- Poetry by Chiyo Kitahara

- Interview with the artist

- Additional information: Links to the Romantic Age

The Museum of Creativity is very proud to present poetry by the Japanese poetess Chiyo Kitahara, winner of the annual 67. Mr. H. award.

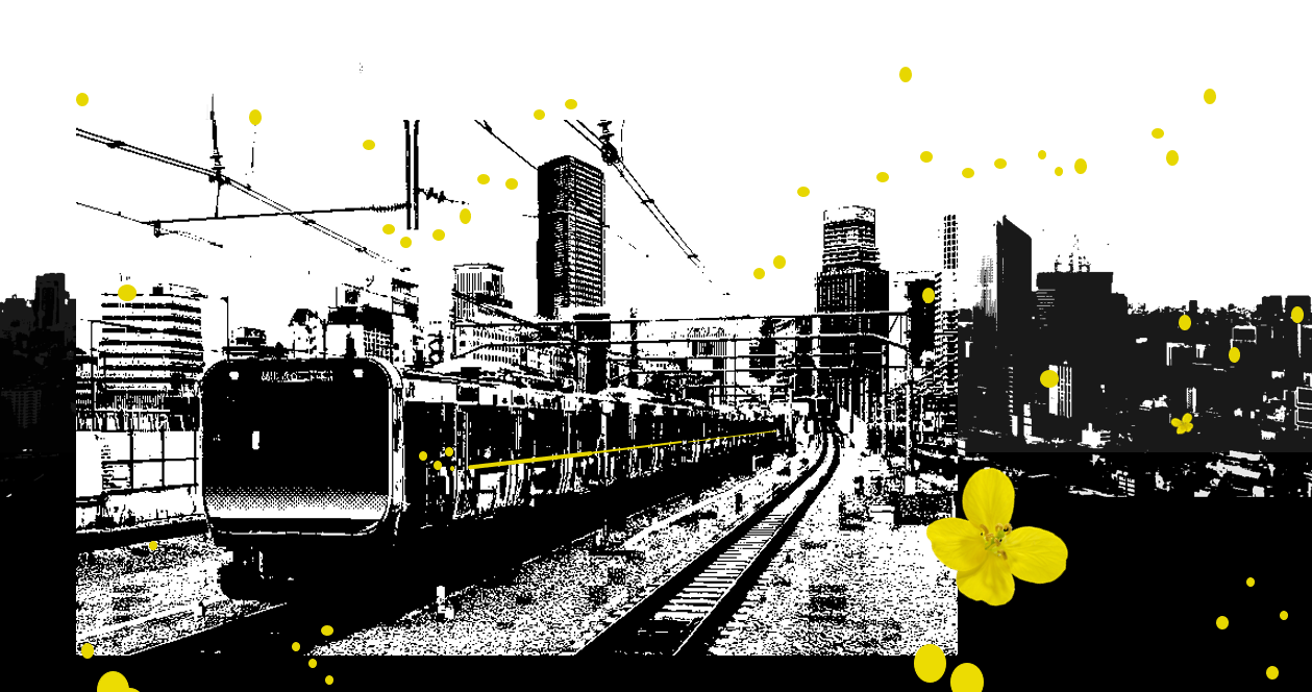

Ms Kitahara published her first poetry book in 2005. Its Japanese title means “While waiting for the local train”. Since then, she has published three further books and a private series of periodicals. The exhibition “Modern Japanese Poetry – poems by Chiyo Kitahara” on Regency Explorer brings English translations of her poems to the internet for the first time.

In my interviews with Chiyo Kitahara (below and also here), we talk about influences on her writing, cross cultural experience and a poet’s work.

Poetry by Chiyo Kitahara

The Keyhole

Destruction may be the result – A silver key

Put to a dark placeOn insertion – Deep inside – Softly

Something crumbledEnter

Said a voiceTumbling down

A staircase of atonal musicThe discarded key – Or perhaps

Me falling asleepRound the nape of a peacock’s neck – Arms entwine

Longingly – Scenting a fragrance for the first time

Face up – I think I may well bloom

(Translation by Michael Huissen)

Playful wind

The wind

stretches out it’s claws

tears the surface of the sea

hoicks it upThe waves tremble

while the wind

wheezes, baring its lips

and rushes through themFor being trapped in a standpost

in a puddle

limited by daily routine and pus

the wind does not likeAt a place suffused with light

the wind plays

with a one year old

gentle white heron

(Translation by Anna M. Thane)

Parting, coming from a distance

In the morning haze having ladled water at the spring and

Embracing the jar returned to the hut at the lynchet

The water sinks glisteningly and rises

In the jar made of white clayA crack within happiness

The calm chant

Is crossed by the dark needle of forebodingUnable to avert it

Returning half of the water to the groundThe sound of hobnailed boots approaching

Shuddering eyes wide open

Still embracing the jarComing out of the haze

Soon we will meet and then appears

The cap without the face of the person gone(Translation by Anna M. Thane)

New book published in 2022!

