In this post:

The traditional making of watercolour-paper

Watercolour-painting’s Golden Age

Technical innovations at the service of art

How to use making watercolour-paper or watercolouring in your Regency Novel

The pleasant village of Roadwater lies a couple of miles behind us, and the small road leads into a forest. We are on a field research trip to Two Rivers Paper Mill in Somerset/UK to learn about the traditional production of watercolour paper. Exploring the Regency period can be exciting – and might include loosing the way. We are about to turn the car, when we see a white building with a black slate roof. It is Two Rivers Paper Mill, built in the 1680ies. In the Georgian era, the mill was a thriving corn mill, known as Pitt Mill. Today, the mill is a centre of the traditional production of a paper that was vital for the latest trend in arts during the Romantic Age: high-quality watercolour-paper.

The pleasant village of Roadwater lies a couple of miles behind us, and the small road leads into a forest. We are on a field research trip to Two Rivers Paper Mill in Somerset/UK to learn about the traditional production of watercolour paper. Exploring the Regency period can be exciting – and might include loosing the way. We are about to turn the car, when we see a white building with a black slate roof. It is Two Rivers Paper Mill, built in the 1680ies. In the Georgian era, the mill was a thriving corn mill, known as Pitt Mill. Today, the mill is a centre of the traditional production of a paper that was vital for the latest trend in arts during the Romantic Age: high-quality watercolour-paper.

Jim Patterson, the enthusiastic and congenial owner of the mill, greets us at the garden gate. He exhibits the air and energy of a rock star in spite of his approaching the age of 70. Jim is passionate about paper. Together with his colleague Neil Hopkins he produces high-quality watercolour-paper for artists. Jim has spent all his working life in the paper industry. He was heavily involved in developing the Paper Trail’s Frogmore Paper Mill & Visitor Centre near Hemel Hempstead and is perfectly acquainted with the historical Fourdrinier paper machine. Besides making paper, he gives talks, and visitors are welcome to the mill during regular working hours (best to call in advance, though). This is my chance to get an insight into watercolour-paper making as it was done in the Romantic Age – or nearly so: Some minor electric devices have crept in.

Jim takes us to the old metal water wheel outside of the mill. The wheel is 100 years old, but still functioning. Jim bought it in Wales when he set out to restore Pitt Mill in the 1980ies. He then ushers us inside. The ceilings are low, with massive wooden beams. A steep and narrow wooden stair leads up to the first floor, and further to the loft. On the ground floor, the mill retains much of the ancient wooden milling machinery.

Jim takes us to the old metal water wheel outside of the mill. The wheel is 100 years old, but still functioning. Jim bought it in Wales when he set out to restore Pitt Mill in the 1980ies. He then ushers us inside. The ceilings are low, with massive wooden beams. A steep and narrow wooden stair leads up to the first floor, and further to the loft. On the ground floor, the mill retains much of the ancient wooden milling machinery.

We meet Neil Hopkins, Jim’s colleague and friend who has been making watercolour-paper for 12 years. He is busy making a limited edition of special paper for an advertising company: Flakes of copper foil have been added to the pulp for a glamorous effect on the paper.

Besides making high-quality watercolour-paper for artists, Jim and Neil make and design paper to order for special occasions: Then coffee, flowers, jeans fibres or other material can be added to the pulp. As far as I know, Jim and Neil are the only persons in England ready to take on such a job professionally with traditional machineries. The mill is the last resort in England for this old craft, and they would accept lot sizes as low as about 50. So if you are looking to get your own bespoke paper, Two Rivers Paper Mill is the place for you.

The traditional making of watercolour-paper

Jim shows us how to make watercolour-paper in the traditional way. I have documented the process for you. Click here to go to a short photo story about this craft..

High-quality watercolour-paper was in high demand by watercolour-artists in the Romantic Age. They would have walked from mill to mill looking for the best watercolour paper. Why so?

Watercolour-painting’s Golden Age

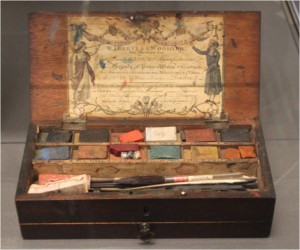

The years from 1750 to 1850 are the so-called Golden Age of watercolour-painting in Britain. The trend started with artists tinting topographical drawings in graphite or ink, using a limited range of pale colours. Then they began to experiment with more and stronger colours, a freer use of brushwork and rough-textured paper. The ideal was to capture fleeting atmospheric effects. Artists such as Paul Sandby, Joseph Mallord William Turner, John Girtin, John Sell Cotman and David Cox revolutionised the art of watercolour-painting and made it fashionable. Promoted by exhibitions and developed in Watercolour Societies, watercolour-painting became an accepted art. Amateur artists joined in, and young ladies of good breed soon were expected to be accomplished in watercolour painting.

