Fans are so much more than fashionable accessories: They are useful for flirting, can cool heated cheeks or hide an unladylike emotion. In the wake of the Napoleonic War, their usefulness was boosted beyond the known limit when fans were made for spying, i.e. discretely observing the surrounding or other persons. I found some examples of these extraordinary devices when I visited the exhibition “Waterloo: Life & Times” of the Fan Museum in Greenwich, UK.

Fans are so much more than fashionable accessories: They are useful for flirting, can cool heated cheeks or hide an unladylike emotion. In the wake of the Napoleonic War, their usefulness was boosted beyond the known limit when fans were made for spying, i.e. discretely observing the surrounding or other persons. I found some examples of these extraordinary devices when I visited the exhibition “Waterloo: Life & Times” of the Fan Museum in Greenwich, UK.

There were two versions of the “spy fan” around 1800: a high-tech version and a low-tech version.

The Peeping Fan

The low-tech spy fan was the so called Peeping Fan. Small holes were cut in alternate leafs of the fan and adorned with sequins. For discretion as well as stability, the holes were filled with tender net or lace. The spy holes allowed a lady to have a discrete look at what’s going on around while covering her face.

The low-tech spy fan was the so called Peeping Fan. Small holes were cut in alternate leafs of the fan and adorned with sequins. For discretion as well as stability, the holes were filled with tender net or lace. The spy holes allowed a lady to have a discrete look at what’s going on around while covering her face.

A Peeping Fan is inspiring for Regency Novel Writers and breeds plot-bunnies: Such a fan comes in handy when the heroine, an aristocratic lady, wants to hide her face from the vulgar curiosity of the mob, but at the same time needs to keep an eye on the situation. Or would a young lady in the opera box discretely look out for her secret fiancé from behind the Peeping Fan?

The Monocular Fan

The high-tech “spy fan” mixed fashion with the latest scientific progress. For fans, the shape of a cockade became fashionable around 1800. The cockade fan was turned into a “spy fan” by adding a miniature spy-glass (see photo on the left). Such fans were referred to as “monocular fans” . The spy-glass was small, but its lens was efficient. Usually the spy-glass was fixed into the rivet of a cockade fan. A cockade fan allows you to peep through the spy-glass rather discreetly, as the device is in the centre of the fan and not at its head.

The high-tech “spy fan” mixed fashion with the latest scientific progress. For fans, the shape of a cockade became fashionable around 1800. The cockade fan was turned into a “spy fan” by adding a miniature spy-glass (see photo on the left). Such fans were referred to as “monocular fans” . The spy-glass was small, but its lens was efficient. Usually the spy-glass was fixed into the rivet of a cockade fan. A cockade fan allows you to peep through the spy-glass rather discreetly, as the device is in the centre of the fan and not at its head.

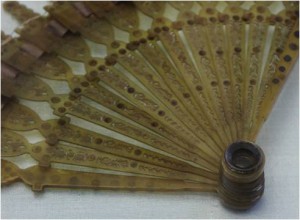

Occasionally, brisé fans were furnished with a spy-glass. This beautiful fan (photo on the right) was made in Switzerland. The spy-glass in the rivet fits so well into the elegant design that you hardly notice it. The fan is made of pierced horn and is painted with miniature scenes of rural life. It is an idyllic design for a seemingly innocent “lady spy.” In a Regency Novel, would the heroine use this brisé fan for observing eligible bachelors at a ball in a country house? Or is she a French spy at the English seaside, secretly spying at English war ships at the harbour?

Occasionally, brisé fans were furnished with a spy-glass. This beautiful fan (photo on the right) was made in Switzerland. The spy-glass in the rivet fits so well into the elegant design that you hardly notice it. The fan is made of pierced horn and is painted with miniature scenes of rural life. It is an idyllic design for a seemingly innocent “lady spy.” In a Regency Novel, would the heroine use this brisé fan for observing eligible bachelors at a ball in a country house? Or is she a French spy at the English seaside, secretly spying at English war ships at the harbour?

The photo on the left (click to enlarge) offers a closer look at the spy-glass. It is fixed into the rivet of a French horn brisé fan made around 1805. The sticks are shaped like classical urns – a rather morbid design. The spy-glass is bigger than the one of the Swiss fan (above), but disguised by being of the same colour as the horn sticks.

The photo on the left (click to enlarge) offers a closer look at the spy-glass. It is fixed into the rivet of a French horn brisé fan made around 1805. The sticks are shaped like classical urns – a rather morbid design. The spy-glass is bigger than the one of the Swiss fan (above), but disguised by being of the same colour as the horn sticks.

Why Fashion and Science Could Meet

Spy-glasses were developed in the 17th century. Their quality improved in 1733 with the invention of the achromatic lens. Achromatic lenses were expensive, and they were patented. The patent was held by the optician John Dollond. When his patent expired in 1772, prices for lenses dropped by half. Mass production and the development of “fashionable scientific toys” could begin. High society was fascinated with miniature spy-glasses. Spy-glasses were built in accessories for men (snuff boxes) and women (fans) alike.

Sources

The Fan Museum, 12 Crooms Hill, London SE10 8ER, UK. https://www.thefanmuseum.org.uk/

The exhibition “Waterloo: Life & Times” is held from 27th January – 10th May 2015.

Maurice Daumas: Scientific Instruments of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries; Praeger Publishers, 1972

Article by Anna M. Thane, author of the novel

“Von tadellosem Ruf” (http://amzn.to/2TXvrez)