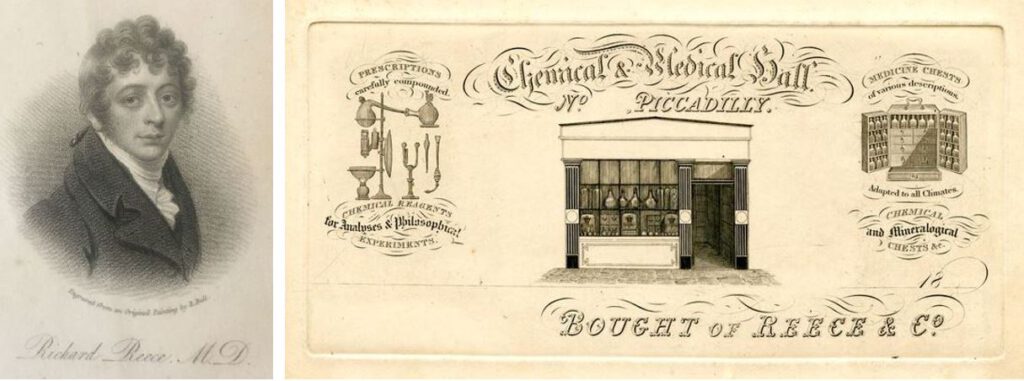

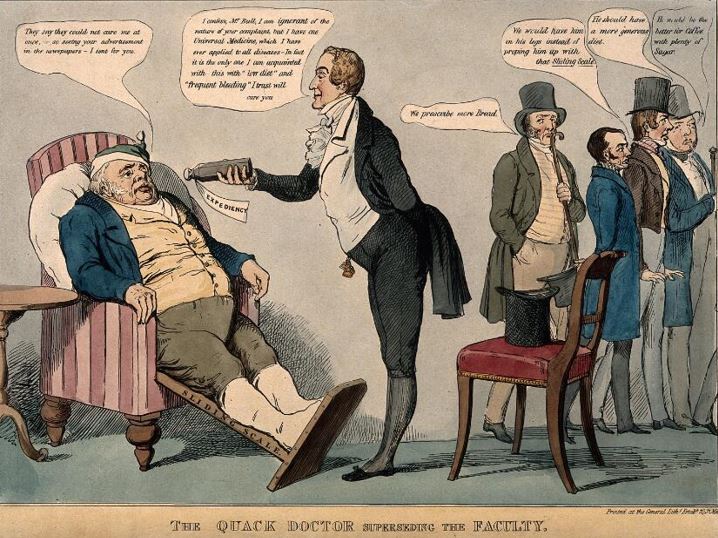

In 1817, book and miracle cure caught the eye of Dr. Richard Reece (1775-1831), a member of the Royal College of surgeons. Both objects made him raise his eyebrows. Lac-Elephantis sounded exactly like quackery to him. Thus, he had a closer look at it.

Dr. Reece was an opponent to reckon with. He had made himself a name as the tireless author on domestic medicine. He supervised the Chemical and Medical Hall that sold medicines and cabinet. And, most dangerous for Mr. Campbell, he ran the magazine The Monthly Gazette of Health.

Dr. Reece investigates

Reece publicly announced in his magazine that he would have the alleged miracle cure analysed. One month later, he published the result, heavily resorting to exclamation marks:

“On examining the contents of a ten-shilling bottle of Elephants’ milk, containing ten ounces, we find it to be composed of spirituous varnish (a solution of gum mastic in spirit of wine) six drachms, water nine ounces two drachms, on adding the varnish, the water becomes white, resembling milk!!! The ten shillings bottle costs the proprietor two pence. The concentrated milk is gum mastic and the doubly concentrated pills contain mercury!!!”

The next thing he tore to shreds was Mr Campbells professional career:

“We regret that such a palpable deception should come from a person who has received any thing like a medical education. We would have every man live by his profession, but when a man falls on such a mean subterfuge to entrap the ignorant, he sinks into greatest contempt. (…) For the honour of regular surgeons, we are happy in having in our power to state that the proprietor of Elephants’ Milk is not a member of the college of London. “

The doctors’ fight

The next thing that he tore to shreds was Mr Campbells professional career:

“You are a most infamous fellow, and only shews your total ignorance of all medicine by making such honourable mention of my Elephants’ Milk in your dastardly and ill-written pamphle. Ly on ignoramus. Each 10s bote coste me 7s 6d. each. Not so good a profit as your’s 11¾d out of every shilling.”

Dr. Reece did not hesitate to publish the letter in The Monthly Gazette of Health. He commented:

“We are sorry that the learned gentleman cannot point out any other error in our statement than that of the price. – Our analysis of his pretended milk is correct, and we defy him or any chemist to prove it otherwise; we therefore repeat that the original cost of the contents of a ten-shilling bottle does not exceed four-pence. If the article is not what the learned doctor represents it to be, viz. the milk of an elephant, the public will not hesitate to pronounce it an imposition.”

Mr Campbell: a charlatan, a surgeon, and a secret

Today, it is difficult to track down information about Mr Campbell. Lac-Elephantis is what he is remembered for. His first name seems to be lost in history, and there are no paintings of him. Even his address remains a mystery: While he himself claims to sell his medicine in 29, Great Marlborough Street, London, it is not sure if he did so: The same address is claimed by The Shakespeare’s Head. The pubs still existing today and states to have been at this address since 1735. Or does this mean that Mr. Campbell operated from a pub?

At least we know that Mr Campbell indeed worked in the medical field: He was part of the Royal Jennerian and London Vaccine Institutions’ inoculation team against the small pox around 1816. However, Mr. Campbell’s selling of Lac Elephantis gave the inoculation campaign a bad name. Vaccination activists such as the surgeon John Ring called for banning quacks from being part of the inoculation team.

After the exposure of the fraud, it is unclear what happened to Lac-Elephantis and its proprietor. Did Mr Campbell give up? Was he prosecuted? Did he continue selling his fraudulent medicine? We don’t know. His traces disappear in 1817.

Related articles

Sources

Dr. Richard Reece: The Monthly Gazette of Health, or; popular medical, dietetic and General Philosophical journal. VOL. II, from December 1816 – December 1817, 1. Edition, London

P. Campbell: Lac-elephantis, or, medicated milk of elephants: an effectual cure for debility, seminal-weakness, gleets, impotency, spasmodic stricture, blindness, and the venereal disease, in both sexes: with a plain prescription, whereby all persons affected by impure connexion, can radically cure themselves for five shillings, the first day: under the caveat of government, to guard youth against ignorant pretenders, and pretended institutions, for curing these complaints; 5. edition, 1815

John Ring: A Caution Against Vaccine Swindlers, and Impostors, 1816

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Reece, Richard

The Wellcome Collection, London

The British Museum, London

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)