The years from 1750 to 1850 are the so-called Golden Age of watercolour-painting in Britain. The trend started with artists tinting topographical drawings in graphite or ink, using a limited range of pale colours. Then they began to experiment with more and stronger colours, a freer use of brushwork and rough-textured paper. The ideal was to capture fleeting atmospheric effects. Artists such as Paul Sandby, Joseph Mallord William Turner, John Girtin, John Sell Cotman and David Cox revolutionised the art of watercolour-painting and made it fashionable. Promoted by exhibitions and developed in Watercolour Societies, watercolour-painting became an accepted art. Amateur artists joined in, and young ladies of good breed soon were expected to be accomplished in watercolour painting.

Technical innovations at the service of art

Watercolour paintings wouldn’t have become first-class pieces of art without the improvements in making watercolour paper. Prior to these improvements, the paper hadn’t been ideal for watercolouring, for it was often uneven, had a weak texture or a surface that was disturbed by impressions of the mould’s wires.

Improvements in the process of paper production were crucial to drive watercolour-painting to new heights:

- In former times paper was made of cotton rags that were beaten to pulp in water. For centuries the beating had been done with stampers, but these were replaced by the so called Holland beater. Using the Holland beater resulted in shorter, smoother fibres and thus in a more refined pulp. From that, smooth and even sheets could be made. The Holland beater had been invented in Holland before 1670 and was used in paper mills in other European countries by the middle of the 18th century.

- The pulp became even smoother when the “knotter” came into general use around 1819. The knotter removed clumps and unwanted substances from the pulp.

- To form a sheet of paper, the pulp was gathered in moulds. These used to have parallel laid wire lines. When the pulp was pressed and dried to paper, it retained the parallel wire lines. As a result, wet watercolour uncontrollably pooled along these lines. To avoid such disruptions, a new mould was invented around 1757 by James Whatman the Older: a mould with a fine wire-mesh that left no impression on the paper. The paper made in the new moulds was called wove paper. It allowed watercolourists to apply precise washes of watercolour.

- By the 1780s, James Whatman the Younger had developed a wove paper ready-sized with gelatine. Such a protective coating allowed the watercolourists rewetting and reworking a painting without causing damage to the paper.

It is amazing how technical improvements were driving change in the Romantic Age. I am glad I could learn more about it at first hand from Jim and Neil at Two River Paper Mill. They took the time to show us around and their passion for the traditional craft is just inspiring. We bought some sheets of watercolour-paper – now we have to see if I turn out to be an accomplished watercolourist.

How to use the craft of making watercolour-paper or watercolouring in your Regency Novel

If you have become inspired by the traditional craft of making watercolour paper, why not use it in your Regency Novel? Plot-bunnies are easily bred from it:

- If your heroine is an accomplished watercolourist, her high-born admirer, a dandy, literarily can go miles to purchase the perfect watercolour-paper as a gift for her, venturing deep into the countryside where he has to cope with “normal” people and mud on his boots.

- Maybe your hero is a patron of the arts. He discovers that the daughter of a paper maker is very gifted with pencil and colours. He takes the girl to London and has her educated by leading artists of the day. Throw in a little bit of “Pygmalion”, if you like, and don’t forget a love-affair, jealousy and the happy ending between patron and protégée.

- Or is a paper maker secretly in the service of the French, smuggling secret messages out of the country via watermarks in seemingly harmless watercolour-paper?

Related Topics:

- “Kiss” or “Smack” – Print Your Personal Letterhead Using the Techniques of the 19th Century

- Travelling with Turner: Exploring the Swiss Alps in 1802

- A Writer’s Travel Guide to London’s Bookbinding Trade

- New Shades of Blue Discovered in the 18th Century

Sources

Two Rivers Paper Mill, Roadwater, Somerset

http://www.tworiverspaper.co/themill.html

Elizabeth E. Barker, Department of Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bwtr/hd_bwtr.htm

http://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v15/bp15-21.html

http://baph.org.uk/ukpaperhistory.html