Chiyo Kitahara published her fifth book, “Yoshiro, Katsuki, Nami, and Urara” in 2022. The book was created with the feeling of mailing a letter to a close friend. It features small story-like poems: Memories of her stay in Germany when she was young, the days she took care of her parents, and the “truth of the trembling of her soul”.

Here is my translation of one of the central poems of the book, Hitohira no:

A petal’s

butterfly!

The yellow of petals!

Who the heck are they getting this call from?

From the house at the oilseed field to the city where the trains run

I wonder how many petals – singles and couples – are flying to the cityLike a flood running down the stairs to the underground and up

Tepidly pollinating the windows of commuter trainsA station bench’s cold whiff from a drift

A stranger with a book spread open

You’re grown enough

Please let me know if it is written thereOn the way to emergence

the time when you are about to change from light-green to yellow

in the yard I was present when someone was about to be born, but

I got scared and fled.

(Translation by Anna M. Thane)

Chiyo Kitahara is now online: http://barairotm.exblog.jp/

Interview with the artist

Anna: Thank you for sharing your work with The Museum of Creativity. Can you tell us about your sources of inspiration?

Chiyo Kitahara: I like to think of my books as individual projects, and I want them different in style and topic. Each is based on or influenced by a different idea or concept. I don’t want to repeat a theme I have used already.

What ideas are your poetry books based on?

My first book, “While waiting for the local train”, was inspired by literary realism. I depicted activities and experiences of everyday life with regard to predestination and free decision.

The second book, “Spiritus”, is about life in the countryside. I looked closely at the place where I was raised and now live again. Inspiration probably came from the thoughts and writings of the Japanese poet Kenji Miyazawa. His writings show sensitivity for the land and for the people who live and work there.

The idea of genius loci is the guiding theme of my third book, ”Cocoon House”. Genius loci means “spirit of a place”, but is often used in an abstract way, referring to the atmosphere or impression of a place. I understand it in the literal sense. The book has therefore a mythological touch.

Since when have you been writing poetry?

I started writing poems at the age of 16. I contributed poems to a monthly student magazine and to literary circles of my high school and my university. However, when I was 20 years old, I gave up writing, because I focused on playing the piano for a ballet studio. I love music and ballet very much.

Is music still competing with your writing?

Today, I divide my time between playing the piano and writing. Besides poems, I also write essays and stage plays. I combine stage plays with classical music, such as pipe organ music at a concert hall. For example, I wrote a script titled “Dracula” for a Pipe Organ Suite. It is a stage drama and when it was performed, I took part as a narrator. Working for the stage really is fun.

Was brought you back to writing poetry?

I have never stopped writing poetry for long. But yes, there was a key moment in 2002. After having raised my children, I wrote a poem titled “Invitation Card”. I sent it to a local poetry competition – and it was awarded! I was very surprised that a small piece of poetry could touch other people’s heart directly. Since then I have been writing with dedication. I also recite my poems in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, and so on. I also started taking part in a series of solo performances called “La Voix des Poètes” in Tokyo in 2012. Since then, I have participated 6 times.

How do you write?

I believe that my works are already completed before I start writing, so I write as if I read a book – just as the Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg once said. I write on the computer, not by hand on paper. When I sit down and face my PC, fragments of a poem suddenly appear. I trace them carefully by using the keyboard.

Do you want to tell a message with your poetry?

I think art ceases to be art when in takes on a mission. It becomes a statement or even propaganda instead. As Hölderlin said, art is about aesthetics.

You lived in Europe for some time. Did this experience influence you?

I lived in the German city of Marburg from 1994 to 1995. When I returned to Japan, I suffered the reverse cultural shock. A question rose inside me: “Where does man come from, and where does he go to, and who determines that?” This question became the main theme of my first poetry book.

After returning to Japan, I attended some lectures about German literature at Kyoto University for two years. I studied German poets, especially Hölderlin.

Are there other influences on your writing?

Definitely. First of all, there is my father, Kazunori Echigo. He is a retired professor and a doctor of economics. He studied in Scotland in the 1960s. When he came back to Japan, he brought with him a record and a book of Scottish folk songs. The lyrics were written by Robert Burns. I didn’t understand the text very well – being only about 10 years old at that time – but I really enjoyed the sound of the words. This was my first happy experience with foreign poetry.

At about the same time, I read some poems by the Japanese poet Kenji Miyazawa. I was deeply impressed by his beautiful Japanese and also by his touching stories.

Do your readers influence you?

Yes, indeed. After publishing my first poetry book in 2005, I received many letters from readers. One of the most impressive ones was by Professor Yoshikatsu Kawanago. He is both a poet and an outstanding expert on Johann Georg Hamann, a German philosopher. I like Hamann’s thoughts about language: He did not consider language a passive system of signs for communication. He believed poetry to be the mother-tongue of the human race. As a poet, how could I disagree?

Also from a letter of a reader, I got to know Emily Dickinson’s work better. Before, I had only known her name. I have been reading Emily Dickinson’s poems intently since then.

What are your plans for the future?

I plan to publish the forth poetry book and am currently preparing for that. I also would like to publish my first essay, dedicated to Atsuko Suga, a multicultural writer and leading translator of Japanese literature into Italian. Ms Suga went to Europe in the 1950s for her studies. One of her main ideas was that intercultural barriers can be overcome by respect for cultural identities and acknowledgement of differences. She was very open-minded about different cultures and mind-sets.

Another essential topic for Ms Suga was “religion and literature”. Shortly before she died, she confessed that what she really had wanted to write about was religion, literature and the conflict she saw between them. Ms Suga deeply believed and trusted in the mutual understanding between people, without regard to race, religion or age. I have the greatest respect for her and her universal work. I would like to take over from her if I could. My essay on her will appear in my private periodical “Bara-iro-tsume” – “Rose-coloured Claw” in English.

How long have you been publishing “Bara-iro-tsume”?

I started “Bara-iro-tsume” in 2010, so I can keep in contact with my readers. It is published twice a year and I sent to my readers. I have been adding pictures by an artist since volume 5. Some of them are currently on display in your Museum of Creativity.

Do you have a favourite poet?

There is Hakushu Kitahara, one of the most popular and important poets in modern Japanese literature. He wrote so-called tanka. A tanka is traditionally a short poem consisting of five lines, usually with a fixed number of syllables. The standard pattern is 5-7-5-7-7. Hakushu Kitahara’s rich imagery and innovative structure were significant for the development of modern Japanese poetry. My pen name Kitahara comes from him.

I like the poems of Rose Ausländer. Among of my favourite poems are “Als gäbe es“ (“As if there were”) and “Gib mir” (“Give me”).

By Emily Dickinson, I especially like “This is my letter to the world”, and “Because I could not stop for the death!”

Finally, Reiner Maria Rilke is among my favourite poets. His poetry helped me when I was writing my third book. There is also a pleasant memory connected with him: After publishing my third book, a poet whom I admire gave a comment on it to a newspaper. She pointed out that one of my poems, “The Keyhole”, reminded her of Rilke’s “Das Rosen-Innere” (“The Interior of a Rose”). I was very amazed and honoured.

Visit Chiyo Kitahara’s blog at: http://barairotm.exblog.jp/

Publications by Chiyo Kitahara

- “Lokaru ressha-wo matchinagara” (“While waiting for the local train”), Doyo-bijyutsu-sha Publishing Co., Tokyo; 2005

- “Supiritousu” (“Spiritus“), Doyo-Bijyutsu-sha Publishing Co., Tokyo; 2007 (nominated for the Mr. H. Award1))

- “Mayu no ie” (“Cocoon house”), Shicho-sha Publishing Co., Tokyo; 2011 (nominated for the Mr. H. Award)

“Bara-iro-Tsume” (“Rose-coloured Claw”), Private edition, since 2010. - “Shinshugawa – Barroco“, Shicho-sha Publishing Co., Tokyo, 2016 – winner of the 67. Mr. H. award

Chiyo Kitahara is a member of

- Japan Poets Association

- Japan Poets Club

- Japan Universal Poets Association

1) The Mr. H. Award is a Japanese award in recognition of an outstanding anthology of poetry published by a new poet.

Additional information: Links to the Romantic Age

When I established the Museum of Creativity, I did not expect its exhibitions to have any link to the Regency era or the Romantic age at all. It turned out to be quite different: The Photography Project “Spring butterflies” was inspired by the silhouette style of the early 19th century. The Japanese Poetess Chiyo Kitahara counts a German poet of the romanticism, Friedrich Hölderlin, to the influences on her work. In my interview with her, it also turns out that Ms. Kitahara is familiar with the work of the philosopher Johann Georg Hamann. I have compiled some information for you on Friedrich Hölderlin and Johann Georg Hamann:

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843)

Hölderlin’s poems are today recognized as one of the highlights of German poetry. They were little known or understood during his lifetime, though.

Even if was he not understood by his contemporaries, Hölderlin was a typical example of a poet of the Romantic age: He was an early supporter of the French Revolution, and in his youth an enthusiastic admirer of Napoleon (see below an attempt to translate Hölderlin’s poems about Napoleon into English).

Young Hölderlin was rather revolutionary: As a student of theology in Tübingen, he and his friends G. W. F. Hegel and F. W. J. Schelling planted a “liberty tree” on a meadow near the seminary, much to the displeasure of the Grand-Duke of Württemberg, who had this “alleged democratism” investigated.*

Hölderlin was a fervent admirer of ancient Greek culture. His hymn-like style was based on a genuine belief in the divinity, and he often fused Greek mythic figures, the Pietism of his native Swabia and romantic nature mysticism. In the great poems of his maturity, Hölderlin would generally adopt a large-scale, expansive and unrhymed style. Some of his later poems are fragmentary, but have astonishing intensity. Hölderlin seems to have considered the fragments, even with gaps and unfinished lines and incomplete sentence-structure, to be poems in themselves.

This is my translation of Friedrich Hölderlin’s poem on Napoloen, written in 1797:

Buonaparte

Sacred vessels poets are

Wherein life’s wine, the spirit

Of heroes, remainsBut the spirit of this youth,

So bold, will it not burst

The vessel, where it meant to capture it?The poet shall leave it untouched like nature’s spirit

Such matter turns the master into the apprenticeIt cannot live nor stay in poems,

It lives and stays in the world.

Read Friedrich Hölderlin’s poems online in German: http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/262/83

Johann Georg Hamann (1730 –1788)

Johann Georg Hamann, a noted German philosopher, influenced many poets and thinkers of the Romantic age. In the past, he was commonly thought to be a proponent of the Counter-Enlightenment. However, today’s experts such as professor Yoshikatsu Kawanago** points out that Hamann was not against Enlightenment at all:

It is true that Hamann criticised the rationalism of his time, and some of his contemporaries took this as proof that Hamann was the archenemy of the Enlightenment. However, to criticize something does not necessarily mean to oppose it.

Immanuel Kant famously defined Enlightenment as man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Hamann disagreed with this. By this definition, he argued, Kant did not show any kindness towards the persons “charged” with self-imposed immaturity. Kant rather acted as their guardian, denying any collective challenge with the so-called immature and escaping to “august intellectual worlds”.

Thus, Hamann did not criticise the emancipative process of the Enlightenment. What he criticized was the arrogant attitude of the Enlighteners. Therefore, Hamann’s work is today interpreted as a meta-criticism of the Enlightenment, a form of self-criticism. Hamann is regarded as the advocate of unbiased rationality against a dogmatic rationalist faith.

This new view on Hamann is the result of research on his work in the second half of the 20th century, when Hamann’s letters and scripts, including those unpublished in his lifetime, were published.***

Hamann’s most notable contributions to philosophy were his thoughts on language. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains, Hamann championed the priority which expression and communication, passion and symbol possess over abstraction, analysis and logic in matters of language. Symbolism, imagery, metaphor have primacy. To think that language was essentially a passive system of signs for communicating thoughts would deal a deathblow to true language. Consequently Hamann believed poetry to be the mother-tongue of the human race. However, Hamann did not equate language with emotional expression. Language has a mediating relationship between our reflection and our world. ****

His own style of writing was based on the “sentience” of the writer’s existence and was extremely allegorical. He employed an abundance of imagery. This imagery was free of theological traditions. Hamann even combined biblical imagery and pagan mythology. He also created new imagery by combining quotes that had no cultural similarity to each other. Thus, his writing seemed to be dark and abstruse (“sibylic”, as Goethe called it). Hamann’s writing was meant to cause amazement among his readers, by which he entered their hearts.

Hamann’s challenging style is believed to be an important part of his hermeneutics. Yoshikatsu Kawanago explains that Hamann redefined the roles of writer, critic and reader. He did so with the imagery of the “universal priesthood of all believers”: The writer serves the reader as the preacher does the laity. The critic is depicted as a kind of “bishop” interpreting the meaning of a text to the reader. He becomes redundant in Hamann’s understanding. The reader, so far passive, can now be active and is asked to reconstruct the meaning of a text himself.***

Notes and sources

* http://www.wbenjamin.org/hoelderlin_chron.html

** Professor for German language, philosophy and cultural anthropology at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo. Read more about his studies here.

*** http://www004.upp.so-net.ne.jp/kawanago/KRIBEW.HTM